I feel like 2022 was a better year for just about everyone than 2021. The future is still uncertain, but things look brighter at this time than they did a year ago.

That said, this year was a bit of an awkward one for the games industry. Lots of delays of games into 2023. Lots of big anticipated titles that felt disappointing. This happens a lot during the first year of a new generation of consoles, as the industry looks to reset as it adopts new technology. That should have happened last year, as more PS5s and Xbox Series X/S consoles got into people’s hands. Instead, this generation has had a bit of a slow start, with lots of cross-generation stuff still hanging around. 2023 will probably be the year where this finally starts to shift, but until then we have a bit of a lethargic year for game releases that feels a lot more like 2014 did than 2015.

All that said, let’s get into my personal favorite games of the year.

Real quick, before I get into it –

Quick obligatory notes:

- This is a ranked Top 10 list with 3 honorable mentions (unranked).

- Each game features a link to one of my favorite pieces of music from its soundtrack. Feel free to listen as you read.

- I consider the release timing of Early Access games based on when they exit Early Access, or enter V1.0.

- Remakes (which are becoming even more common these days) can be on my lists, but only if they are substantial enough in that the game is something fundamentally different. Examples of games I counted in 2019 were Pathologic 2 or Resident Evil 2. In 2020, I didn’t consider a game like Demon’s Souls (even though I loved it) because it is mostly a visual overhaul to the 2009 original game. Hopefully that distinction makes sense and isn’t just arbitrary to you.

- I’m never able to get to all the games I’d like to by the end of the year. There are always ones that slip through the cracks. I typically like to list up front the games that I had the most interest in that I admittedly didn’t have time to get to. This year, my pile of shame is as follows:

Pile of Shame:

- Mario + Rabbids Sparks of Hope

- Splatoon 3

- Sonic Frontiers

- I Was a Teenage Exocolonist

- Neon White

Okay, with that out of the way, on to the list…

Honorable Mentions:

Warhammer 40,000: Darktide – Fatshark

It’s difficult to talk about Darktide without drawing direct comparisons to Vermintide 2 – which is probably my favorite co-op game of the last half decade or more. In fact it’s probably inevitable to draw comparisons. So, that being said, let’s start with the good stuff.

Darktide’s combat feels significantly improved. The outrageously devastating and comically oversized weapons of the 40K universe are an absolute joy to wield when compared to Vermintide’s meager ranged options. For my first character, I played as an Ogryn, 40K’s race of towering mutant humans. When playing an Ogryn, the first weapon you’re presented with is the Lorenz Mk V Kickback, which, as the name suggests, is a less a shotgun than it is a type of buckshot cannon that you can carry around with you. Everything from the sound design to the enemy stagger to the gibbing animations make firing a single shot from this thing feel absolutely massive. I knew as soon as I used it that it was positive sign for the weapons to come, and sure enough, the game’s arsenal continued to impress as I played. Every shooter worth its salt needs a good shotgun, right?

The game’s technical prowess also represents a significant step up from its spiritual predecessor. The environments of Darktide – which is set on the planet Tertium – positively ooze atmosphere and detail from every square inch. The way that game utilizes volumetric light, fog, and material-based rendering creates what is undoubtedly the most complete depiction of the 40K universe out there. How Fatshark manages to get such impressive visuals out of its in-house engine (Bitsquid, now Autodesk Stringray) continues to blow me away. Is it performant? Well, not exactly. The sheer scale of Darktide’s plague-afflicted hordes will reduce all but the absolute latest PCs to a stuttering mess. But regardless, these are visuals that truly feel “next-gen”, coming at a time where game graphics appear to be stuck, rife with cross-gen compromises. It’s exciting to play a game that feels like it’s actually doing something with all that expensive hardware, not just pushing framerates into the stratosphere.

Unfortunately, as is the case for a lot of live-service games still in their infancy, Darktide feels incomplete. The same maps come up in rotation far too frequently, and many of hub’s features – shops, training areas, etc. – feel half-baked or even unfinished. The issue with maps has to do with how Fatshark chose to structure Darktide’s content. Where Vermintide 2 at launch was divided into 3 distinct campaigns that proceeded from one locale to the next in a logical progression, Darktide instead ferries its players to and from each mission on dropships. There’s no real story to speak of, and instead, each of the game’s 14 maps are explicitly categorized as one of 7 possible objective types: Raid, Assassination, Strike, Espionage, Repair, Disruption, or Investigation. It all feels a bit hollow structurally – launch map, play whatever mini-game that the objective type told you that you would be doing ahead of time, reach the extraction point, repeat – but that might just be down to my personal taste.

