Boy, this list is late this year, huh? Well, first of all, I’d like to completely shirk any personal responsibility by complaining about how 2024 was a year featuring three (yes, 3!) 100+ hour RPGs that I ended up playing through. Kind of like complaining about just how great the weather is in the Bahamas, but alas. It’s not every year you have a backlog like that — actually, I’ve never had a backlog like that. So yeah, it took me a long time to get to most of the stuff I wanted to in order to assemble this list.

2024 was a strange year in that sense. It was a slow-ish year, coming down off the high that was 2023’s release calendar, albeit with some especially heavy hitters. Definitely lopsided for sure, but a year that had some truly incredible stuff that I won’t soon forget.

All that said, let’s get into my personal favorite games of the year.

Real quick, a couple disclaimers –

Quick obligatory notes:

- This is a ranked Top 10 list with 3 honorable mentions (unranked).

- Each game features a link to one of my favorite pieces of music from its soundtrack or to a clip of the game. Feel free to listen as you read.

- I consider the release timing of Early Access games based on when they exit Early Access, or enter V1.0.

- Remakes (which are becoming even more common these days) can be on my lists, but only if they are substantial enough in that the game is something fundamentally different. Examples of games I counted in 2019 were Pathologic 2 or Resident Evil 2. In 2020, I didn’t consider a game like Demon’s Souls (even though I loved it) because it is mostly a visual overhaul to the 2009 original game. Hopefully that distinction makes sense and isn’t just arbitrary to you.

Pile of Shame (games I didn’t have time to play):

- Astro Bot

- Helldivers 2 (I played this one, but not enough to have a fully formed opinion on it – sorry!)

- Hellblade: Senua’s Saga

- Factorio: Spae Age

Okay, with that out of the way, on to the list…

Honorable Mentions:

The Outlast Trials – Red Barrels

Hey, that’s my bad, y’all. I was just looking for the little boys’ room.

Let the Trials Begin – Tom Salta

When was the last time you played a mandatory tutorial level for a multiplayer game where you thought to yourself holy shit this is cool? For me, it was when starting The Outlast Trials for the first time. As a friend and I sat down to play together, we groaned at the idea of needing to finish a forced singleplayer level before we could get in a lobby together — that was, until we got into the thick of it. As we progressed through the fucked up house of horrors that kicks off the game, each at different intervals (his game had finished installing before mine), we kept yelling into our mics, our Discord user icons lighting up with each of us trading “holy fucks” back and forth. It was legitimately terrifying, and got us into the Halloween Spirit, big time.

Congratulating a game on a tutorial level might seem like a pretty backhanded compliment, but I’m being totally sincere. The fact that a sequence like that was so good when it didn’t have to be speaks to the level of care the team at Red Barrels has poured into practically every inch of this game. No detail is too small to be obsessed over. Just walk around the game’s elaborate multiplayer lobby, playing games of fully realized prison chess with your co-op partner, or enter a sensory bombardment chamber to participate in a Stroop Test together, breaking your brain while feeling like a lab rat.

Then there’s the core gameplay itself — a multiplayer PvE game with no combat, and very little options for fighting back. Part stealth game, part communal puzzle solving experience, and part group strategizing effort — I haven’t really played anything else like it. Not only that, but this is the rare multiplayer experience that remains scary in spite of everyone clowning around, throwing bottles like idiots and hiding in lockers right before the enemy enters the room. It’s all fun and games, until you’re the one the enemy is chasing around with a electric police baton.

The thing I like the most about the game, however, is its worldbuilding and vibe — The Outlast Trials takes the bits and pieces of lore established by the previous entries in the series and runs hog-wild with it, envisioning a savage version of the early 1960s where the most virulent, dogmatic tactics of anti-communism practiced by the US intelligence agencies were allowed to spin off into the dreaded morass of the private sector. The Murkoff Corporation — the Outlast series’ version of Umbrella Corp — is the kind of shadowy organization Allen Dulles would have been proud of. Imagine an alternate history where MKUltra had spawned an entirely new industry of human experimentation and supernatural research, the CIA had outsourced it to the highest bidder, and all the most extremist targets of Operation Paperclip were flown in to staff the place — and you’ve pretty got the ethos of Murkoff. The Outlast Trials walks a tightrope between conceivable, depraved reality and outlandish, over-the-top evil — the exact position where horror thrives.

The Outlast Trials is a horrifically unique game, hell bent on immersing you in total depravity. Give it a shot if you have some fellow sicko friends who fancy themselves horror aficionados; it’s worth experiencing its hellish world for yourself.

Crow Country – SFB Games

That art style is just *chef’s kiss*.

Fairytale Town – Ockeroid

Crow Country strikes the perfect balance between nostalgic trip down memory lane and invigorating original take on a classic genre. Its retro art style is immediately eye-catching — the low-poly art is impeccable, the CRT shader is so good that it’s like you’ve switched back to component cables — and yet, once you dig deeper, you’ll find it is more than just a pretty pixelated face. Its way of handling the camera is such a good idea that I can’t believe no one has tried it sooner — you can freely rotate it with the right stick, but the angle is so aggressively angled toward a top-down perspective that you still get some of the claustrophobic effect that old-school static camera angles provided. The left analog stick offers more modern movement, while the D-pad gives you access to good old tank controls — you know, for whenever you feel like playing the correct way.

The good ideas don’t stop there: Crow Country takes cues from southern gothic horror for its unique setting — an abandoned amusement park named for its owner, wealthy Atlanta land speculator Edward Crow. Not only are the vibes great — well, spooky — but it turns out that an abandoned amusement park makes for a great survival horror locale — each of the park’s different lands are visually distinct and easily navigable, while the various attractions make for an excellent narrative excuse to pack the place to the brim with intricate and off-the-wall puzzles. And, on top off all of that, the main character, Mara Forest, is everything you want from a horror protagonist — an unplaceable cocktail of wit, humor, eccentricity, and a not-so-clear backstory. Experiencing Crow Country’s wickedly smart puzzles with Mara’s musings to keep you company made for a great little survival horror package.

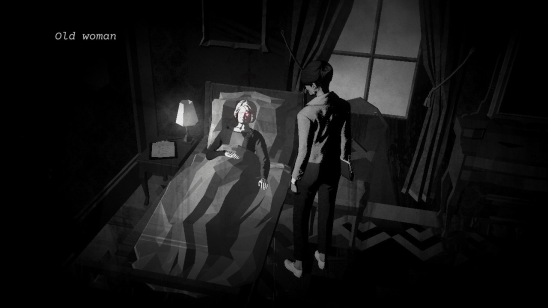

Indika – Odd-Meter

Indika is a blend of the mundane and the cosmically weird.

Joel – Mike Sabadash

I can all but guarantee, without even knowing who you are, dear reader, that you’ve never played a game quite like Indika. Equal parts experimental genre piece, interactive arthouse film, surreal Soviet-style comedy, and deeply personal crisis of faith, Indika is a fever-dream-with-a-heart-of-gold. You play as Indika herself, a nun in a Russian Orthodox convent who is shunned by her fellow Sisters in Christ, who believe her to be harboring the the voice of the devil. From the jump, everything in Indika’s world seems to be a contradiction. While she laboriously fetches 5 buckets of water from a well, there’s an always-visible point indicator at the top of the screen. After filling all 5 buckets worth of water, an elder nun spitefully pours it all out on the ground, at which point Indika “levels up”, rewarding her to pick a perk from a skill tree that only offers ways to increase her “Repentance”, “Grief”, or “Regret”. In the following scene, as Indika joins the other nuns in the chapel for prayer, she hallucinates a tiny, whimsically sized man, who jumps out of an elder nun’s mouth and begins dancing down the priest’s arms, grooving to what sounds to be late 90s era electronica.

In spite of how bizarre it is, Indika is a relatable story about a person harboring doubts about their faith in God. How can there be a just God when everything around us seems so random and devoid of meaning? The game’s core insight around a loss of faith is one that has stuck with me ever since I played it — Indika suggests that religion isn’t just about what you chose to believe in or philosophical quandaries about whether God does or does not, in fact, love you, but rather it is ultimately about how you see yourself and how you allow the world to see you. A religion that preaches original sin requires you to see yourself, first and foremost, as a sinner. What does a lifetime of thinking this way do to a person’s self-image? And how would it feel to suddenly be liberated from it?

