People like to talk about what the singular best years for video game releases were. Was is 1998? We got Ocarina of Time, Half-Life, Metal Gear Solid, and Resident Evil 2 all in that year. Was it 2004? That year had Halo 2, Half-Life 2, Metroid Prime 2, Metal Gear Solid 3, and GTA: San Andreas, all released within less than a month of one another – holy shit. Was it 2007? This is my pick – it had Portal, Call of Duty 4: Modern Warfare, Half-Life 2: Episode 2, Halo 3, Rock Band, Super Mario Galaxy, Mass Effect, Team Fortress 2, and Bioshock. Other heavyweights to me include 2013 and 2015 and 2017.

Enter 2023. In the aftermath of the pandemic and a slew of delays – including a sputtering start to the new generation of consoles – this is the year where it felt like things were finally clicking into place. The year got off to a bit of a slow start, but by summer it was just release after release until the very end. Naturally, I wasn’t able to get around to everything I wanted to get my hands on in such a crowded year, so I’ll have a few disclaimers here in a bit. But yeah, all in all, this was an incredible year for the release calendar filled with some massive hits and – sadly – some massive misses. The only downside for me is that, with so much having crowded the 2023 calendar, what’s left to still come out in 2024…? Whatever, that’s an issue for another time – we’re focused on the good stuff of 2023 today, so let’s get to it.

All that said, let’s get into my personal favorite games of the year.

Real quick, a couple disclaimers –

Quick obligatory notes:

- This is a ranked Top 10 list with 3 honorable mentions (unranked).

- Each game features a link to one of my favorite pieces of music from its soundtrack or to a clip of the game. Feel free to listen as you read.

- I consider the release timing of Early Access games based on when they exit Early Access, or enter V1.0.

- Remakes (which are becoming even more common these days) can be on my lists, but only if they are substantial enough in that the game is something fundamentally different. Examples of games I counted in 2019 were Pathologic 2 or Resident Evil 2. In 2020, I didn’t consider a game like Demon’s Souls (even though I loved it) because it is mostly a visual overhaul to the 2009 original game. Hopefully that distinction makes sense and isn’t just arbitrary to you.

Pile of Shame (games I didn’t have time to play):

- Star Wars Jedi: Survivor

- Darkest Dungeon II

- Armored Core 6

- Lords of the Fallen

- The Talos Principle 2

- Avatar: Frontiers of Pandora

Okay, with that out of the way, on to the list…

Honorable Mentions:

Final Fantasy XVI – Square Enix Creative Business Unit III

This is feeling like one of those cinematic clash things. Best mash square like always.

Full disclosure: I don’t play MMOs. So, while I can’t speak on it directly, I have heard lots of good things, from people whose opinions I trust, about Final Fantasy XIV. I’ve heard praise heaped upon it, lots of which centers around the world and storylines and characters crafted for it, with many claiming it to be some of the best in the long-running series. So, while I never deigned to play it for myself, you can imagine my excitement when I heard that Creative Business Unit III — Square Enix’s extremely punk-rock name for one of its many internal development teams — would be heading up the next mainline, single-player Final Fantasy game. Naoki Yoshida, credited with resurrecting the disastrous 1.0 launch version of FF14, would now be producing FF16 and bringing a lot of that same team along with him, with key artists reprising their role, the same lead writer handling the script, and Masayoshi Soken once again handling the music. I was primed to be excited.

Final Fantasy XVI kicks off with so much promise. Its introduction establishes the world of Valisthea, a dark fantasy realm in which entrenched ruling parties vie for control of its twin continents, Ash and Storm. In this world, the ability to harness magic is something you are either born with or you aren’t. Those that can wield it are dubbed “Bearers”, and their meager abilities to channel the elements are exploited for the benefit of the various political dynasties. Mothers of bearers give up their children at birth, condemning them to a life of servitude to their country. Set against this background are the Eikons, unbelievably powerful arbiters of the magical elements that each serve as their respective nation state’s superweapon. Eikons — which series veterans will recognize as summons from games past e.g. Shiva, Ramuh, Titan, etc. — are channeled through chosen individuals called Dominants. Their massive capacity for destruction — akin to that of a nuclear weapon — make them key to each nation state’s war machine, and no serious sovereign state can ensure its security without one.

You play as Clive Rosfield, eldest brother in the royal lineage of Rosaria, who is passed over for succeeding the throne when his younger brother Joshua is revealed to be the Dominant of Fire — conduit of the Eikon Phoenix. Rather than bemoan this situation as some insult to his honor, Clive instead takes up the role of Joshua’s Shield, swearing his life to protect him, and by extension, the Kingdom of Rosaria. The early hours of the game build up the relationship between Clive and Joshua — as well as their childhood friend Jill — just before, in a moment of shocking calamity, everything completely unravels around them. The intro of this game is a whirlwind of spectacle and violence and tragedy, setting the stage for the story proper in a way that had me on the edge of my seat. This is a Final Fantasy game that pulls exactly zero punches.

Given this dour world and darker tone, the writers of the game were smart to avoid the series staple moody-boy trope for their protagonist. Clive, brilliantly voiced by Ben Starr, is a much more honorable and sympathetic character, and dare I say one of my favorite leads in the entire history of the series. The thing is, he really needed to be. Clive isn’t just a “Bearer” in the magical sense, he’s also the load-bearing support for the entire game. See, in a series first, FFXVI makes the bold move to eliminate playable party members from the game, instead relegating all companions to the role of tagalong NPCs. They have no stats, no move list, no swappable equipment. It’s a real shame too, because some of the supporting cast are really memorable in their own right. Most specifically Cidolfus “Cid” Telamon, voiced by the incomparable Ralph Ineson, a man who I could happily listen to describe drywall for hours on end. But, at the end of the day, Clive has scant few friends along for his journey, and the total lack of playable party members is a series element that I sorely, sorely missed during my time with FFXVI.

I’m as shocked as anyone to be saying this, but it really is the lore of FFXVI that makes it stand out in the scope of other RPGs. There is tons of it, from the fleshed out histories and cultures of each of the game’s primary nations, to the way their brutal political actors seek to acquire and maintain power. There’s so much of it, in fact, that the game opted to include a system it calls “Active Time Lore” — a hilariously stupid name for something that I actually hugely appreciated. The system allows you to pause the game at any time, cutscene or not, and see a recap of the top 5 or so topics or characters that have been mentioned, giving you time to brush up on what they are or why someone was talking about it. Essentially, this system avoids the need to invent a “fish out of water” character to be constantly asking questions of everyone they meet, allowing the whole cast to feel grounded in the world and speak more naturally. You won’t find a lot of lazy exposition delivery. Instead, characters talk as though they’ve lived in this world long before you see them for the first time. There’s no “Joshua, you’ve been my brother for how many years now?” lines thrown in. It’s refreshing even as it was probably invented out of total necessity, given the sheer volume of terms and locations that get tossed around in the script.

To lead its more action-based gameplay, FFXVI put Ryota Suzuki in the role of lead combat director. His resume is a long list of heavy hitters from his time at Capcom, including Devil May Cry 4 and 5, Dragon’s Dogma, Ultimate Marvel vs. Capcom 3, and even Monster Hunter: World. Given that, it’s no surprise that Final Fantasy XVI is an absolute blast to play. The system is reminiscent of controlling Dante in Devil May Cry 4 and 5, revolving primarily on toggling between different “modes” that change up Clive’s fighting style and special attacks on the fly. Each mode has an associated element, imbuing his ranged casts with that element, but they also each have an innate power that can be used on demand with no limits. At first, that ability is Phoenix Shift, an extremely satisfying ability that warps you to the nearest enemy based on your directional input, whether that’s someone on the ground or in the air doesn’t matter. Later, you’ll unlock modes that change that innate ability to one specializing in aerials, a counter-focused shield guard, or even a special weapon with its own finisher gauge.

Most of the build variety in the game revolves around the limitation of only being able to equip 3 of these combat modes at a given time. Graciously, the game makes respec’ing your character a completely free process, incentivizing you to experiment, but this comes at the cost of cheapening the build-making process when everything can be undone and redone in seconds. And, while it is fun to align 3 different combat styles, creating a custom combat flow that makes sense to you and your playstyle, that is just about all the customization the game gives to you. While you can change Clive’s equipment, the options are just so minimalistic that nearly every decision boils down to “pick the sword with the biggest damage number”. There’s some equipment with special effects that you might consider using, but the limited options combined with the lack of other party members means that just about everyone is going to play this game with a very similar version of Clive. Sure, this entry is all about emphasizing the action gameplay, and this system is a lot of fun, but it can also feel hollow at times. In an era where so many action games blur the line between action and role-playing — with an abundance of skill trees, upgrade options, and weapon choices — it’s weird to play a Final Fantasy that seems to be running scared of such things. It’s not 2010 anymore.