What really hurts, however, is that there is currently no way to select a given map and difficulty to play at-will. Instead, the mission select is handled in a manner similar to Deep Rock Galactic, where a handful of randomized mission options will appear on a quest board until a real-time timer expires, at which the game will roll a new map and difficulty. That type of approach works fine for a game like Deep Rock, where every mission is procedurally generated to one degree or another, but I found it absolutely baffling for a game like Darktide. You might arrive back at the hub with your friends to find that the only fresh maps available are at the mind-numbingly easy 1 and 2 star difficulty levels, while the harder missions are all retreads of the same area you’ve done 3 times over already. Yes, you can select a specific difficulty for Quickplay, but that selects a random map and might join you to a mission midway through. Not only that, but the weapon shop in the game works much the same way. Since the loot available in the shop is randomly generated, there are times when you’ll scrub through the list only to find that you have nothing worth saving your money for at the moment. The shop resets every real-time hour, so you basically end up checking it between every mission to see if anything the algorithm chose to generate is even worth a shit. It’s a really tedious progression loop, and it undermines what is otherwise a brilliant co-op experience.

So, is Darktide as good a game as Vermintide 2 was? Well, no, obviously it isn’t. At least not yet. Given the long support window that Vermintide benefitted from however, it might still be too early to make that call. It goes without saying though, when shit kicks off on a high intensity zone, with hundreds of enemies pouring out of every nook and cranny of the environment, and your whole team responds in-kind with grenade explosions, psychic cranial explosions, jets of red-hot flame, and massive cleaving swings of a man-sized bowie knives…no game this year quite reaches the levels of insanity that Darktide is capable of in these moments. It’s for this reason that Darktide makes this list, but there’s certainly room for improvement here.

God of War Ragnarök – Santa Monica Studio

It’s almost impossible to deny that God of War: Ragnarok is one of the most well-made games of 2022. It’s ridiculously polished, to the point that custom dialog is written for nearly every point in its story that you decide to take a sidequesting detour. I wondered, when taking an entirely different companion with me to free the second Halfgufa in Alfheim’s desert, whether Kratos and company would have as much character arc-specific conversation about its imprisonment. Indeed they did. When I would struggle a bit too long with a puzzle, the game would swiftly step in, offering increasingly leading hints via companion dialog, afraid that I might put the game down if I got stuck for too many minutes. Every moment has been carefully accounted for, play-tested extremely thoroughly, and every rough edge has been buffed down ensure a smooth experience.

At times this can feel stifling, constantly being shepherded toward progression when you just want to figure things out for yourself. At times all that custom, carefully constructed dialog gets in the way, when all you want is to explore in silence without worry of missing some new character beat. At its best though, this new God of War is a joy to explore, its level design just complex enough to reward your curiosity without derailing into aimless wandering. Its puzzles are rewarding to solve, always ensuring you get some interesting item for your time spent scouring its environments for Nornir chest runes. And this is to say nothing of the game’s combat, which – as expected – is just as deeply satisfying as ever. Recalling the Leviathan Axe to Kratos’ hand and feeling the haptic bump of the controller against your palms still stands as one of the fastest paths to dopamine release in a single gameplay loop. When the game allows you to let loose as Kratos, swapping between the ice attacks of his axe and the flame of his Blades of Chaos, I always had a great time with it. The boss fights are all well-designed and look great in action, especially an early-game one that echoes Kratos’ encounter with Baldur from the last game. There’s a couple of optional boss fights in the end-game that are exceptionally difficult in an unfair way, and really make obvious the limitations of the combat design, but those are exceptions rather than the rule.

And despite all of the hand-holding that I bemoaned earlier, there’s a great section in the final hours of Ragnarok where it opens up substantially. Hidden behind a single optional sidequest in Vanaheim is a gigantic secret area that itself spans at least a dozen more sidequests, all arranged around one of the most visually interesting and freeform maps in the game. It’s absolutely the best part of the game, and as exhilarating as discovering it was, it also does beg an unfortunate question – why wasn’t the rest of the game like this?

If it isn’t obvious yet, as much fun as I had with it, I’m torn on God of War: Ragnarok. While the 2018 God of War remains one of my favorite games of the last half-decade, razor-focused in what it wanted to achieve, this sequel feels totally adrift by comparison. There are plenty of great individual moments throughout Ragnarok, but very little in the way of thematic glue to bind them all together. I appreciate that Santa Monica Studio didn’t feel the need to create an entire trilogy of games, opting instead to resolve Kratos’ time in Norse mythology in just two parts. But given how all over the place the story is here, how big and overwrought the plot is, maybe it would have been better to go the traditional trilogy route. The pacing is really awkward, and attempts to break up the normal gameplay loop with Atreus-led bow and arrow shooting sections feel forced and above all, boring.

And none of this is to mention my biggest issue with the game, which is the Joss Whedon-ization of so much of the dialog. So many characters in Ragnarok all communicate in Marvel-speak – the kind of detached, ironic, trying-so-desperately-hard-to-be-relatable, self-aware jokesterism that has become the de-facto standard for how to write characters for blockbuster entertainment – that they all started to blur together in my head. When practically half of the cast are competing to be the comedic relief, it becomes difficult to take any of them seriously when the actual drama begins to kick off. I found myself getting tonal whiplash constantly, never knowing when I was supposed to be getting invested or really why I should. The 2018 God of War had such a strong, distinct tone – something so many AAA games struggle to achieve – but Ragnarok can’t seem to decide what it wants to be – an operatic familial drama or a Thor Ragnarok impersonator.