For those interested in indie games with big ideas about life and the world, I can’t recommend Indika enough. It’s best to go into the experience as blind as possible, so I don’t plan on saying too much else — go experience it for yourself.

Top 10:

10. Frostpunk 2 – 11 Bit Studios

In the right lighting, this settlement looks kinda cozy.

The Great Old Enemy – Piotr Musial

For my money, Frostpunk 2 is a sequel in the truest sense of the word. Rather than overlaying new features atop the pre-existing base game — vertically scaling everything — 11 Bit Studios has opted for a different approach. They’ve scaled the game horizontally, widening the scope and increasing scale without intending to supplant the experience of playing the original. This is a sequel that lives alongside the original game — one where the gameplay experience of playing each part complement one another.

At its core, the original Frostpunk was a City Builder game centered around a massive coal-burning generator — your lone source of heat. You constructed your settlement in ever-widening concentric rings expanding outward from this lifeline. The experience was tense and intimate, starting with only a few dozen settlers. As you ordered your workers to begin mining coal, you’d watch them laboriously trudge through shoulder-high snowbanks toward the resource deposits. Even by the end of the main scenario, your population rarely exceeded a few hundred souls. And even though you often had to ask terrible things of your people, you really had the sense that you were in this fight for survival alongside them.

Frostpunk 2 does not attempt to recapture that same energy. Instead, the sequel is a bona fide 4X game — a la Civilization or Endless Legend — complete with multiple fully-fledged settlements to jump between, resource surplus and deficit statistics, trading systems, competing factions, and an entire governmental parliament for you to manage. The timescale of the game is no longer measured in days, but weeks. Your population is not measured in dozens or hundreds, but thousands. Unlike the original’s close-quarters management, you’ll spend considerable time zoomed out, juggling constantly competing priorities. What remains unchanged, however, is the palpable tension — Frostpunk 2 starts out overwhelming and only snowballs from there. It’s a game about the frantic struggle to keep numerous spinning plates from crashing down simultaneously.

Frostpunk 2 picks up roughly 30 years after the original. The once-tiny settlement of New London has exploded in size — its structures now spill outward over the crater walls that once confined it. Its population has grown exponentially — at the game’s onset, the city grapples with the food and shelter demands of 8,000 people. The unnamed captain who led the city during the events of the first game has just passed away, and leadership responsibilities now fall to you — a transitional figure known only as the Steward. As you assume control, beginning to “frostbreak” the land and harvest its finite resources, it becomes apparent that you lack the dictatorial power the Captain once wielded. Somewhere in those 30 intervening years, the people of New London established a democracy for themselves — the scoundrels! Yes, in one Frostpunk 2’s biggest and most defining features, you’ll now have to work with the representatives of New London’s council before enacting any sweeping societal changes.

Yes, on top of the already dizzying amount of resource management, Frostpunk 2 also asks you to do the greasy work of a politician — whipping votes, wheeling and dealing, and making questionable promises. Despite how it may sound, it’s a fascinating idea, and one of the chief ways in which the game explores its ideas about the precarity of the social contract and the inherent contradictions within democratic societies containing irreconcilable worldviews. Whether you align with the extreme factions of your society — the Stalwarts and the Pilgrims — or you take a more moderate, majoritarian approach by siding with the New Londoners or the Frostlanders, each path is rife with friction, challenging your own worldview that you bring to the game.

Initiating a council session and immediately beginning the voting process is often not an option, as your proposal may only have marginal appeal among the disparate factions. To give your proposal a more surefire chance of passing, you must parlay with hesitant factions to gauge their demands. Sometimes, they’ll request a certain type of building constructed in exchange for their vote. Other times, they’ll simply ask you to propose their idea during the next council session, engaging in a tit-for-tat negotiation. In this way, Frostpunk 2 effectively gamifies the old-school transactional nature of pork barrel politics — with fascinating results. And if you’re already thinking, “Couldn’t I just promise a faction what they want to get their vote, and completely disregard them after I’ve gotten my way?” then I have to say, you’re way ahead of me, LBJ. Yes, that is absolutely one possibility — albeit one with some definite consequences.

You must be cognizant of how, and how often, you choose to manipulate the political landscape. Siding with one faction too frequently will cause the others to lose faith in your leadership. Routinely favoring a particular group can build “fervor” in both that faction and its opposition. If left unchecked, this heightened tension can lead to riots breaking out in your city’s districts. Failing to address these riots — either by placating the aggrieved group or by forcefully suppressing them with police — can deactivate the productive output of affected districts and eventually lead to their outright destruction.

A compelling aspect of this new democratic system for implementing the Idea Tree is this: laws passed by the Council are not set in stone. If a node of the Idea Tree no longer serves your needs, you can reintroduce the issue for another vote. For example, the game allows you to determine how alcohol is distributed in your society — either through city-run alcohol shops or privatized sales. The former increases Heatstamp (currency) revenue, while the latter boosts trust in your leadership. You might initially impose state-run alcohol sales when starved for tax revenue to expand the city. Later, if trust levels begin to fall, you can strategically repeal the old law, switching to the privatized model and bolstering the people’s trust in you — problem solved! If only someone had told Marie Antoinette about this one simple trick, perhaps she could have kept the French from exacting Liberté, Égalité, and Fraternité on her neck.

In all seriousness, this is unfortunately the area where Frostpunk 2 does feel the most underdeveloped. While it attempts to account for realistic political behavior — e.g. the right-wing Stalwarts will never negotiate on supporting labor unions, as it contradicts their worldview — the quid-pro-quo mechanics often feel overly simplistic. I lost count of how many Biowaste Hothouses I was asked to build in exchange for votes. Sure, support my proposal for food rationing, and I’ll build you a nifty little greenhouse in your district. It’s all a bit too contrived. If someone asked Frostpunk 2’s factions to jump off a bridge, they’d likely agree — as long as they got one more Biowaste Hothouse out of the deal.

Misgivings aside, Frostpunk 2 is a tense-as-hell expansion of the socio-political themes laid out in the original Frostpunk. It serves as the macro-level companion piece to the original game’s micro scale, effectively shifting its emphasis from man-vs-nature to man-vs-man. The game examines how ideological decisions made by those in power can create a very real thresher maw for the individuals subjected to them. There were times the game forced me to make decisions that I knew would result in a percentage of my population dying, and I made them anyway, rationalizing that the benefits to society would outweigh the near-term cost — a horrifying way to think, but such was the role the game had cast me in.

Frostpunk 2 later confronted me with the results of my dispassionate decision-making, presenting a monologue from a grieving child, orphaned as a direct result of my actions. It’s in these moments of humanity that the game strikes hardest. While you make these types of decisions all the time in strategy games, Frostpunk 2 remains in constant dialogue with you — reminding you of the cost of your choices and casting doubt on your ability to lead. That 11 Bit Studios has carved out such a unique angle for itself is a testament to their vision as a studio.

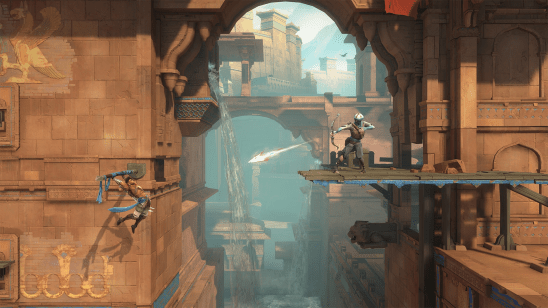

9. Prince of Persia: The Lost Crown – Ubisoft Montpellier

Don’t worry, this excellent game from Ubisoft was purely an aberration. The development team responsible has already been disbanded and the pitch for its sequel rejected. Keep calm and carry on.