And I think that’s the takeaway here with FFXVI. It’s heartbreaking, because the game does so much right. It has the skeleton of a great story in place, it has really great lore with lots of detail and dramatic weight to everything, it has a combat system that is immediately fun to engage with and has some decent depth to boot, it has Masayoshi Soken absolutely crushing it on the soundtrack (seriously, the way he weaves the Final Fantasy Prelude melody into the main theme “Land of Eikons” absolutely rocks), and it has some of the biggest and craziest spectacle I’ve seen in the entire series (let’s just say that the Eikons fights are when the game allows itself to go full anime mode). And yet, despite all of that, there’s another edge to the sword. There’s the absolutely mind-numbing, MMO-style sidequests (the game literally has you fetching dirt at one point), there’s the lack of deeper RPG mechanics, the lack of a party system of other characters for you to bond with, and a crazy inconsistency in quality between the main story and its optional content (for one, cutscene direction and character animation goes from exciting and fluid to stilted and rigid).

With FFXVI, Square Enix chose to min-max their whole game, prioritizing elements that I’ve found to be lacking in mainline Final Fantasy games for years, but at the expense of things that the series was already great at. The end result is a game of astronomically high highs and abysmally low lows. You get the stuff that everyone talked about loving about FFXIV, but apparently that comes with all the stereotypical MMO drudgery along with it. I do recommend playing FFXVI. I really liked it a lot; I even loved it at times. But if you decided to play it, do yourself a favor and skip all the sidequests. You can thank me later.

Lies of P – Neowiz Games

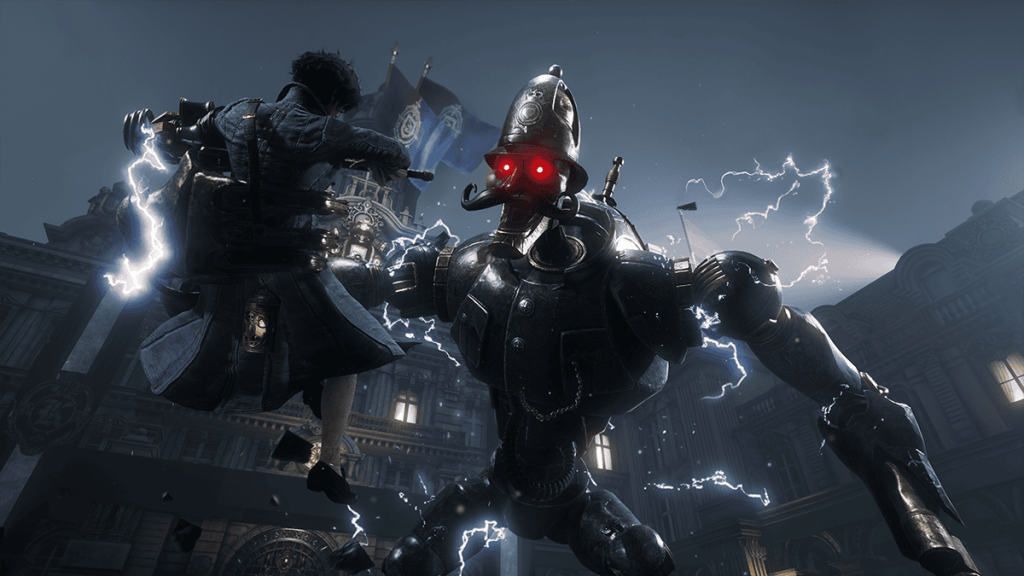

Imagine actually getting grabbed by that attack. Rofl git gud scrub. Try finger but hole.

There’s a few games on my list this year that I feel pretty torn on, but perhaps none of them more so than Lies of P. As a creative work, it is almost too derivative for me to recommend — and of a single, very specific developer no less. Sure, plenty of developers borrow elements from other games, and there is certainly no shortage of studios taking inspiration from Dark Souls, but this is a game that “borrows” all the way down to the UI, core systems, and entire movetsets of main weapons. It’s hard not to cringe at how hard it tries to evoke FromSoftware’s entire oeuvre, and I still feel a little uncomfortable about the plagiaristic vibes I get from it.

And yet, with all those caveats aside, this is perhaps the best Souls-like not made by FromSoftware, at least of the ones I’ve played. Like a great blended malt whisky, there is a distinct art to creating something new out of things you already have. Yes, you could go play Bloodborne and Sekiro again — and I wouldn’t discourage you from revisiting two of the best games of the 2010 decade by any means — but you could also reexperience many of the qualities that made them great, cherry-picked and reconstituted alongside some surprising expressions from elsewhere in the industry. Certain flavor notes are emphasized — ultra-fast enemy attack patterns or Bloodborne’s rally HP regen system, for example — while others are toned down — cryptic storytelling or convoluted gameplay systems, for instance — and the results may be more to your own personal tastes than you might expect.

Lies of P pitches itself as a retelling of Carlo Collodi’s Pinocchio, and in that regard I think it largely succeeds. Set in Krat, a city ravaged both by plague and an army of puppets that have been sent the Order 66 kill code, you play as the titular real boy Pinoccio, who is distinguished from the other puppets by his ability to tell lies and also sell Korean skincare products (just look at that face, goddamn). Seriously, since every combination of sliders in a FromSoft character creator seems to output one form or another of revolting hellspawn, it’s jarring to play one of these games as a traditionally attractive protagonist. The story itself is straightforward enough — remarkably so by FromSoft standards — and does its primary job of establishing a world filled with assholes for you rip and tear your way through. I don’t find it particularly compelling beyond that, and the lying “system” the game employs is little more than a series of binary choices that eventually result in a set of binary endings. Deep lore divers beware, Lies of P is not the game that’s going to inspire your next 3 hour video essay.

That said, I did want to touch on the atmosphere and music here a bit, because I do think the art style and in particular the enemy designs are particularly great, especially in motion. The steampunk-like puppet bosses are a real highlight, the staccato and unnatural way they look and move is really fun to look at…if, you know, you end up watching someone else play, and have time to appreciate that sort of thing. Some of the animation work in this game really is top-notch.

Contrasted against that quality are the environments, which have this odd, flat quality to them that never quite look like they have enough detail. There are moments where the atmosphere manages to overcome this however, and things become convincingly eerie, mysterious, and, at times, even serene. Adding to this is the excellent musical score, which is way better than it has any right to be. For some inexplicable reason, the game relegates a lot of the best music to collectible records that can only be listened to in Hotel Krat — the game’s hub world. A mystifying choice, given how evocative tracks like “Feel” or “Someday” are, but c’est la vie.

Lies of P gets a lot of comparisons drawn straight to Bloodborne, ostensibly because its Belle Époque-styled city of Krat gets mistaken for the more gothic flair of Bloodborne’s Yharnam, but when it comes to combat you actually feel the Sekiro influence more regularly. Much of the combat loop revolves around the timing of perfect parries in order to prevent damage while simultaneously building a hidden “stagger” gague on an enemy. Once active, indicated by a thick white outline around the enemy’s health bar, a fully charged R2 (heavy) attack will actually stun the enemy, queuing them up for a devastating visceral attack. Oops, those are actually called “X”, my bad. See, there’s some Bloodborne that slipped in there after all. Regardless, much of your time disassembling and hacking apart the puppet-denizens of Krat will be spent learning the flow of enemy attack patterns in order to keep yourself afloat. Dodging and blocking are also possible options, of various degrees of viability depending on the enemy. When holding block or simply mistiming your parry, you will take chip damage as punishment, but you will also have a fairly generous amount of time during which you can regain it by dealing damage. Because of this, you can design tankier builds based entirely around guarding like a brick wall and vampirically stealing your own HP back. Often these are your typical strength builds, where you haul around a comically oversized, Cloud Strife-esque weapon slung over your shoulder.