The Old Citadel – Mentrix

It’s been a minute since Prince of Persia has had a day in the sun. Doubly so for publisher Ubisoft, who hasn’t put out a relevant or truly exciting release in quite a few years now. Fortunately for us, somewhere hidden deep within the corporate leviathan’s guts — gestating inside Michel Ancel’s Montpellier offices, no less — a stellar sidescroller was being assembled. Exceedingly fortunately for us, it seems this subsidiary branch of Ubisoft has managed to remain largely concealed from the Sauron-like gaze of CEO and NFT dipshit Yves Guillemot. Either he simply forgot to cancel this project or his attention was focused on tasks he would deem more important, like covering up the workplace misconduct of his executive team. Either way, it’s a win for everyone that a franchise lost to time has reemerged, miraculously unscathed by the rent-seeking tactics du jour of video game megacorps. We should all be so grateful.

Given that it’s been 14 years since the last major entry into this storied series, The Lost Crown takes the rather obvious role as a series reboot, both in terms of gameplay and plot. From the gameplay end, this is a 2.5D Metroidvania, full stop, and a damn good one at that. As for story, the game casts you in the role of Sargon, a member of the Avengers-like Persian warrior clan The Immortals. Right at the game’s outset, the titular Prince of Persia — Prince Ghassan — is captured and taken away to Mount Qaf, and you and the rest of The Immortals arrive, pursuing his kidnapper in tow. Only, once you arrive, you find that Mount Qaf has been cursed, freezing time itself within its Citadel.

So what sets this particular Metroidvania apart in an era where the subgenre is arguably more popular than it has ever been? For me it comes down to two broad areas of emphasis that are executed better than any other in recent memory. The first of those areas is combat — an element that many Metroidvanias, outside a few notable exceptions, leave quite a bit to be desired. Not so with The Lost Crown, which has a deceptively simple combat system that grows exponentially as each new element is layered into it. You’ve got your basic sword attacks, a slide maneuver that serves as both a quick dodge and a burst of speed that preempts a full sprint, as well as a parry system for defending yourself and capitalizing on enemy attacks for huge punishment. Nothing too crazy there, but it all works well together. As you dig deeper, you’ll find items like the bow, which enable you to keep combos going at range, or a grapple hook which doubles as a means to close the gap on pesky airborne enemies. Eventually, you’ll happen upon one of the game’s time powers — Shadow of the Simurgh — which allows you to save a copy of yourself in a specific position that you can then reset to later. For those out there that really want to unlock the true potential of this combat system, this ability is your secret sauce. Not only can you use these copies as cheeky defensive measures — zipping across the stage in a single frame to escape a dicey situation — you can leave a copy of yourself with a fully charged heavy attack, only to let loose a beam of energy from your swords, reset to your shadow copy, and fire off the same move again. The combat system rewards aggression, varied actions, and stylish execution in a way that has more in common with Devil May Cry than it does any other Metroidvania. Add in the game’s amulet system — which will be very familiar to Metroidvania aficionados — and you can setup builds centered entirely around a specific gameplay element. It’s extremely satisfying.

And yet, not to be outdone, it’s The Lost Crown’s platforming that truly sets it apart from its contemporaries. This is the Rayman team we’re talking about, after all. The act of controlling Sargon hits like no other recent Metroidvania has for my personal taste — there’s no floaty physics or momentum-based fuckery here, just direct and predictable movement dialed-in to a tee. In fact, I would go so far as to say these are my favorite controls for any game of the subgenre. It takes a lot for me to rave about a game’s platforming — a seminal video game mechanic that I have a true love-hate relationship with — so I was incredibly shocked to find I was welcoming the slow creep of challenge The Lost Crown sneakily builds to a devious degree by its endgame. The final challenges of this game are an unholy medley of spike walls, crushing blocks, and rotating saw blades that punish anything less than total precision with a swift reset. There are some especially sinister sections where you will need to remain off solid ground for upwards of an entire minute, all the while making use of the game’s toolkit of time powers to toggle between different dimensions, air dash across gaps, or even recall yourself to a previously saved location. I struggled with some of these individual sequences for upwards of 30 minutes, and yet the sense that victory was just within my grasp never gave way to sheer frustration — that’s how good these controls are.

And, as if to send a message that this is a capital-M Metroidvania, Ubisoft Montpellier went and recruited Gareth Coker for the game’s soundtrack — the absolute legend responsible for the brilliant orchestral stytlings of the Ori series. Perhaps not the most inspired choice for giving a new Metroidvania its own musical voice, except for the fact that they also brought onboard Samar Rad — better known as Mentrix. Born in Tehran and currently based out of Berlin, Mentrix adds a lot to the score’s sense of place, evoking the Middle East in ways that are both mysterious and beautiful — almost romantic at times. This is rarity in Western media — which typically falls into the trap of orientalism, getting the instrumentation somewhat correct but bastardizing most everything else. Instead, this is first Prince of Persia game that wears it’s Iranian setting on its sleeve, and is all the better for it. Just listen to the tracks “The Old Citadel” or “Sacred Archives” to hear some of what I’m talking about.

And I don’t want to gloss over the visuals here. The Lost Crown makes great use of its minimalist, cartoon-like art style to make its environments pop, and everything moves in such clean, crisp animations that reading enemy attack patterns is second-nature. Each region of the map is immediately visually distinct, with one area in particular — a series of ships, frozen in time amidst the apex of a turbulent storm — standing out as one of the most memorable.

So the bittersweet comparison to make from all of this is that The Lost Crown feels like the closest thing we’ve got to a Hollow Knight spiritual successor. While It deviates quite a bit when it comes to style and tone, the core gameplay loop is there. Of course that comparison stings a bit for fans of the 2017 cult classic, as we enter our 8th year with no real update on state of the long-awaited corporeal successor Silksong — a project that can perhaps best be analogized by Schrödinger’s cat, in that it is simultaneously a real video game and a piece of vaporware until it is observed.

Very much on-theme for the series, The Lost Crown feels like a Ubisoft game from a different time. It’s such an excellent game that it almost makes me sad. It’s easy to forget, Ubisoft being what they are today, that some of the best, most inventive, and immaculately designed games of the 2000s and 2010s came out of their network of studios — everything from Splinter Cell Chaos Theory and Rainbow Six Siege to Beyond Good and Evil and Far Cry 3. Worse still, in the months following The Lost Crown’s release, Ubisoft has disbanded the team that worked on the game, claiming that its 1 million+ in sales were a disappointment. How that constitutes a “disappointment” for a 2.5D game with a moderate production budget is beyond me. The act of disbanding the creative team feels like a tacit admission of the current state of Ubisoft — one where creating world-class video games that people really love is merely a happy accident in the pursuit of making profits. If you have dozens of team leads on a stalled production burning out and going on sick leave, if you have sexual misconduct at the highest echelons of your company, and if these problems are so bad that French authorities are getting involved, then maybe it’s long past time to re-evaluate the leadership of your company.

If you can put its publisher’s reputation out of your mind while playing it, Prince of Persia: The Lost Crown is the best game Ubisoft has put out in the current decade. It’s challenging in all the right ways, with plenty of secrets to uncover and excellent boss fights to overcome. It’s easily one of my favorite things I played all year.

8. Animal Well – Shared Memory

“This is the water, and this is the well. Drink full and descend. The horse is the white of the eyes, and dark within.” -The Woodsman, Twin Peaks, Season 3

Animal Well – Billy Basso

In a lot of ways, the experience of playing Animal Well defies description. At the game’s outset, you — a relatively featureless blob — are born out of a flower into an inky black subterranean world of some kind. The colors of the various cave features glow vibrantly, evoking something between the bioluminescence of deep sea lifeforms and the neon signage of 1990s Hong Kong. As the title implies, there are animals that inhabit this umbral environment, but their motivations are unclear. Some regard you with curiosity, others with hostility, while others still are completely indifferent to your existence. Whatever this place is, you don’t seem to belong here. Next to nothing about this world is communicated to you in text or dialog — you are left on your own to explore, to experiment, and to see how far the rabbit hole goes.

Animal Well is the brainchild and debut title from Billy Basso, who programmed the game and its engine entirely from scratch. Written in C++ and coming in at a meager 34 megabyte install size, the game features some mesmerizing pixel art, a hypnotic ambient soundtrack, and absolutely peak sound design — all created solely by Basso himself. Animal Well is a show-of-force for the interdisciplinary indie game auteur. Not since 2016’s Stardew Valley have I felt so stunned by what a single persona at a keyboard — given enough time — can create.

Technically speaking, Animal Well is a Metroidvania, but cavalierly assigning it to an established genre feels somehow wrong. Contrary to the typical conventions of the genre, your progress is only gated by the acquisition of new items very occasionally. In fact, most of the inventory can be filled out quite early on. More often than not, exploration is gated by your knowledge of certain mechanics — be that the behavior of an item you already have, the reactions that different animals have to those items, or sometimes the discovery of some multi-room spanning puzzle that you didn’t even register as a puzzle at first glance.

This dynamic is embodied in the sensation I got every time I found a new item. In a typical Metroidvania, the acquisition of a new item comes alongside a mental “Ah-hah” moment — you immediately realize that this new super missile is exactly what will open all those pesky green doors you’ve been seeing — whereas in Animal Well, the acquisition of a new item is typically accompanied by more questions. What can I even use this for? What are this thing’s limitations? What other items can I combine with this one? What if I jump onto it? Like a child with a new toy, you are left to experiment and find the bounds of what’s possible. Many of the game’s puzzles are designed around this type of discovery, oftentimes encouraging you to try things you just hadn’t considered before.

In this way, Animal Well is always attempting to communicate with its player, albeit non-verbally. The language it speaks is made up of subtle level design queues, emphasis conveyed by its lighting, and the various animal sounds echoing through its cacophonous soundscape. As a player, you need only pay close attention, and the game will slowly but surely reveal itself to you. If you can’t figure out a specific trick that you need to solve a puzzle, you can always venture down any other of its branching pathways until you stumble upon a more obvious hint that will reignite your motivation. Basso cleverly includes multiple, redundant hints for players, just in case the initial ones don’t jump out at you.

I want to be as vague about details of Animal Well as I can, because the more I say the more I risk spoiling the experience. So instead, I’ll just be blunt: Animal Well is one of the most innovative and unique Metroidvanias I’ve ever played. There is a level of hidden depth here that will keep you engaged long after the credits roll — a postgame that brought back old memories of playing through 2012’s Fez for the first time. There are secrets buried within Animal Well that are so deep and so cryptic that you are highly unlikely to discover them all on your own; these postgame secrets instead feel designed around crowdsourcing — of harnessing the collective brainpower of internet communities all contributing effort toward solving a singular problem. If you’re the type that appreciates games not holding your hand, giving you space to learn for yourself, while still respecting your time enough not to waste it on extraneous content, then Animal Well is a game you simply have to play for yourself.

7. Pacific Drive – Ironwood Studios

Few other games capture a love for the great outdoors or a love for cars in quite the same way as this game.

Instability – Wilbert Roget, II

Typically, there’s only so excited I can get about a survival game. At the risk of sounding dismissive of the entire genre, there are only so many ways you can handle a set of constantly decaying hunger and temperature meters, and not all of them make for compelling gameplay. It’s a testament then to the unique angle taken by Ironwood Studios’ Pacific Drive, that I found myself thoroughly hooked during my time with it. This is a first-person survival game, sans-combat, centered around the maintenance and upgrading of a car — a beat-up old station wagon — which is your only means of surviving the supernatural events and radioactive decay of the Olympic Exclusion Zone. Broadly, think the world of STALKER blended with the sensibilities and love for cars of Top Gear.

For Pacific Drive, inspiration struck Creative Director Cassandra Dracott during a lonely drive through Washington’s Olympic Peninsula. She’d been fascinated with the wilderness since childhood, spending the weekends camping out in the woods, driving to and from home in an old station wagon. There was something about the Pacific Northwest though, about driving through it with rain falling onto an isolated road, with music on the radio, that struck a chord. There’s this eerie yet beautiful, peaceful yet unnerving confluence of moods — one which this game, in all its Unreal Engine technical prowess, manages to capture brilliantly. While the writers at Ironwood Studios have penned a colorful cast of characters for Pacific Drive’s story, it’s the Washington Exclusion Zone, and all the strange anomalies therein, that steal the show as the de facto main character.

In Pacific Drive, your car is everything. It’s your transportation, your armor, your protection against the elements, your main source of light, the vast majority of your inventory, your scanner to find resources, and even your mobile crafting table to transform those resources into usable items. The condition of the car at any given time is significantly more important to a run than your own character’s health. You oftentimes don’t realize just how important it is until you become separated from it, but once you are for any significant period of time, the feeling of being naked and afraid is pretty keenly felt.

If you’ll spare me a moment, I’ll share an anecdote: I had a moment in my playthrough where I was driving through a toxic swampland in pitch black darkness when my car suddenly ran out of fuel – right in the middle of waist-high water. The scanner to search for fuel is built into the car, so I fired that off before getting out, snatching the jerry can off the side of the sedan, and hoofing it. Unfortunately for me, the scanner didn’t pick up any fuel close enough to the vehicle, which was now an immovable brick, so I just had to pick a direction, aim my flashlight, and start walking. The situation continued to deteriorate further as the batteries in my flashlight died and I was forced to make due with igniting the occasional road flare in order to — barely — see where I was going. Keep in mind, this entire endeavor is time-bound, because if you remain on any map for too long, a radiation storm eventually closes in around you. Without a drivable car to escape in, you’re cooked. So, I’m trying not to think about how much loot and progress I stand to lose if that happens, trying to watch where I step so a rogue anomaly doesn’t jump out of the darkness and pre-emptively snuff me out, and all the while hoping I mange to hit a road soon. Finally, yes! Sweet asphalt never looked so good. So, I begin trudging my way along the pavement in search of a fuel drum, igniting multiple flares in a breadcrumb trail fashion so that I can track where I’ve been. Imagine for a moment how good it felt when I finally discovered not just one, but three(!) fuel barrels next to the rusted out frame of a car. I was going to make it! Had this been real life, I would have happily dropped to my knees and siphoned the gas, mouth-first.

It was a euphoric moment — one of near disbelief — that I managed to pull a victory from the jaws of a seemingly guaranteed defeat. There is no way I should have survived given how badly I had screwed up, and yet I did. I don’t know if there’s any higher praise for a survival game than this — for it being able, with gameplay systems alone, to organically create this kind of survival story.

Something else that Pacific Drive does incredibly well is integrate its mechanics and its world building together such that they build off of one another. Perhaps my favorite example of this is the Quirks System. Essentially, as you spend time in the Zone, doing runs and collecting resources, your car will — unbeknownst to you — begin accruing random “quirks” to its behavior. These can range from the subtle — shifting to park might kick off your dome light — to the not so subtle — when the battery gets low, the car might start jolting forward on its own — to the flat-out dangerous — when your car starts hitting high speeds, all of the doors suddenly detach from it. These maladies can only be fixed back at the garage, where a DOS-like computer terminal will prompt you for the logical sequence that causes the quirk. You might select some sequence like Steering Wheel —> Turns to the Left —> Headlights —> Dim. A lot of times, the symptom will be immediately obvious, but what exactly is triggering the behavior will take a certain amount of troubleshooting.

This system helps sell the idea that Zone, and the LIM energy therein, can attach itself to inanimate objects and alter their intended behavior in ways that don’t obey the natural laws of physics. It also adds to the atmosphere of the Zone as a liminal space, where the world and the objects within are constantly in a state of flux. As these quirks begin to develop mid-run, it’s not always clear whether the strange behaviors your car is experiencing are mechanical failures, a map-specific Condition, or the effect of some not-yet-understood anomaly. In fact, until I had familiarized myself with the scope of the Quirk System, I had just assumed that the things I was experiencing where bugs in the game code. So powerful was this world building device, that it was as if the game world’s LIM energy was breaking apart the functionality of the game engine itself. Eat your heart out, Kojima.