Where things get really interesting, and where Lies of P truly distinguishes itself, is in its weapon assembly system. Likely inspired by the modular nature of the puppets themselves, every weapon in Lies of P can be broken down into two distinct components — blade and handle — and then reattached to its opposite in any arrangement you can dream up. Blades influence a weapon’s raw damage and its effective range while handles influence its stat scaling and entire moveset. You can mix and match these to your heart’s content. Do you like the damage output and reach of the greatsword, but prefer a pokey-pokey moveset like the rapier? You can snap them together and suddenly you’re doing thrust attack combos with a blade the size of a tree trunk. Or combine a handle in something your character scales well with — motivity, for instance, this game’s name for strength — and a blade that has the certain kind of elemental damage you want. When you upgrade a weapon toward the +10 cap, this only upgrades the blade itself, so you’re free to move your blade around from handle to handle until you find a moveset that works for your playstyle. Each component of the weapon also harbors a particular fable art — the game’s name for special attacks that consume “charges”, which you build up by dealing damage — so you’ll have 2 at any given time. Finding synergistic weapon combinations can also be about finding the right special attacks that integrate with your build. It’s a genius system, and one that I feel I still only scratched the surface of by the game’s end. You can spend hours trying to dial-in just the right weapon, and it adds an entirely new layer to trying to hone a build beyond the traditional “strength/dex/quality” stat dynamic. Much as I love the “trick weapon” system from Bloodborne, I might actually prefer this approach, simply for the pure creativity it allows.

Further bolstering the amount of build-tweaking you can do, Lies of P adds a skill tree that it calls the P-Organ system. I’m still not sure if the name is supposed to be a joke or not, to be honest. Regardless, this system allows you to exchange a finite resource — quartz — for various benefits. Some parts of the tree will simply increase your Pulse Cells — healing flasks — while others will allow you more Amulet slots for your character. There’s plenty of niche options too, like increasing the window that an enemy will remain in staggerable status or upping the number of belt slots — quick item access — that the player has available. Within each of these “major” upgrades are smaller “minor” upgrades to things like charge attack damage or lowering the amount of damage you can receive when dodging. Point of all this being, when you combine the traditional Soulslike stats with the Weapon Assembly and P-Organ systems, you get a ridiculous degree of customization for your build. Souls-heads that go crazy for that sort of thing, this might just be your dream game.

It’s pretty clear to me that this is the side of FromSoftware’s games that Neowiz prioritized above all else. This is a game that is absolutely obsessed with build optimization and punishing difficulty of the ass-chapping variety. I’ve never been the best Souls player, but I’m a glutton for their particular brand of punishment nonetheless. However, Lies of P made clear to me what my limits were. I recoiled at how stupidly tough some of the boss fights in this game could be, and — unlike a game like Sekiro — I found I never actually overcame the difficulty curve, finding the right flow to begin mastering the combat. Instead, I flailed and struggled and cursed my way through just about each and every encounter. There are players for whom this will be exceptionally appealing, but for me it was a near-constant struggle.

I don’t want to go so far as to say the game is too hard. However, the way the difficulty was tuned here makes me question the motivations of the developer a bit. The point of the difficulty in the FromSoft games has always been to create a seemingly insurmountable challenge that players can eventually overcome through practice, wits, and sheer determination. It’s a loop that works because of the elation you get as you recognize your own improvement. Lies of P, by contrast, seems hell-bent on topping lists of “most difficult boss fights”. Beyond the first third of the game or so, nearly every boss becomes a 2 phase fight, with an entire healthbar gatekeeping the bad guy’s “true form”. Oftentimes, these 2nd phases behave wildly different than the first — rather than being evolutions of intensity — forcing you to become highly proficient at killing the first phase just to get an opportunity to begin learning the second. It straddles the line between “demanding” and “exhausting” a bit too much for my taste.

It’s a bit of shame the game feels so overtuned too, because many of its bosses are fantastic fights. Particular highlights to me are the King of Puppets, Laxasia, the Black Rabbit Brotherhood, and Champion Victor. If they had relaxed these fights just a bit, and relied less on the multi-phase design, I would have felt much more unreservedly positive about the game overall. Not everyone may be as bothered by this as I was, and for them Lies of P contains some of the best boss fights of the year. Just remember to pack your patience, as this is a game that will test its absolute limits.

Dredge – Black Salt Games

Honestly, I’d go mad too if I had to fish while sober.

The idea of “Cthulhu Fishing Game” might sound pretty strange at first brush, but Lovecraftian horror and the briny depths of the sea have always gone together like peanut butter and jelly. Look no further than the novella “The Shadow over Innsmouth” from the problematic man himself for the connective tissue. If game references are more your speed, that same novella was loosely adapted into Call of Cthulhu: Dark Corners of the Earth in 2005 and was also a partial inspiration for Bloodborne: The Old Hunter’s infamous Fishing Hamlet. Manga fans will recognize the connection from Junji Ito’s Gyo, with its nauseating depictions of human-fish body horror. Point of all this being, there’s something about the ocean that feels inextricably linked to madness.

Dredge then attempts to thread a needle through these thematic elements and the coziness of a fishing game. In Dredge, you take on the role of a lone fisherman in the early 20th century. After very little fanfare, you wind up shipwrecked in the small coastal town of Greater Marrow. The mayor lends you a new vessel and you begin using it to work your way back up — selling your daily catch to first pay back your debt and afterwards to begin upgrading your vessel. As things progress, however, you start hearing whispers from the locals about the dangers of venturing too far from port at night. At the same time, some of your catches start coming up to the surface…wrong. Some of the cod you haul aboard have a few too many heads and sometimes the crabs in your crab pots are wearing their brains on the outside. But hey, the fish monger pays you for them all the same — more money actually — so I guess everything is gucci?

The gameplay loop of Dredge is anchored to its accelerated day-night cycle. Fishing is generally fairly low stakes during the day — so long as you don’t allow your boat to careen into an outcrop of rocks. As the sun sets however, thick fog rolls in, reducing visibility down to just a few meters. Without powerful enough lights equipped to your boat, those rocky outcrops only render to the screen just moments before you are on top of them. Also working against you is the game’s Panic meter, represented by an eyeball at the top of the HUD that slowly opens before beginning to dart around frantically. The longer you spend out at night, the worse this effect gets, and the worse it gets, the more often you will experience Eternal Darkness-type sanity effects (think Amnesia: The Dark Descent for a more contemporary reference). Once in the Panicked state, the chromatic aberration gets cranked to 11, simulating the nauseating feeling of too little sleep on top of too much caffeine. Water spouts start forming freakishly close to you, seemingly magnetically attracted to your vessel. Swarms of crows hover overhead, excitedly cawing to one another at the prospect of stealing some of your hard-earned cargo. The only way to reduce this Panic effect is to wait things out until morning — at which point it will slowly dissipate — or to dock at one of the game’s various harbors and sleep it off.

The fishing itself is represented by a handful of straightforward timing minigames. The interesting part is how you stow your cargo. The inventory in Dredge uses the classic block-based matrix approach (think RE4, Apex Legends, or Escape From Tarkov), which is my personal favorite inventory system. The twist in Dredge is that your inventory matrix is the same shape as you vessel; you don’t have some nice 6×10 rectangle to work with. You also need to share certain tiles of your ship with your equipment — including rods, nets, lights, and engines. Want a faster ship? Well, that means less space for cargo. On top of the typical inventory Tetris, you also need to account for the fact that the game’s sea life aren’t all T and I blocks — rather, many of them are awkward shapes and sizes that can prove quite irksome to those of us on the OCD spectrum. It’s a really well thought out system that you figure out how best to optimize intuitively as you play. The game will subtly nudge you to the realization that many of the games weirdest fish shapes cleanly link up with other fish in the same biome, encouraging you to mix and match your haul instead of just spamming a single fish type. Oh yeah, and as your ship receives damage, certain boxes of the inventory matrix will become unusable, and any cargo that might have been already occupying that space will be lost overboard. So even you manage to pack your vessel perfectly with loot, you end up creating a situation where you’re gambling you aren’t going to hit anything on the way back to port. I love a game that has fun with its inventory, whatever that says about me, and Dredge has my favorite system of the entire year.

Perhaps the most refreshing element of Dredge however is that it resists letting each new mechanic become an albatross hung about the player’s neck. In your exploration, you may come across a piece of a treasure map, torn from a larger whole. If you’re so inclined, you can sniff around the surrounding area and discover the remaining pieces, aligning them to pinpoint the final resting place of a chest sunk beneath the waves. You might expect then, that in a game about exploring the high seas, for this mechanic to be repurposed numerous times over with a dozen or more map fragments scattered across the game world. You might expect that the treasure won’t spawn until you collect all the fragments, ensuring players follow the optimal sequence of events. You might even expect a tab in your quest journal, labeled “Sunken Treasures” or something like that, to track all the individual fragments you’ve come across during your adventure. And just like that, a moment meant to reward your curiosity and thorough exploration — a moment of intrigue and mystery — is reduced to a checklist.

Dredge resists this urge in commendable fashion. That treasure map, as fun as it is to seek out and solve, is the only one of its kind in the game. It isn’t tracked in any journal. And yes, you can find the treasure without ever locating even a single fragment of the map. There are plenty of other discoveries to be made as well, but I won’t delve too deeply into them all here — I don’t want to spoil everything. This is a game that invites its players to examine every inch of its map, trolling around the shoreline of every small landmass. It doesn’t give much in the way of map markers or waypoints either, instead allowing the player the ability to set pins on the map, Breath of the Wild style. Create your own system for what a fish pin or an anchor pin is meant to remind you of and mark up the map with them. Dredge is living proof that you don’t need dozens of collectibles or a map the size of a small country to make exploration feel meaningful.

By and large, Dredge achieves its twin goal of coziness and horror. It’s a game that I spent most of my time just vibing with, satisfied with its pleasant loop of seafaring, upgrading, and filling out a Pokédex of cosmic horrors. That said, there were certainly moments where I went a bit too far off-course and wound up clenching with my whole ass as I ran from some new, twisted nightmare. It’s these small bursts of fear in what is otherwise a fairly laid back experience that make Dredge such a unique blend, and it’s one I couldn’t put down until I had wrung it completely dry.

Top 10:

10. Homebody – Game Grumps

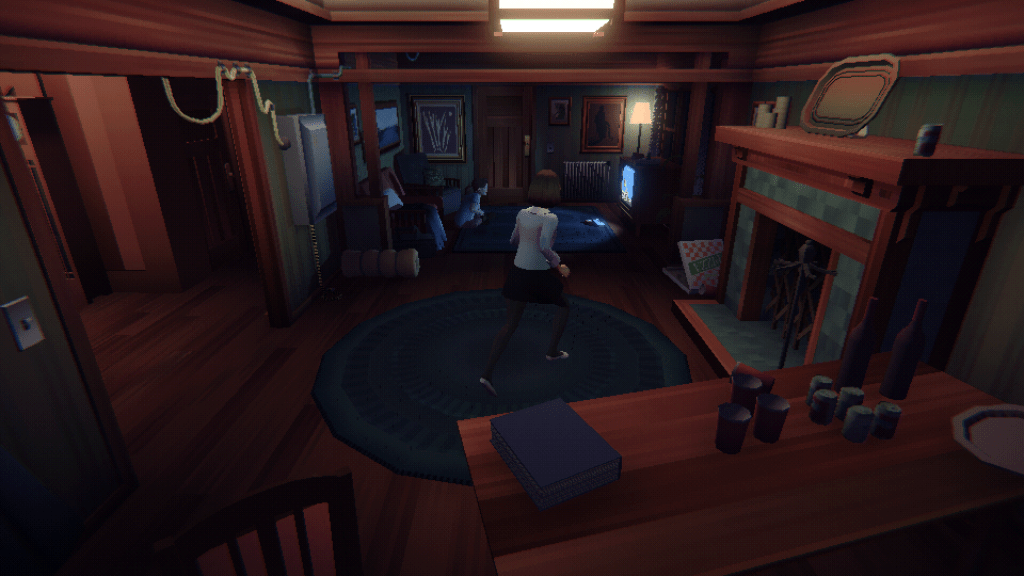

This house is full of monsters! How can you just sit there and eat pizza!?

Homebody has a classic horror setup: you are Emily, a woman in her early 20s who is running late to meet up with her hometown friends for a weekend of catching up. The Perseids meteor shower is about to happen, and Emily’s friends have rented a house out in the country to get a good view of things. The first night doesn’t go well. The house is strange — its rooms are stuffed with peculiar renovations, raw Romex wiring runs spaghetti-like from the fuse box to arbitrary holes in the floor, and many of the rooms remain suspiciously locked. In the kitchen is a thick binder that the owner left, outlining a long list of rules, including that the attic and basement are strictly off-limits for privacy reasons.

Halfway through the night the storm outside ends up knocking out the power, and things just get worse from there. As you fumble around, looking for a way to get the lights back on, you realize that the five of you aren’t the only ones in the house. A man in a mask appears — or maybe it’s actually a creature? — attacking you and your friends indiscriminately with a knife. With no way to fight back, you and your friends are all gored and left to bleed out, one by one. And then, just as quickly as the game drops its late title card, you find yourself back in the house’s foyer. Everyone is alive again, with seemingly no knowledge of what had happened — save for Emily, who is more than a little freaked out. In a now-classic video game twist, you find that you’re caught in the middle of a time-loop, unable to leave the house or work together with your friends. It’s only by investigating the house further — and solving its litany of Riddler-ass puzzles — that you have a hope of getting out alive.

In most survival horror games of this ilk, the documents and diaries you find scattered throughout the game world are usually some variation of “how things went bad” — page 1 will set up some ominous thing or another, and by the final page you will end up learning how the writer met their bitter end. The various reading material sprinkled throughout Homebody more often than not consist of safety pamphlets outlining all the ways you could inadvertently start a grease fire or get lung cancer from invisible radon exposure. Others offer mad ravings, drawing graphic comparisons between a house and the human body. These are a part of the world and their locations in that world make sense, sure, but their inclusion in a psychological horror game paints a grim picture of Emily’s state of mind.

See, as the game goes on and Emily’s psyche enters the foreground more and more, it also becomes clear that Emily has been suffering long before the events of the game. Her greatest fears have a lot less to do with scary houses and creatures brandishing knives, and more to do with whether her friends are pissed at her. In between your deaths and starting the night over you get little vignettes of story — sometimes brief memories and sometimes paranoiac premonitions of the future — and during these you’ll see Emily catastrophize over things which should be, at most, mildly stressful. She doesn’t really have specific fears you can point to, rather she tends to chase after bad thought spirals, losing herself to momentary obsessions with unknowable questions.

As Emily says at one point, in a moment of intense self-awareness, “Always nice to have fewer variables, you know? Being able to focus on one big, scary unknown kinda distracts from all the other little unknowns.” The big scary killer in the house is like this. He’s predictable — you can set a watch to his presence — and yeah, he’s gonna kill you, same as every time. He is a clear threat, and the rules with him are very clear as well: if he touches you, he kills you, and the loop starts over at 7:00PM. The same can’t be said about why Clive is no longer on speaking terms with you. Or whether your friendship with Francine is slowly deteriorating. Or whether you’re ever going to be able to solve this fucking fuse box puzzle. Or whether you’re failing your friends more and more every day and eventually they’re going to wind up dead and it will all be your fault.

If it’s not clear already, Homebody operates on a lot of the right frequencies for me. As a certifiable old-school survival horror sicko, the fact that this game takes clear inspiration from Clock Tower as well as oft-forgotten classics like The 7th Guest and D — melding time limited gameplay, a stalker enemy that you can’t fight back against, and just the right level of convoluted, unapologetically difficult puzzles — had already won me over in the game’s early hours. Then add in the way it seamlessly overlays a relatable, intensely personal story about a character struggling with various anxieties and OCD checking behaviors — placing you as the player into a position where your actions closely mirror the internal conflict that Emily is going through — and the end result is something I felt was really special. It’s a rare thing for me to play a game that puts me inside of a character’s headspace while simultaneously not short-selling the gameplay end of things. Homebody is one such game, alongside some personal favorites of mine like Papers Please, This War of Mine, and Her Story. I think this is a game that will fly under most, if not everyone’s radar, but you shouldn’t allow it to. To my great shame, it is one of the few truly indie projects on this list, but it should say a lot that I still think it belongs here in spite of what a huge year for game releases 2023 ended up being.

9. Super Mario Bros. Wonder – Nintendo EPD

This is karma, Mario. For all the Goomba lives you’ve so callously snuffed out in your long career as a plumber. Suffer, you sick bastard.

You have to imagine that Super Mario Maker was just as much of a curse for Nintendo as it was a blessing. While it wasn’t as much of a sales giant as other entries in the series, it did a lot for revitalizing the creative spirit of the classic games. Perhaps too good, as the game supplied the hardcore fanbase with the tools to create just about anything they could dream up. What came out the other side were some of the best Mario levels in many years. Player-made levels, untethered by the constraints that Nintendo had to make things accessible to a more casual audience, could zero in on some tiny element of Mario knowledge — say, that donut platforms pass through all other objects when falling but still allow Mario to stand on them — and craft entire levels around exploiting that. For a less hardcore Mario player like me, it was amazing because it felt like every highly rated community level had something new to teach me about a series of games I only thought I understood.