This is also the area where I am the most torn with Pacific Drive — it simultaneously over-explains itself while under-tutorializing. As soon as you get access to the Route Planner, the game floods you with a veritable wall of information — from every Junction’s Conditions to its density of resources to the degree of kLIM points you can expect to extract. However, the game never formally guides you through how you should make sense of all this data, leading to me making a lot of early game assumptions that I only later discovered were actually incorrect. Technically, this is not an ideal game design, however, I do feel that it helped to sell the strange, unknowable world of Pacific Drive. While it made for a frustrating learning experience, it had the effect of immersing me deep into this strange new world and entrusting me to make my own sense of things.

In this way, Pacific Drive is one of the best games of the year at tying together a consistent tone and a distinct sense of place. I love the way it commits to the first-person perspective, including and especially while driving the car. When your windshield cracks, it’s not just cosmetic damage that appears on the 3D model you’re piloting around — it is directly obstructing your vision in a real sense. If a Broken Bunny anomaly attaches itself to the back half of your car, beginning to slowly damage your vehicle, you aren’t always going to see it right away — but check the side mirrors and rear view and you might spot it. I also just love the vibes of this game — its all very chill, very cozy right up until it isn’t anymore, at which point the game can become incredibly stressful. To me, this is the ideal pacing for a survival experience: one where you can breathe a deep breath and enjoy some virtual tourism, coffee on your desk, but before too long you could find yourself leaned into your monitor, one eye on the obstacles in the road, the other on the speedometer — as if staring at it will somehow cause it to shift gears sooner — as the soundtrack similarly goes into overdrive mode. If that sounds like the right dichotomy to you, Pacific Drive will be one of the most memorable games you play all year.

6. Silent Hill 2 – Bloober Team

“James, honey, do you remember that time when I understood the emotional intention behind this scene? You were always were so forgetful.”

True (2024) – Akira Yamaoka

Imagine, for a moment — in this era of copious remakes — that someone decided to remake your favorite game of all time. How would that make you feel? Would you feel excited? Nervous? Angry, perhaps? Would you worry that the task to remake of your favorite game would be given — seemingly callously — to a studio that had never proven itself capable of the artistic or narrative talents required to live up to such a job? What if I told you that the publisher of this remake hadn’t had a single shred of quality output in the last decade that wasn’t related to a mobile game or a pachinko machine? Would you feel skeptical? Scared? Would you look into a dirty bathroom mirror — eyes so sunken into shadow that you stop to question your own reflection — and think “It’s ridiculous. Couldn’t possibly be true.”?

This is where I was at prior to the release of Bloober Team’s remake of Silent Hill 2. The original game from Team Silent — the 2001 PS2 release — is one of the few video games that I have a deeply personal relationship with. In my adolescence, I spent untold hours theorizing about the game, studying it’s symbolism, and feverishly posting about it in the message boards of the day. I was obsessed. An honestly, on some level, I still am. I recently replayed the game a couple years ago — opting for SH2 Enhanced Edition, the wonderful community restoration of the original Windows XP PC release, borked rushjob that it originally was — and practically everything, from the story to the atmosphere to the music, holds up unbelievably well. It remains an incredibly important game for me.

Of course, many other people feel the same way about this source material. After all, Silent Hill 2 doesn’t belong to me. But, like all great art, it felt like every minuscule detail of that game was speaking directly to me. That feeling made this an extremely difficult remake for me to get on board with. That said, while I have my gripes about the specifics — specifics that are exceedingly important — I don’t think it’s my place to gatekeep Silent Hill 2. So, with that prevaricating aside, let me get into the thick of it.

To this day, the undisputed gold standard of survival horror remakes remains Capcom’s 2002 Resident Evil for the Gamecube. It’s still an extremely notable release, if for no other reason than that it managed to take a certified classic, and supplant it as the definitive version of the game. These days, very few people will recommend you play the PS1 version of RE1 — save for its value as a historical artefact, or for diehard fans of the god-tier voice acting. That remake is so good that if I tell someone how much I love RE1, the unspoken understanding between both parties is that I’m referring to the 2002 release. It’s a high water mark, to be sure, one that even Capcom has never quite been able to replicate — 2019’s Resident Evil 2 is the closest they’ve come, but there’s still some details here and there that I prefer about the 98 release. Bloober Team’s Silent Hill 2 is certainly not the definitive version of Silent Hill 2. There’s still a lot of reasons to revisit the original game, which I’ll touch on in a bit. However, having played it now, I’m happy to report — maybe relieved is a more apt word? — that this remake is infinitely better than I would have thought prior to its release. I’m glad it exists, and I think, for those who have never played Silent Hill 2, this is a fine great point to experience it. I may have my own, personal critiques of it, but I can recommend this remake to others without reservation. Let’s talk about why.

There’s a few areas that this remake absolutely nails, and one of the most critical is the atmosphere. This game feels like Silent Hill. The fog is thick and oppressive when it needs to be — it roils and undulates as if it is a living thing, shifting and intensifying as if expressing the unspoken will of the town itself. The otherworld, air raid siren heralding its unholy arrival, is made up of palpable decay — the plaster delaminating from the walls like the blistered flesh surrounding a chemical burn, exposing the stained tile and rusted iron grating beneath. The soundscape is oftentimes quiet but never really silent — there’s always the distant, guttural sound of rattling pipes echoing through the distance or the high-pitched buzzing of a dimly glowing fluorescent light tube — giving you the constant, agitated sensation of being alone yet unsafe.

The other aspect that Bloober completely knocked out of the park are the level and puzzle design — areas where the original game always felt a bit lacking compared to its Capcom counterpart series, Resident Evil. Well, no longer, as this remake adapts the same core levels — Wood Side Aparments, Brookhaven Hospital, Toluca Prison, and the Lakeview Hotel — into intricately designed spaces where navigation, exploration, the unlocking of shortcuts, and backtracking all feel carefully considered. Not only that, but many of these same spaces’ signature puzzles make their return in one form or another, and nearly all of them are better than how they were originally presented back in 2001 — the apartments’ coin puzzle being a particular highlight. I was actually shocked that some of the remake’s puzzles were allowed to remain as challenging as they are — especially given how much hand-wringing typically goes on when AAA studios over-playtest their puzzles…cough…Santa Monica Studio…cough. I also love that they kept in the original Team Silent method for handling the map. James will still mark inaccessible doors and puzzles of note on his map as you explore — but the remake takes that one step further. The map is now accessible in realtime, with James simply pulling it out of his jacket pocket, the camera zooming in to inspect it alongside him, and you will actually see him pull out a pen to annotate it after making a meaningful discovery — a simple yet effective reminder to keep checking the map for clues.

Silent Hill has never really been a series focused on combat, rather, its inclusion has always felt a bit obligatory in nature. Given that, I was very pleasantly surprised at how Bloober Team was able to reinvent the combat while changing remarkably few details on paper. You still tote around a single melee weapon and eventually three distinct firearms. Melee attacks are mapped to the right trigger, while pulling the left one first will pull out your equipped gun and aim it. Other than that, the only other real combat input — and the biggest change — is the inclusion of a new dodge button. Well, it’s less of a dodge, and more of a short juke; don’t expect James to be busting out Elden Ring fast-rolls or anything. The core loop basically comes down the fact that enemies have hyper-armor to some of their moves, and can attack at the same time as you. If you aren’t ready to dodge out of the way because you’ve already committed to an attack with your wooden plank or steel pipe, you’re going to take damage.

The end result is a combat system that’s elegantly simple yet hugely satisfying — with just enough built-in clumsiness to the stability of aiming, as well as unpredictability to the enemy behavior and damage model that you’re never quite fully confident you can take on an enemy without sustaining some damage in the process. Combine with those elements the greater emphasis on resource management — bullets and health items are now much more scarce than the original — and you have a satisfying, Resident Evil-esque meta-game operating over all of the combat encounters. Is it worth taking down this enemy with my gun and expending the bullets, or do I risk going in with melee to save the bullets and potentially risk losing health?