So then, if you’re Nintendo, where do you go from here? Now that you’ve effectively crowd-sourced your level design, do you just go back to Goomba-stomping and pipe-warping World 1-1 stuff for the masses? Pump out a desert level and a lava level or two and call it a day? Well, I’m sure they could have. Mario and financial success seem more or less inevitable. But as cynical as Nintendo can seem at times, it’s clear to me that there are internal ambitions within the organization to do great, creatively-fulfilling work…at least once every couple years. Super Mario Bros. Wonder is one such attempt, and the results pretty much speak for themselves. This is the most inspired Mario release for years, striking a balance between bite-sized levels built around unique gimmicks and hand-crampingly savage challenges for the truly Mario Maker-pilled among you.

Nintendo will never acknowledge it, but Mario has long been associated with recreational drug use. He’s a guy from the “Mushroom Kingdom” and eating said mushrooms makes him larger and more powerful…every conceivable joke about this has already been told five times over. Wonder finds Nintendo leaning into that joke to the nth degree, adding the new Wonder Flower mechanic — a powerup which, when obtained, doesn’t transform Mario so much as it does the entire level, resulting in outrageously trippy snippets of experimental game design that can only loosely be described as head trips. In some instances, levels will tear down the flagpole, pushing the entire stage beyond it as shrugs off the laughable notion of “rules”. Other Wonder Flowers will turn the level on its axis, trading side-scrolling for top-down movement and no jumping. Other times these sections turn into highly choreographed musical numbers, with Piranha Plants getting up out of their pipes and on their feet. These Wonder Flower sections, which are sometimes out in the open and sometimes deviously hidden, are where Nintendo pushes the boundaries beyond what was possible in any Mario Maker level. They are incredibly varied, and they go a long way toward giving every level a distinct identity.

And while the Wonder Flower is the most obvious distinguishing element of this game, it far from the only thing setting this game apart from recent entries. Another hugely welcome element is the addition of lots of new enemy designs — at least two dozen of them, in fact. Nintendo is just as adventurous with these concepts as it is with those eye-catching, trip-inducing flowers. The Skedaddlers are gopher-like enemies that run away from Mario as he approaches, all the while shooting seed projectiles at you. Hoppos meanwhile are sphere-shaped hippos whose bodies have a bouncy effect, allowing Mario to use them like a trampoline, even after rolling them into other enemies or wedging them into a nicely-positioned gap. A personal favorite of mine are the Hopycats, a spikey-headed enemy that mimics Mario’s jumps, threatening to poke you when you leap over them, but oftentimes manipulatable to reach hard-to-get item blocks. A lot of the stages in the game are based around the presence and utility of these new enemies, and while there’s still plenty of the requisite Koopas and Goombas populating the game’s levels, they really weren’t necessary here, given the sheer number of new additions.

Another great element is the difficulty rating for each of the game’s levels. Every level is marked with a difficulty between 1 and 5 stars. While this feature is in and of itself fairly mundane, including it was a means for Nintendo to spread around the game’s difficulty spikes rather than simply pack them all into the endgame. You’ll find some shockingly demanding levels pretty early on, but those 5 star difficulty ratings will prompt you when it’s time to break out the sweatbands and go full Kaizo mode. And, on the entire other end of the spectrum, every world is filled with little level snippets designated as “Break Time” — stages which have no difficulty rating and are oftentimes un-failable, intended to be short and sweet refreshers between the larger main courses.

Wonder also introduces a badge system, allowing you to unlock and equip any 1 at a time. Badges add a further level of optional spice to the levels. Some offer hand-holdy things for beginners, like giving you a mulligan the first time you make contact with a pit or lava. Others add unique movement abilities, like a same-wall wall kick or a hover ability. The final category of badges function more like the skulls from Halo — insidious exercises in masochism that increase the difficulty of the game by doing things like making Mario never stop dashing, or just outright making him invisible. They aren’t for me, but it’s a nice nod from Nintendo towards its most challenge-run obsessed fans.

The levels aren’t the only things with new transformations. Nintendo also added some new transformations for Mario himself, including the new elephant form, which I didn’t expect to like nearly as much as I did. Pressing the action button swings the elephant form’s trunk, making for a pretty useful side attack. If you find a body of water, Mario will fill his trunk with it, and then that same attack doubles as a way to hydrate different parts of the level to solve puzzles. There’s also a drill form that allows you to attack enemies by jumping at them from below, and you can get all topsy-turvy and navigate on the ceiling with it.

With all these new ideas surging through this game, it’s a shame that the boss fights are very copy-pasted, hop-on-his-head-three-times fights with Bowser Jr. They aren’t bad, but in a game with this many new ideas, they stick out as uninspired. That said, I do appreciate the variety of castles leading up to those bosses. The few times they go back to the old castle tropes, it’s as a cheeky reference filtered through this game’s specific brand of weird.

Super Mario Bros Wonder is just about everything you could want from a Mario game. It’s game design excellence packed into an extreme density — a 7-10 hour experience that never lets a concept overstay its welcome. It’s good to be reminded that Nintendo still has games like this in them. Now if only we could somehow get a Mario Maker 3 with Wonder’s mechanics built in…

8. Spider-Man 2 – Insomniac Games

There can’t be 2 Spider-Men. One of them must be an imposter.

There aren’t too many modern studios as dependable as Insomniac. At least since the start of the PS4 era, their output has been consistently high-quality — both when it comes to technical sophistication as well as when it comes to putting out a polished final build — and fairly frequent to boot. Sure, their games don’t ever really reinvent the wheel. They opt instead for tried and true gameplay systems that are certifiably fun, and stitch those together in ways that should seem obvious in retrospect. But sometimes games are just a good time, and that’s okay. Not every game needs to have ambitions to change the industry. In that sense, Spider-Man 2 is probably the most straightforward game on this list, but it’s also one of the most satisfying.

While the prior two entries have had PS5 versions with fancy features like ray-tracing and near-instant load times, Spider-Man 2 is the first one of these games designed around the PS5 hardware as a baseline. This is the first truly “next-gen” one of these games, and that fact is apparent almost constantly as you play — not because the draw distance is so huge or the game’s lighting is so great that you can’t stop gawking at it, but because it directly influences the gameplay. Web swinging in Spider-Man 2 is fast — very fast. The web swinging before upgrades in this game is still significantly faster than the web swinging maxed out in the original game. This is all due to PS5’s enforcement of a PCIe 4.0 SSD as minimum spec – allowing developers to design their data streaming systems around these drives’ astronomical read speeds.

Insomniac wasted no time in running with this state-of-the-art power — 2021’s Ratchet & Clank: Rift Apart leaned heavily on portal-based gameplay that showed off the ability to load in new assets at warp speed — but it pales in comparison to what it’s allowed them to do in Spider-Man 2. An example: during the colossal fight with Sandman that opens the game, Miles gets thrown — in a pure technological flex — from Manhattan’s Financial District through the interior of a skyscraper and back out the other side, all the way up the borough to Washington Square Park, all in about 3 seconds, all before showcasing the new slingshot maneuver to fling himself right back into the fight in just as little time. It’s a flashy bit of spectacle in an opening fight already brimming with spectacle, but it’s legitimately something that you’ve never seen another game do before.

With all that newfound speed, players will need an even larger playground to properly make use of it. Thankfully, Spider-Man 2 adds in some rather notable absences from the first game: Brooklyn and Peter’s home borough of Queens. The inclusion of these 2 new areas is very welcome, but they come with a rather clear design challenge: The East River. Problem is, in a game where the traversal system requires tall things to attach webs to, how do you make navigating a river fun? You could force the player to use the support pillars of the Brooklyn or Manhattan Bridges, and thus make swinging between the old map and the new one a bit of a chore. Spider-Man 2 has a fairly elegant solution for this dilemma. Pete and Miles now come equipped with “web wings”, a gliding apparatus that they can toggle on or off at will, getting a sudden burst of horizontal distance when deployed at the correct times. The flight controls take some getting used to, but once mastered, they allow for even faster movement than traditional web swinging alone. These now become your all expenses paid ticket to convenient borough-hopping. Plus, the East River is sprinkled with enough passing sailboats and barges that you can point launch off of if you need to regain altitude or speed, and both Pete and Miles will do a short “skate” animation across the water’s surface before fully plunging in for a swim — an additional safety net to keep player traversal zippy and forgiving. It’s very clever stuff.

That said, I don’t want to imply that the movement is without depth. Quite the opposite. Insomniac clearly wants people to have fun first and foremost, but players seeking to exploit the system to the fullest will find they have a plethora of options for building and maintaining momentum. And those that truly want to challenge themselves can head into the Options menu and disable Web Swing Assist, for an ultra-realistic experience. It’s not my personal cup of tea, but the fact that Insomniac allowed this to be a player adjustable parameter speaks to the level of confidence they have in their system. And they should. There’s no other open world movement system out there as fun as this one.