I was also particularly impressed with the amount of mileage Bloober was able to get out of the original roster of enemies. Spoilers, I suppose, but this remake doesn’t go adding new monsters to SH2’s South Vale — outside the occasional boss fight, you’re still primarily fighting Lying Figures, Mannequins, and Bubble Head Nurses. Each one of these has a single alternate variant that you will come across as you navigate deeper into James own personal hell, but that’s about it. I never found this to be a problem, even considering the remake’s roughly 2X greater length than the original game. It’s a testament to excellent AI programming that each enemy feels unique, exhibiting completely different behavior from one another. The biggest standout in the game are, hands down, the Mannequins, who have evolved from humble beginnings to become the single scariest enemy I’ve encountered in a game since Metro Last Light’s spiderbugs. The Mannequins, clever little bastards that they are, absolutely love hiding around corners, sitting impossibly still riiight up until the moment you wander too close, or center your view on them for too long, at which point they spring to life and rush you with attacks. Not only that, but if they sustain enough damage, they may chose to retreat instead of continuing the fight; if you don’t finish them off quick enough, they’ll flee the current room, only to post up behind the next door frame or ambush point they can find. Throughout my entire playthrough, I never got fully comfortable with these things — they easily made me jump out of my skin a dozen times over. Bloober really cooked with this one. Oh, and in case you’re wondering what their variant might be — don’t. Yeah, I won’t spoil that one for you, except to say that it must have been a good day at the Bloober offices when the developer responsible showed off the first prototype for that nightmare fuel.

In other welcome news about this remake, Akira Yamaoka — ever the rockstar video game composer — returns to his masterpiece score, expanding upon its themes as well as its scope, and the result is a sprawling collection of soundscapes that manages to completely submerge you into the fog-enveloped, pseudo-liminal space that is Silent Hill. I have so much personal respect and admiration for Akira Yamaoka, that to hear him revisit what I and many others consider to be his best work got me incredibly emotional over the course of the game. The moment about halfway through “True (2024)” where those 4 piano notes solemnly ring out, as if quietly emerging from a shroud of mist, still makes me emotional to this day. The moment when it plays in-game, as James sits down in front of a CRT TV to watch the VHS he made with Mary back when she was still alive, still gives me chills to this day. One of the greatest moments in gaming history, translated deftly to the modern era.

Given the dramatic weight and density of characterization present in scenes like this, the acting was a central component of Silent Hill 2. While not what everyone would immediately recognize as good acting, the original cast were unforgettable for the deep humanity and eccentric style they brought to their respective roles. Bloober Team’s remake, by and large, manages to recapture most of this — delivering by and large more consistent performances, but losing some of that secret sauce in translation. Those Lynchian, not-quite-lucid character interactions that were so strangely off-putting yet remarkably potent with meaning are all but gone here, traded in for a more traditional — technically more professional — acting style that will likely work better for a universal audience. Things are, in general, less weird in every interaction. Just compare the scene where James and Angela meet for the first time in the cemetery, and the way Angela responds to James saying he’s lost. “Lost???” There’s something about the original reading of that line — combined with the uncanny animation of that early PS2 era — that set the tone for the rest of the game to me — it seemed to suggest that this town is full of lost souls wandering through the fog without the understanding that they are, in fact, all lost, trapped in a purgatory of their own making. Angela’s reaction is one of perplexion on an almost spiritual level — she pauses for a beat, adjust her footing as if she isn’t seeing James properly, as if James had just confessed to something unconscionable. In the remake, that dream-logic type of interaction is gone from this encounter — with the remake leaning more on subtle facial animation to illustrate Angela and James’ states of mind. It’s not worse, per se, but it’s not to my personal taste.

A moment like that may be incredibly small, but I think it summarizes the dynamic at work in this remake fairly clearly. The new cast of actors actually do excellent jobs embodying their roles, although the creative decisions made by the writers and especially directors does impact which elements get emphasized and which are ignored. Luke Roberts’ performance as James Sunderland is much more humane, and due to that, I feel he’ll come across much more sympathetic to a new audience. He doesn’t exhibit as many or as severe of red flags in the remake, but the more naturalistic performance does mean that when he does have an angry outburst or a shitty comment, it sticks out for being that much more out of pocket. Scott Haining, who lends his voice to Eddie Dombrowski, absolutely crushed it — the new Eddie is fucking terrifying. Watching his new speech in Toluca Prison in remake gave me chills every time I saw it. Gianna Kiehl, who plays Angela, is perhaps the standout of the entire game — her performance is heartbreaking, the ways in which she shrinks into herself one moment, explosively reacting to a seemingly innocuous trigger word the next, felt painfully, honestly real. The penultimate encounter with her, in which you take on a boss battle related to her story, is haunting, and will sit with you long after you first experience it. In many ways, this remake leans into the idea that Angela is the heart and soul of SH2 — its most sympathetic character — and I do think that reading of the original work makes a lot of sense.

Unfortunately, there is one area where this remake really let me down, and that was in its portrayal of Maria and Mary — both portrayed by Salome Gunnarsdottir. While I do think her performance here was solid — at times, even incredibly memorable — the reality is that this story hinges, at multiple key points, on this pair of characters. It’s a tall order — Maria and Mary are the most demanding roles in the entire story, requiring the widest emotional range as well as the most raw, existential vulnerability. Not only that, but she needed to juggle two entirely separate roles, and be able to switch between them at will, sometimes within the same scene. It’s not all bad; there’s a new sequence added to Heaven’s Night for the remake where I think this new rendition of Maria really gets to come into her own. There’s even a lot of banter added between herself and James during their first hour together, as James bashes out car windows and just generally acts like a video game protogonist/lunatic that were very charming, and did a lot to help sell her character. All the new stuff, I really ilke.

Sadly, it’s the classic scenes — the most memorable in the entire game — that just wind up feeling hollow here. There’s the scene in the basement of the Brookhaven Hospital’s otherworld where Maria is meant to crash out when James accidentally mistakes her, once again, for Mary. Here, that scene feels shockingly phoned-in. Then there’s the moment that James and Maria have an unnerving, Lynchian conversation, each blocked from one another by prison bars. This is arguably the most infamous scene in original game, and yet, in the remake, the line readings are just completely monotonous — seemingly bored. There’s no venom in her voice when she says “I’m not your Mary,” there’s no real attempt to switch between the two characters voices. Maybe it was poor explanation of the scene by the directors, maybe it was her trying to be way too subtle in her performance, but whatever the reason, it did’t work. It’s incredibly disappointing, given how much the rest of the cast brought their absolute A-game. I won’t even get into how much of a letdown the final letter reading scene was — at that point I had already accepted the situation. It seems like Bloober tried to help out here, giving the speech some backing music as well as a montage to heighten the emotion — they even cut the letter down to be shorter — so hopefully the end result has the intended effect for new players. That said, it pales in comparison to Monica Horgan’s legendary performance, which still makes me emotional every time I’ve heard it.

Looking back, it feels great to say that I’m glad this remake exists. Bloober Team really managed to do the impossible and prove the haters wrong — myself included. That early marketing material for the game really was pretty rough looking, but in retrospect, this ended up being one of the brightest possible timelines. It’s easy to imagine a litany of ways in which this remake could have — should have — been a disaster. The fact that it didn’t, and the fact that it actually ended up being such a faithful passion project, truly feels like something to be grateful for. Now, my favorite game of all time can reach a new audience. Not only that, but the entire Silent Hill series has been resurrected with a new lease on life. It turns out, after all these years, that the series got the “Leave” ending it always deserved.

5. Balatro – LocalThunk

90,000 chips…Yeah, I think I got this one.

Main Theme – Louis.F

At the highest and most literal level, Balatro is roguelike deck-builder game where you attempt to beat an escalating ladder of static point thresholds — called blinds — within a limited number of poker hands. Upon closer inspection, however, the game reveals itself as something stranger: a deranged, long-lost ROM hack for a video poker machine, pulsating with occult energy. It remixes elements from divergent traditions — most notably integrating Tarot’s Major Arcana as consumables that alter your deck’s composition — while inventing its own arcane systems, like Planet Cards that permanently enhance the scoring potential of specific poker hands.