Combat is largely how you remember it, i.e. really fun, but with a few new twists thrown in. The most obvious change is the inclusion of a new parry option, which all video games are now contractually obligated to include, lest Hidetaka Miyazaki personally have the devs thrown in game design prison. The parry offers a nice risk/reward option that supplements the existing dodge without outright replacing it. The gadget wheel has now been removed in favor of a real-time control method using R1 + face buttons. It makes the learning curve a bit steeper to memorize the control scheme, but it keeps the flow of combat from being constantly interrupted — something extremely important for an action game as fast-paced as this.

But the key differentiator that sets this game apart as a truly great sequel isn’t just the refined combat or the reengineered web swinging. No, these sorts of mechanical upgrades are commonplace in big AAA sequels. Instead, it really is the story. Contrary to lot of big, financial cash cow games, this game leads with its characters. And these aren’t characters who are stuck in stasis, their motivations and arcs glacially creeping along on the off-chance their presence is required for the next sequel. Instead, what makes this series of Spider-Man games so enjoyable is in large part due to how much the characters evolve over time, how past events continue to matter and influence future events, and how the game isn’t afraid to have key characters die if it makes sense for the story.

At the start of Spider-Man 2, we have a Peter Parker dealing with adulthood absent the support system that Aunt May provided, whose dual-responsibility as Spider-Man makes it difficult to hold down a job. Mary Jane, now living with Peter, is struggling with her career at the Daily Bugle, weighing the cost of selling her integrity to appease the more sensationalistic tastes of her boss. Miles, having adjusted to the day-to-day of crime fighting of a full-fledged Spider-Man, is still haunted by memories of his father’s killer, Martin Li, as well as a pretty serious case of writer’s block for his college essay — the classic big-little stakes of being Spider-Man. Harry Osborn returns in good health — surprising everyone at his sudden and miraculous recovery — trying to rekindle his friendship with Peter even as he recruits him for his new environmental startup, his near brushes with death clearly driving him to change the world for the better. I could go on, but you get the idea. Outside of the intervention of a certain hunter (Kraven), almost the entirety of the plot is set in motion by these 4 characters and their interactions with one another.

Oftentimes, most of these character arcs reach their apex during gameplay, with the drama playing out over the course of a big brawl or some multi-phase boss fight. A particular highlight involves a bit of radical couples therapy that plays out alongside a boss encounter. It’s relatable stuff for anyone who’s been in a committed relationship, with all the sacrifices and frustrations that those can entail, and it manages to do this while riffing on an obscure bit of Marvel villain lore.

On the one hand, having the gameplay and story synced up like this should be a no-brainer. On the other, it’s easier said than done. Even a lot of films struggle with this — the action should help actively tell the story, not just be a distraction to keep things from becoming boring. In a game as big as this, it takes some really close collaboration between the scenario designers and story team to pull off these kinds of moments, and Spider-Man 2 is positively brimming with them. All of this, combined with the fact that Insomniac continues to find new ways to incorporate key members of the cast from prior games, allowing them to have arcs that span multiple games before fully paying off, is remarkable, even if they are very good at making it look easy.

Given the legacy of the much-lauded Sam Raimi film, it’s a pretty bold move to simply name your hotly anticipated superhero sequel “Spider-Man 2”. Insomniac, however, is nothing if not bold. This is an extremely confident sequel that elevates what worked in the first game, trims back what didn’t, and creates a compelling new story that kept web-yanking me back any time I tried to put it down. I’m actually excited to see where they go with Spider-Man 3, and I almost never say that about sequels. They’ve won me over, what can I say?

7. Dave the Diver – Mintrocket

Alright, which one of you jokers ordered the Hot Pepper Tuna?

Dave the Diver is a very eclectic cocktail of a game. There’s little splashes of just about everything. Sure, as the name implies, there’s diving. You’ll spend your days doing lots of that — equipped with a harpoon and a diving knife, you’ll make dives and collect as many fish and resources as you can manage to haul back to the surface. At night you’ll engage in the operation of a fast-paced sushi restaurant, à la Diner Dash. These are the two core halves of the Dave the Diver gameplay loop, but there’s so much more beyond that. For one, there’s farming — of both the flora and the fauna variety. There’s restaurant management — complete with hiring, staffing, and training. There’s a Pokedex-like catalog of fish to collect and fill out. There’s seahorse racing for you to gamble a secondary currency on. There’s even a visual novel sequence and a Metal Gear-esque stealth level thrown in there in case you ever get the feeling you’ve got this game figured out.

Playing Dave the Diver, it’s hard not to make comparisons to other indie slice-of-life games like Stardew Valley, but the longer I played the more I found myself drawing comparisons to Atlus’ Persona series. For starters, neither game uses a clock to reflect the progression of the in-game day, but rather the completion of individual gameplay segments. Time passes and day becomes night, but there’s no real urgency to it — a far cry from Stardew’s frantic rush to sow and harvest and profit all in time to hand out the all-important birthday gift. Instead, the passage of “time” serves to break up the gameplay into digestible chunks that feed into the larger loop. Look at any singular bit of gameplay in Dave the Diver too closely, and you’re likely to find it lacking. Is a button mashing minigame really the most engaging way to reel in a fish? What am I doing during the Bancho Sushi segments except running left and right as quick as Dave’s little legs will carry him? Dave the Diver, like the Persona series, is a genre hybrid made up of simple yet diverse gameplay elements that combine to create something greater than the sum of its parts. When evaluated by its overall gameplay loop, Dave the Diver is an immensely satisfying game that’s tough to put down.

Dave the Diver takes place in and around an area called The Blue Hole — a real-life phenomena where a circular ocean cavern drops off near-vertically to sudden and insane depths. The game’s added twist to this is that the geography and ecology of its Blue Hole changes every time you enter it. This is the game’s way of saying “Hey! We’ve got Rogue-like elements!”. Every time you start a dive, you start from 0 — you go in with little to no equipment, and only keep whatever inventory of fish you manage to haul back. Run out of air and you lose that inventory.

The act of diving itself is one of the game’s many joys. Not only does the movement feel good in spite of being slow, but the simple act of exploring the sea life is rewarding. Despite their final fate as the ingredients of your sushi, The Blue Hole’s fish are lovingly rendered here. The respect that Mintrocket has for the ocean and marine life in general is abundantly clear. Sure, you’ll spend time doing plenty of goofy video game shit like blowing up schools of scad with mines or firing underwater rifles at tuna, but that always comes across as the need to put mechanics first. It’s the moments spent with seas turtles or saving a pink dolphin from a fishing net that will stick with you. It never gets heavy-handed — if anything, there’s some gentle ribbing of environmental absolutists — but it’s hard to leave Dave the Diver without feeling a greater appreciation for the ocean.

All of this would be for nothing if it wasn’t fun to spend time in the world of Dave the Diver. Thankfully this is one of the game’s greatest strengths. Not only is the Blue Hole a visual delight to behold — the pixel art is drop-dead gorgeous and the animations are so, so expressive — but the entire tone of the game is big silly. And in some really specific ways at that. Simple things like acquiring a new recipe or upgrading a sushi’s rank — things which could have been utterly mundane, menu-based events — become moments where Dave the Diver flexes its charmingly weird personality. You click “upgrade”, smash cut to Bancho wielding his Santoku Knife like it’s a Wakizashi, engaging in anime-style battle with what can only be assumed to be the fish themselves, his cuts so powerful that we jump to a wide-shot as the restaurant’s power goes out and waves resonate across the ocean — congrats, your level 3 Yellowfin Tuna sushi is now level 4. Call up Duff, a certifiable otaku who is to Dave what Otacon is to Solid Snake, and you’re “treated” to a montage of him sweating profusely, hard at work with a wrench, and smirking knowingly at a figure of his favorite anime character (a hybrid that can only be described as Gundam meets Sailor Moon) with a glint of light reflecting off his glasses — oh yeah, your new net gun is now crafted and hopefully sanitized. Later in the game, you’ll meet MC Sammy, a Korean rapper who appears alongside his hit track and your new favorite earworm: Hot Pepper Tuna. It’s way too well-produced of a track for how ridiculous the subject matter is — so it’s the perfect encapsulation of the game it’s featured in.

Sometimes, you need a game that isn’t too high stakes, one that can be played in short bursts and with the right type of vibe — sometimes you need something cozy. Dave the Diver is my choice for coziest game of 2023. Booting into its title screen and hearing the soft, rippling synth notes of its title track always felt like a warm hug. I played this game during a week where I was quite sick, and let me tell you — Dave and company were like chicken soup for my congested soul.

6. Amnesia: The Bunker – Frictional Games

It may not look like it, but this is actually the safest room in the entire game.

With Amnesia: The Bunker, Frictional Games has created what might be the closest thing to my ideal horror game. Its setup is a simple one: you are trapped in an underground bunker with something hunting you, there is only one exit, and you need to get out. It’s survival-horror distilled to its barest necessities — no high concepts here. But, as is the case with all minimalist premises, it is the specifics that really set Amnesia: The Bunker apart.

The first and most immediately obvious thing is that there are no objective markers telling you where to go, there’s no HUD, and there’s no real order in which you need to do things. Save for a brief prologue which serves as a basic tutorial of the game’s physics, combat, and healing systems, there’s never going to be any helpful text pop up when you get stuck, no tooltips to lend you a hand. Once the game proper begins and you awake — with amnesia, that old series canard — you’re left with only your wits and trial and error to figure out how things work.

If you’ve played any of Frictional Games’ prior work — their previous Amnesia games, the Penumbra series, or the criminally underrated Soma — you’ll know to expect unnerving atmosphere, top-notch sound design, and the constant cost-benefit analysis between when to hide in darkness and when to seek out the nearest light source in moth-like fashion. That’s all still present in The Bunker, and done remarkably well, but what you might not expect is how all of this is laid atop a new design philosophy that emphasizes non-linearity, procedural gameplay elements, and replayability. The Bunker is far and away the shortest game I played all year — and capable of being really, really short if you know exactly what to do — but is designed around being played more than once. When you start a new run, the game seeds puzzle solutions, locker codes, and loot placement unique to your playthrough. The game world itself is still fixed, and the story is going to play out the same each time, but you aren’t going to be sequence breaking the game by trying 0451 at every padlock or Googling the answers either.

That said, the entity with the most unpredictability in the game is the monster itself. The Bunker’s sole enemy is not a scripted threat that appears only when the developers want it to, but rather a dynamic AI that responds to changes in its environment. Sprint too loudly or fire a weapon, and the creature is bound to emerge from the nearest hole in the wall to begin investigating. It’s oppressive, as practically everything you do creates some sound — your hand-cranked flashlight being one of the absolute noisiest, in true double-edged sword fashion — and therefore even lighting up a hallway has some chance of getting you torn apart. But attentive players will eventually learn how to exploit this behavior, creating intentional noise as a distraction while they carry out an objective.

Another thing you’ll find out rather quickly is that the monster prowling the concrete halls of the bunker loves to hunt in total darkness. And wouldn’t you know it, the fuel supply for the generator is completely exhausted at the game’s start. So long as it remains that way, you will make for easy prey — fumbling and near-blind in the dark. It’s only when the generator is running, powering the few electrical light sources remaining in the bunker, that you will have some reasonable reprieve from the creature. To keep the generator operational, you will need to seek out half-empty jerry cans from around the bunker, ferrying them all the way back to the central Officer Hub where you can refill the fuel tank. The game generously offers you a pocket watch that you can sync up with the generator, giving you the means to predict roughly how much time is left before lights out. Not so generously, that pocket watch takes up space in your preciously limited inventory, so you’ll need to weigh your options and decide how valuable that knowledge really is to you. Decisions, decisions.

The center of the Officer Hub also functions as your Safe Room, as you’ll be returning here frequently to keep ol’ Genny purring. It’s the only room in the game with a full map of the bunker, and also the only room with a dedicated item box where you can stash extra supplies. Oh, and perhaps most importantly, it’s the only room where you can save the game. Yes, this is an Amnesia game that takes clear inspiration from the likes of Alien: Isolation and old-school Resident Evil. Get killed, and you’ll find yourself returned all the way to home base. You’ll want to plan each excursion carefully — study the map, check your inventory space, and reload your gun. The longer you spend exploring away from the Officer Hub, the greater the tension ratchets up.

And yeah, I kinda buried the lead there, but this is the first Amnesia game to feature honest-to-goodness weapons. Not only is there a pistol, but you can also find hand grenades and craft improvised Molotov cocktails. For all the good they’ll do you, anyway. As you probably guessed by now, the monster isn’t something you can kill, no matter how much newfound firepower you have on hand. You’ll only want to use these things in combat as a last resort. Instead, think of your arsenal of weapons as tools to solve problems. If a door is padlocked shut and you can’t find an alternate route inside, why not shoot the lock off? Need a distraction, and an incredibly loud one at that? That hand grenade will definitely get the creature’s attention. Flesh eating trench rats blocking your path? Introduce them to some Soviet-era mixology and they’ll move.

These are all just suggestions, mind you. The game never explicitly tells you what your tools are meant for. Instead, you should feel free to get creative and experiment, as there is rarely one solution to any given problem. Early on in my playthrough, for example, I came across the “Mission Storage” room. I really wanted to get into this room, but the doors were locked. My solution to this problem ended up being to drag a canister of gas from the next hallway over and to shoot it, exploding the door along with it. What I didn’t realize at the time, is that I didn’t need to spend a bullet on this task. Instead, if you find a heavy enough throwable object, you can hurl it at the door a few times, and it will eventually break. A slower and still noisy process, but it doesn’t cost you anything. You could also just throw a grenade at the door if you happen to have one, but this is a particularly wasteful move unless you need to move fast. It wasn’t until after I had entered the room and looted what I could from it, that I discovered — in a face-palm moment — an air duct that I could have simply crawled through to get inside. I’m almost certain that was the intended way of getting in, but I like that the game allowed for all of these different options, even if I later realized I hadn’t picked the optimal one.

It’s not Earth-shattering by any means, but it’s a welcome bit of improvisational gameplay for the survival horror genre in particular — a genre perhaps best defined by ultra-specific puzzles with singular key items being required to progress. Here, instead, almost all of the game’s already limited resources have dual — if not triple — purposes, and figuring out how to use them in addition to the typical where and when creates an interesting dynamic.

The original Amnesia came out at a time when survival horror was increasingly taking a backseat to action horror. At the time, in 2010, the idea of a horror game where you couldn’t fight back — you could only run or hide from threats — was a radical one. Twitch was still getting more popular around that time too, and the streaming platform helped bolster the impact of the game to a much wider audience. It went on to influence a decade-long renaissance of the genre — you can see its fingerprints on nearly all of the scariest games released in the 2010s, from Outlast to Alien Isolation to Resident Evil 7 and even the infamous P.T. from Hideo Kojima himself. Not to mention a few hundred dime-a-dozen indie horror games on Steam, nearly all of which owe some small debt to Frictional’s particular style of horror. In a lot of ways, The Bunker represents Frictional finally cashing in on that debt, this time doing a little borrowing of its own. The result is all the better for it — The Bunker is a far-cry from the dull affair that was 2020’s Rebirth — yet it doesn’t feel like this is Frictional surrendering to industry trends either. Instead, The Bunker manages to integrate all of these new ideas into something that is remarkably cohesive. It may be a short game, but The Bunker is easily one of the most memorable experiences I had this year.

5. Alan Wake 2 – Remedy Entertainment

Once Alan finishes his latest blog post, it’s over for you bitches.

If Control was the point that Remedy finally let their freak flag fly in true unapologetic fashion, Alan Wake 2 sees them operating with a renewed confidence in themselves, creatively unshackled from petty worries of whether or not “this is all too weird for people”. Ever since they’ve let loose in this way, they’ve won me over completely to their eclectic approach to game design. Alan Wake 2 is my favorite game they’ve yet made, and it has me excited for where things might go in the future.