The true wellspring of its madness, as hinted by the title, lies in its roster of Joker cards. These function as persistent rule-breaking passive modifiers, warping the mathematics of victory in ways that range from subtly mischievous to gloriously game-destroying. Certain Jokers twist probability itself — creating snowballing payouts for common hands like Pairs with each successive play — while others corrupt Poker’s own axioms, redefining Flushes and Straights such that they require only four cards instead of the usual five. For all their chaotic potential, the Jokers’ individual effects are elegantly simple to understand. It’s through interlocking these modular building blocks across the course of a given run that they can give rise to entire playstyles — as specific as amplifying a single suit’s power or as broad as weaponizing unspent funds into compounding interest.

Structurally, Balatro is refreshingly straightforward, allowing all the game’s complexity to be centered around its deck building aspect. A run is divided into 8 antes — or levels — and each of these features 3 opponents: the small blind, big blind, and the boss blind. The small and big blinds are completely vanilla matchups — each simply requiring slightly more chips than the last to defeat. The boss blinds, on the other hand, are where things get tricky — these introduce unique debuffs that you have to attempt to play around. Some boss blinds will hard counter a specific suit — setting the chips and mult to zero when scoring them — while others are much scarier — one boss, “The Arm”, will permanently de-level each Poker hand you play against it. Coming up with creative ways in the moment to deal with the boss blinds, as well as keeping your deck flexible enough to avoid getting hard-countered by them, is central to the meta of Balatro.

A significant part of the thrill of playing Balatro comes down to what information the game chooses to disclose to the player and what information it chooses to play close to its chest. The game could, for example, offer a score preview before you commit to a given hand — transparently telling you exactly how many chips you are about to rack up — so you can compare a few different options and determine the optimal approach to beat the blind. However, to do so would have robbed the game of its quick pace and emphasis on player improvisation. Instead of experimenting to find what works and occasionally winging it — all the while trying to hold the synergistic effects of your 5 Jokers in your head — the game would instead devolve into an endeavor with all the vivacious energy of a TI-83. Rather than Balatro embodying the spirit of Poker — with its embrace of uncertainty and the occasional necessity for blind confidence — while breaking nearly all of its rules, you would instead have a game of decision paralysis, where for every moment of action is bogged down by double- and triple-checking every detail.

Of course, nothing is going to stop you if you’d rather play Balatro with an optimizer mindset. If what’s most enjoyable to you is to play with a pad of paper and a calculator in front of you, you absolutely can. There’s no turn timer that’s going to impede your idea of “fun” — perverted as it is — but I’d encourage you to try the Phil Hellmuth method instead. Yes, you’ll risk the same spectacular failures that might get you meme’d on, but when you succeed, the victory will be all the sweeter.

Live fast, die young. Do lots of experimenting and you’ll find so many unexpected ways that you can twist and break Balatro. Hell, play your cards right and you’ll find some setups that don’t even require Poker hands — you may just lay down a high card and let your Jokers do all the goofy chip math to make a single Jack worth more than a Royal Flush. Who needs card counting when you’ve got Joker Algebra?

Balatro shines brightest when a new Joker or card effect appears mid-run, inspiring you to completely reorient your entire deck around it. The moment your new strategy clicks and the cascade of point calculations spirals into absurdity — animations speeding up to keep pace with your band-busting play, point totals igniting NBA Jam-style — you’re hit with a rush like no other. For my money, no slot machine in existence can rival that level of pure dopamine release. It’s easily the most addicting game of 2024, so please just remember to play responsibly.

4. Lorelei and the Laser Eyes – Simogo

Excuse me, ma’am, do you happen to know anything about Strobogrammatic numbers? I’m really stuck on this one puzzle.

Misdirection Bossa Nova – Linnea Olsson, Jonathan Eng, Daniel Olsén

There’s a line several hours into Lorelei and the Laser Eyes, as the mysterious Owl Girl recounts a piece of folklore to you, that I think sums up the dynamic of the entire game very succinctly. “He found that art is only as good as its spectators.” Much the same then, Lorelei and the Laser Eyes will only be as evocative and transcendent a game as you allow it to be. If, like me, you solemnly swear an oath with yourself not to resort to a guide or take a curious glance at YouTube, then this game can be an enrapturing experience bordering on obsession. You too can pour over a sprawling list of keywords, roman numerals, and cryptographic mappings of shapes and numbers. You too can find yourself taking screenshots that you open in photo editing software just to solve a maze or flip the image perspective 90 degrees. You too can find yourself reaching for a sheet of graph paper to really nail down how to add the areas of three shapes together. You too can revisit each document you’ve collected in the game, hoping against hope that perhaps this could finally be the puzzle where you need the phases of the moon for a particular month in 1847, because dammit, if not now then when. This is the type of mind-bending experience that could await you on the one hand. Then there’s the other type of experience: you look up the answers in a guide, and you input those answers — game solved. Where’s the art in that?

This is game that challenges its players to make a pact with it: it will respect your intelligence as a participant in its great maze, but should you transgress, there will be no magic for you. Cheat the game, cheat yourself out of the experience you could have had.

In Lorelei and the Laser Eyes, you play as an unnamed woman who receives a mysterious invitation to an abandoned hotel in central Europe — possibly, maybe Italy, but that isn’t certain. The man’s motivations for inviting you, as well your own for agreeing to meet him, remain unclear. Upon your arrival at the Hotel Letzres Jahr, you are greeted — in very Resident Evil fashion — by a sprawling structure, its many rooms gated by innumerable locked doors, strange clock puzzles, and safes to crack. What seem to be bloody footprints line the hallways of the hotel, their red color the only visible hue on a canvas of black and white. Things feel decidedly off. Even the exact decade remains elusive. Your character’s style of dress as well as the architecture of the building suggest the 1960s, yet the presence of presence of 1970s-like tape-based computers and 1990s era video game consoles betray that notion. The only way to piece things together is by forging ahead, assembling information, and solving the dozens of puzzles laid before you.

Perhaps the greatest praise I can offer Lorelei and the Laser Eyes is that virtually every detail within it holds some degree of significance. Whether it’s to add another wrinkle to the mystery of the game’s story, or to give you a subtle hint towards solving an upcoming puzzle — oftentimes both simultaneously. This type of seamless integration of mystery and puzzle design is what had me fall in love with developer Simogo’s early work way back in 2013 when they released the phenomenally spooky, Swedish folklore-inspired Year Walk for iOS. It’s been exciting watching their trajectory in the decade since: their last game, a fairly significant departure into the realm of dreamy synth-pop rhythm game, Sayonara Wild Hearts, remains one of my favorite games in the Annapurna Interactive publisher catalog. Lorelei and Laser Eyes, by contrast, feels like a triumphant return to form for the small Swedish studio.

Style and atmosphere drips from practically every frame of this game. The strong, angular lines of low poly geometry are contrasted with high detail photography that is projected on top of it, evoking memories of blocky PS1-era graphics but with crisp details that create emphasis. The details are typically strongest in the center frame of each of the game’s static camera angles, before trailing off into abstraction around the edges and transition points — reminiscent of a concept artist’s sketchbook. The cutscenes evoke the silent film era, with dialogue overlayed atop key animations, framed such that the eyes of its subject remain unnervingly off-screen. Then there’s the music — composed by longtime Simogo collaborator Daniel Olsén — which assembles a sonic pastiche for the game that stitches together distinctly human warmth — jazzy Angelo Badalamenti-esque basslines, surf guitars, mysterious piano, the intimacy of vinyl record grit — with colder digital tones — spacy synthesizers, Akira Yamaoka-like atmospheric noise, chiptune arpeggios mixed with a low-pass filter — to gorgeous effect. This is one of the best game soundtracks of the year, hands down, adding a distinct layer of identity and mood atop the narrative concepts of the game’s experimental story.