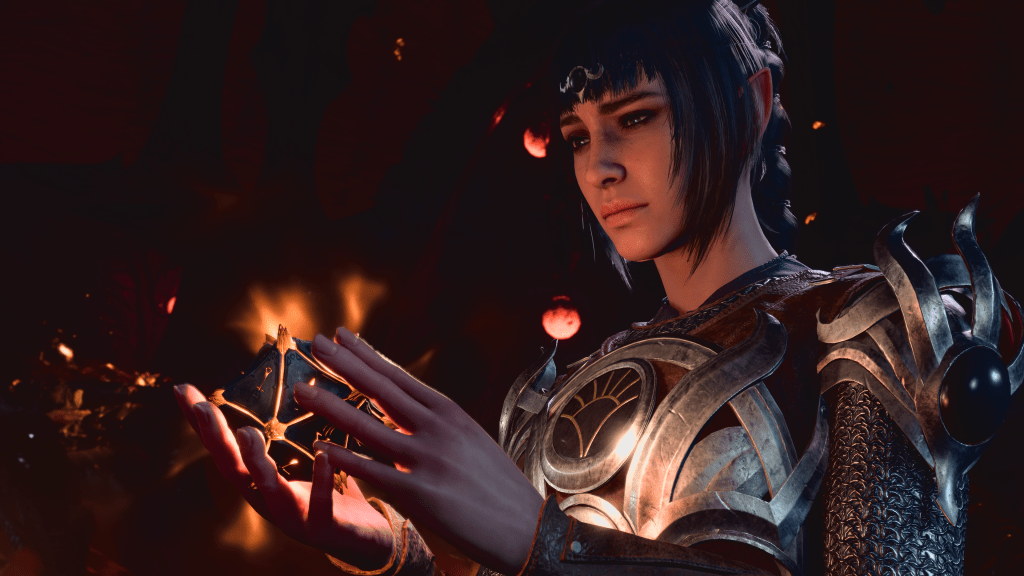

Alan Wake II, in keeping with the real-life passage of time, takes place 13 years after the events of the first game. A series of mysterious murders has been happening, the most recent of which occurred off the shore of Cauldron Lake in Bright Falls. This latest victim has had his heart cut out in some sort of ritual. You play as FBI agent Saga Anderson, who is dispatched with her partner Alex Casey to investigate. After your first day of investigating, you determine that these rituals have been carried out by a group calling themselves The Cult of the Tree, but also that something otherwordly has been going on in Bright Falls. Whatever this is, it clearly has to do with Alan Wake, the writer who disappeared near Cauldron Lake 13 years ago.

But the real mystery at the heart of Alan Wake 2 isn’t the cult’s motives or what happened to all their victims. No, the real mystery that eventually takes form is who exactly Saga Anderson is, what her relationship to Bright Falls is, and what does any of that have to do with Alan’s own story struggling within the Dark Place? There is no big, singular expository moment that reveals all of these things directly, and even if I told you here it wouldn’t do it justice. Alan Wake 2 takes the stance that how you present the story is just as important as the story itself, and I couldn’t agree more. I love the slow-burn way the mystery unspools, opting for high concept situations and scenes to parse out information and detail rather than relying on some info-dump “reveal”. Some elements are only confirmed indirectly — others still, strongly implied — in such a way that you can tell the creators at Remedy have faith in their audience to piece things together for themselves.

One of the things that always bothered me about the original Alan Wake was that, despite being inspired by and paying homage to the TV series Twin Peaks, the comparison always felt rather thin. There was more to Twin Peaks than being an eclectic murder mystery situated in the piney Pacific Northwest. Twin Peaks was also a highly experimental series — impossibly so by modern standards, given its status as a network show on ABC of all places. Its twists and turns played with the format of the television medium just as much as they offered strange tonal dichotomies and bizarre non sequiturs. Not so with the first Alan Wake — a game which, despite its lofty narrative ambitions, played as a fairly straightforward action game with traditional enemy types, progression, and gunplay. The flashlight mechanics offered enough support structure to prop up the gameplay and keep the experience novel, but even that got shaky by the game’s final hours.

Alan Wake 2, by contrast, is zealous in all the ways it plays with the form. Remedy experiments with everything from the design of levels and the physical space they occupy to the way enemies spawn in and begin pursuing the player. They allow the player to change the atmosphere of certain rooms on-the-fly as they attempt to “rewrite” their reality, and allow the player to enter an abstract, cerebral space at will in the form of Saga’s “Mind Place” or Alan’s “Writer’s Room”. They even toy with the structure of the game itself, breaking everything into separate campaigns — Saga and Alan — that intersect at various points and can be experienced in either order. All the while, these dueling stories play with expectations around the timeline in ways that deepen the mystery further. The comparison to Twin Peaks feels much more apt now, and the Showtime 3rd season revival seems like the much more clear inspiration.

I can’t just gloss over this game’s technical achievements either. A really depressing industry trend we’ve seen over the last few years is the slow consolidation of game engines around a handful of market leaders to the detriment of custom, in-house solutions. The chief winner in all of this is of course Epic — with a long list of studios and publishers rallying behind Unreal Engine 5 as the toolset-of-choice for next-gen game releases. There are pros and cons to this, but I would argue that one of the biggest drawbacks for gamers is a reduction in the range of visual variety we see out of AAA studios, as more and more forgo specialized software solutions for their projects. Case in point for my argument is Remedy’s Northlight Engine, which powers the visuals of Alan Wake 2. The results really speak for themselves here, but this game has some of the best lighting of anything out there. If you’re fortunate enough to experience this game on a PC capable of maxing out its various ray-tracing settings, I highly recommend it. The results are tremendous. This is one of the best and most unique looking games I’ve ever seen, with bar-none the best indirect lighting and volumetric fog, all of which contributes towards the game’s thicc-with-two-Cs level of atmosphere. Not only that, but the engine enables Remedy to integrate live action FMV directly overtop of traditional rendered scenes, and it gets leveraged for all sorts of uses — including some of the game’s biggest scares. I, for one, am very pleased that the engineers at Remedy are still doing their own thing. No bullshit — they are true masters of their craft.

Nowhere is this technical prowess more keenly felt than in third chapter of Alan’s story, dubbed simply “We Sing”. Without giving away too much, this chapter feels like the culmination of just about everything Remedy is know for — gameplay set to a bombastic musical number, live action FMV integrated seamlessly alongside the in-game models, plus excellent usage of stage direction and lighting to keep the player clear on exactly which direction to go. It’s a sequence that goes on longer than you’d ever imagine it might, and to great effect. It’s joyously over-the-top and effortlessly masterful in equal measure, and quite possibly the highlight of the entire game. Definitely something that needs to be seen to be believed, and ideally interacted directly with and not just watched online. If this were a list of “moments of the year”, this would be at the top. I don’t know if another developer would have even thought to do something like this, and — even if they had — they wouldn’t have done it as well as Remedy.

What shocked me most about Alan Wake 2 wasn’t it’s jaw-dropping visual fidelity, weird-as-fuck story machinations, or even its heavy use of live-action FMVs for key moments. I sort of expected all of that. After all, this is a Remedy game we’re talking about. No, what surprised me most was the way the game borrowed core elements of its design from old-school survival horror games. The developers had been pitching this game from early on as a survival horror game — in contrast to the more action-focused original — and it’s great to see that it wasn’t mere lip service. The game is indeed tighter on resources, lighter on combat, and much, much creepier.

You can certainly feel the influence of the recent Resident Evil remakes at work here — the game shamelessly lifts the block-based inventory, quick slot weapon selection, and item boxes from 2019’s RE2 — but beyond that, one key influence stands out: Silent Hill. You can see its fingerprints all over this game’s locales and concepts: Creepy amusement parks? Check. Everyday locations twisted into haunting facsimiles of themselves? Big check. Freaky, possibly-Satantic cults with a penchant for ritualistic sacrifice? Triple check. Not only that, but each area of the game requires you to find an in-world map which your character begins marking up and annotating with details as you explore — jotting quick notes, scratching out dead-ends, or flagging various points of interest after you’ve seen them. If you’re as old as me, that’ll sound familiar. Not to mention the atmosphere of the game feels eerily familiar to those early Team Silent games. Oftentimes you’re wading through fog-laden streets or getting twisted around in dream-logic corridors that crisscross the level in impossible M.C. Escher angles. To put it in the simplest terms I know how: it fucking rocks.

Perhaps the most ambitious element of Alan Wake 2, however, is the way in which it attempts to stitch all of the Sam Lake-written Remedy games into a singular, cohesive universe. And sure, we live in the era of the multiverse narrative — whether that’s multimillion, multinational, multiplex-busting mega movies mimicking the Marvel format or heart-on-its-sleeve, off-the-wall, award-winning films like “Everything Everywhere All At Once” — but I don’t think I’ve seen anyone do the whole crossover concept with quite the degree of specificity or self-referential craziness that Remedy achieved here. I’m now going to attempt the ill-advised task of trying to explain it.

Let’s take just one example. Otherwise we might be here all day. Alex Casey, the FBI agent partner of Saga Anderson, shares his name with the character Alex Casey, from Alan Wake’s popular series of crime novels. He mentions offhandedly at the beginning of the game that he doesn’t appreciate the jokes he always gets, comparing the two of them for sharing the same name. That said, observant Remedy fans will recognize Alex Casey — the FBI agent — immediately, and for two big reasons. Not only is Alex Casey’s face modeled by none other than Sam Lake himself, but he’s also voiced by none other than James McCaffrey — who sadly passed away on December 17th of 2023. In other words, Alex Casey doesn’t just share a namesake with one of Alan Wake’s creations — he shares the same face and same voice as Max Payne himself.