In Lorelei and the Laser Eyes, you’ll feel a rush of dopamine you each time you manage to piece together a solution to one of its cryptic riddles. You’ll find yourself chasing that high — those “eureka” moments of elation are so frequent and paced out in the game that it will become a driving force that pulls you through it’s 20+ hour playtime. There’s always enough branching paths of puzzles at any given time that the moment that if you find yourself getting stuck in one area, you can allow yourself to mentally drift toward something else. The game will also, at times, necessarily grind your momentum to a screeching halt as you exhaust the last remaining avenues you had for exploration. In these moments, you’ll be forced to finally confront that one puzzle you’d had on the back burner for the last few hours. These peaks and valleys are the duality of any truly difficult puzzle game, and Lorelei exemplifies them better than any game I’ve played since 2016’s The Witness. You’ll feel the utter despair of feeling like you have zero clue how to progress, but through time and sheer force of mental will, the game will have you feeling like a damned genius all over again.

Given its rather high degree of difficulty, a really smart design choice the game makes is to minimize the friction between the player and the puzzles themselves. It keeps a dead-simple control scheme where the stick controls movement and selections, and every other button is interact. That’s it. If you press interact and there is nothing to interact with, the status screen will open, featuring your inventory as well as your character’s “Photographic Memory” (i.e. a saved version of every significant piece of evidence you’ve come across thus far). This minimalist control scheme, while a tad extreme, has the desired effect of removing the controls from your mind. There’s no puzzle you will encounter where you have to think, “Oh, I forgot to try that type of interaction with the weird door”. If something requires an item, the inventory will open to prompt you. If it doesn’t, it won’t. It’s a small thing that you likely won’t pay much mind to, but it frees up your mental bandwidth to focus on the information at hand.

While the game will give you all the tools and information you need to succeed — you’re not going to have to consult Google for something that you don’t have pre-existing knowledge of — it decidedly will not give you a means for note taking. There is no ability to place your own pins on a map, or annotate your Photographic Memories, likely because any tool that the developers could have provided you would have proven woefully insufficient. The game takes the stance that there is no substitute for pen and paper, and will even go so far as to explicitly recommend that you play this way. For some of you, that may sound like a chore — a relic of gaming past. If, on the other hand, that sounds as refreshingly radical to you as it did to me, then Lorelei and the Laser Eyes is going to feel like scratching an itch you forgot you had.

Lorelei and the Laser Eyes caught me totally off-guard. I went from barely being aware of its existence to completely head-over-heels in love with it over the course of its first few hours. This is a masterpiece puzzle game, easily the best game Simogo has ever developed. In a lot of ways, it’s a love letter to gaming past. I’ve already mentioned Resident Evil, but there’s some beautiful Silent Hill 1 easter eggs buried in here that had me positively gushing when I discovered them. And yet, the game feels entirely distinct in its identity — a patchwork collage of memories, characters, narrative and gameplay concepts, and wickedly confounding puzzles wrapped in a noir-sheen. If you’ll allow it to weave it’s spell on you, you’ll be in for an unforgettable sojourn to puzzle solving nirvana. I only hope I haven’t given too much away.

3. Persona 3 Reload – P-Studio

This is still the best Persona awakening scene in the series. Change my mind.

Color Your Night – Atlus Sound Team, Lotus Juice, Azumi Takahashi

I remember, in the spring of 2023, staring at a grainy, bootleg-ass video clip of Yukari — signature bow and arrow in hand — and thinking, “That’s a nice fan leak, but fat chance, Atlus doesn’t do remakes.” Sometimes, being dead-wrong can be an awesome experience. As if to drive home the surreal moment, confirmation of the long-awaited Persona 3 remake (now dubbed “Reload”) came out of an Xbox event of all things, and the announcement came paired with a trailer featuring Reload’s absolutely stunning, aquatic-themed art overhaul as well as a brief teaser of Lotus Juice’s triumphant return on the new track “The Meaning of Armbands”. “Atlus, you beautiful bastards, you really went and did it,” I thought. “We’re so back.”

Perhaps the greatest achievement of Reload is the way it manages to transform the exploration of its singular mammoth dungeon Tartarus — which, to be less than charitable, could have proved monotonous and laborious by modern standards — into an addictive gameplay loop that is the bona fide highlight of the game. It manages to do this in a few ways. Firstly, and perhaps most significantly, are the changes to Shuffle Time — the post-combat reward system of Personas 3 and 4. Reload most directly borrows from the Shuffle Time system first introduced in the immaculate Persona 4 Golden, wherein the cards are ironically not shuffled at all, but rather presented face up for the player to draw from a random hand. Most hands feature some assortment of the minor arcana — sword, cup, coin, and wand — each of which has an associated positive benefit, be it extra money, EXP, a random skill card, or a random buff to your party. And of course you will sometimes see Persona cards pop up, which allows you to expand your Persona roster outside of the normal Fusion system.

None of that should sound too different from what players of the original Persona 3 or FES will remember. However, where Reload makes a brilliant design choice is in the addition of rare major arcana cards whose benefits — contrary to how they were featured in P4G — persist until the end of the current Tartarus expedition. You unlock more major arcana for use in the deck as you progress through the story as well as after completing some optional areas. Their effects vary — everything from increased All Out Attack damage to additional card draws for all subsequent Shuffle Times to doubling all future item drops — and once you draw the limit for major arcana cards for a given night, you activate Arcana Burst, which increases the potency of all minor arcana cards for the remainder of your moonlit excursion. This simple change subtly encourages longer expeditions, incentivizing players to stretch the limits of their slowly dwindling SP gauges to reap even larger EXP and money drops as the night goes on. Further still, since you can never draw as many major arcana cards as you have unlocked, you have to weigh the tradeoffs associated with picking one over the other for the given night of battling. In this way, Tartarus can be as grueling as you want to make it — your runs of its labyrinthine floors as optimized as you feel like making them — but at the end of the day it’s up to you when you should throw in the towel.

Other small tweaks have been added as well — the addition of Twilight Fragments, a unique currency that can be used to unlock chests containing additional items or to recover your party’s SP adds an extra layer of decision making for players to consider as they ascend floor-by-floor. Petrified shadows (AKA breakable loot boxes) have been added to practically every floor, giving you some incentive to head down what would otherwise be dead-end pathways.

Enter then the revisions to the combat system, which do a better job of differentiating and balancing the strengths of each party member more so than any past Persona game. While Reload continues the series’ tradition of the protagonist being the strongest member of the team with a bullet, it carves out some satisfying niches for each of the other party members, giving them the ability to exceed the protagonist in key areas. For example, no matter how optimized your Persona stock, you’re unlikely to create a more efficient healer than Yukari or a more optimized crit build than your bat-wielding homie Junpei. This is thanks to the new Characteristic system, which unlock exclusive passive abilities for each character as you spend time hanging out with them during your Tartarus-free nights at Iwatodai Dorm. Take Yukari as an exmaple — with her characteristics maxed out, she has a ludicrous 75% reduction in the cost of all her healing abilities. That party-wide full heal that used to cost 40 SP? Yeah, for Yukari, she’s got the Costco Excecutive Membership of Personas, so she’s gonna be topping off your entire party for 10 SP. Meanwhile Junpei — the certified OG dumbass-with-a-heart-of-gold of the Persona series — gets an outlandish boost to his critical chances, allowing him to rack up 1 Mores like nobody’s business. I oftentimes found myself having more fun planning out my party members’ setups than the protagonist’s own Persona roster — something I can’t claim for any other Persona title.

And yet, as great as the new and improved combat is, the defining characteristic that sets P3 Reload apart from the other modern Persona titles, and what kept me so hopelessly hooked on it, is the intricate Gordian Knot that is the social sim half of the game. While other Persona titles present quite the challenge for obsessive completionists like myself — those looking to max out every Social Link, complete every side activity, and more or less complete a 100% playthrough — all of them pale in comparison to Persona 3 Reload. If you’re looking to achieve a “perfect” playthrough of P3R, be ready to break out all the stops. Timing is ludircrously tight here. Without exaggeration, you have 4 — maybe 5 — after school time blocks that you can burn over the course of the entire school calendar.

If you’re about this life, prepare to be juggling multiple spreadsheets, writing plenty of notes, cross-referencing and double-checking a plethora of details, saving early and often, and preparing for the game — in spite of your best-laid plans — to come out of nowhere just to kick over your sandcastle. Need more time to hang out with your school friends? Fuck you, bitch — you’re working at Wilduck Burger this week.