It’s a shame that Sony’s first party output, which has been the envy of the entire industry over the last generation of consoles, has seemed to struggle so much with creating worthy follow-ups to its beloved first acts. Recently, we’ve seen them fumble the sequel to The Last of Us – an ultra-violent, ultra-grim but ultimately poorly characterized and patronizingly didactic story – as well as the Guerilla Games epic Horizon Forbidden West – a game from this year with absolute top-tier technical prowess but insufferably long-winded characters and a shockingly stilted combat system. To be completely clear: I think God of War Ragnarok is a better game than either of those other two. I had a lot of fun with it, even to the point that I got a 100% completion rating. But this game should have been in contention for placement a lot higher up my list. So, while this is an extremely polished game with excellent voice acting, gorgeous environments, satisfying combat, clever puzzles, and solid level design, it never rises above the sum of its parts.

When you’re the follow-up to 2018’s God of War, being a really good game doesn’t quite cut it for me. You must be better.

Kirby and the Forgotten Land – HAL Laboratory

I’ve never been much of a Kirby fan. Actually, let me rephrase that: I’ve never played a Kirby game. At least, not until I picked up Kirby and the Forgotten Land this year. Now, having introduced myself to the series with such an impeccably designed game as this one, color me freshly converted. I am a new disciple to the Church of Kirby.

Kirby and the Forgotten Land is pure level design. Using scripted camera angles most reminiscent of Super Mario 3D Land, it showcases its 3D world with just the right framing at the right moment. There’s no fighting the camera in this action platformer, so you get to focus all of your attention on controlling Kirby.

There’s such playfulness in every aspect of this game, from the world and enemy design to the quirky challenges it presents the player with. One level might have you rounding up a brood of baby ducklings and returning them to their mother. Another might have you grabbing the Sleep copy ability to take a nap poolside. Then there’s the new Mouthful Mode feature, which is what happens when Kirby tries sucking in inanimate objects multiple times its body size – be them vending machines, giant traffic cones, an entire set of stairs, or a rusted-out car. Each one of these objects enables Kirby to significantly transform the gameplay at a moment’s notice. Kirby can become a hang-glider for a flight sequence, swallow a lightbulb whole to illuminate platforms in the dark, or just completely inflate with water to spray away some unsightly sludge – all that’s missing is some of that sweet Delfino Plaza music. Needless to say, the chaotic energy of Kirby sucking in an entire car and then driving it around, boosting into enemies, is funny every single time you do it.

The Mouthful mechanic, combined with the series staple ability for Kirby to absorb enemies and copy their moveset, makes for a game which changes up its gameplay like Fortnite changes up its corporate partnerships. It reminds me of Cappy in Super Mario Odyssey, and how that game would theme entire sections around a given transformation. In much the same way, Forgotten Land makes excellent use of Kirby’s copy ability, crafting levels around the various powers. You might have ice blocks that need melting with Fire Kirby, faraway platforms that need Tornado Kirby’s ability to float to them, or bullseye targets that require that Ranger Kirby bust out his guns.

Outside of the main levels, the game also features what it calls Treasure Road maps, which are optional time trials centered around a particular transformation. Completing these will grant you Rare Stones that can be spent to upgrade your copy abilities. Completing the Treasure Roads is rarely challenging, but achieving the target times it asks of you can require near perfect movement. In doing so, it feels in keeping with the way modern Nintendo games have been handling difficulty curves for several years now: the game is easy to complete, yet quite challenging to master if you want to 100% it.

Kirby and the Forgotten Land represents Kirby’s first foray into a fully 3D game world (though there are some edge cases that may or may not count to you). It’s not some groundbreaking entry into the 3rd dimension, the way that the Mario or Zelda or Metroid franchises had, but it is a fantastically well-made game nonetheless. Sometimes a game is just a fun time, and doesn’t feel the need to reinvent the wheel too much. That’s exactly how I would describe Kirby and the Forgotten Land.

Top 10:

10. Cult of the Lamb – Massive Monster

In playing Cult of the Lamb, I learned a lot about running a cult. The key takeaways are these: it’s very important, after giving your daily sermon, to ensure you clean and sanitize your followers’ nasty-ass living space of vomit and poop, always enter into a one-sided polycule by marrying as many disciples as possible, and remember to extract maximum tithes from your flock – these little fuckers weren’t doing anything with the money anyway.

Cult of the Lamb is perhaps the most Delvolver-ass Devolver game yet made. An off-kilter rogue-lite with gorgeous 2.5D art, a wicked sense of humor, and a kickass soundtrack positively stuffed with bangers? It checks all the boxes, for sure.

To get a bit more specific, Cult of the Lamb is a mashup of 2 distinct halves. The first is the rogue-like dungeon crawling component, where you as the titular Lamb fight your way through randomized dungeon rooms, selecting your own path through a map until you reach the area’s final boss. Each zone is demarcated on the map based on what it contains – it could be base resources like wood or stone, followers to be recruited to your cult, or simply combat encounters with enemies. When it comes to combat, you have 2 distinct weapon slots – a physical melee weapon and a magic ranged spell. You can opt for a simple sword with a 3-hit combo and solid reach, or a much more strength-build type of approach with a hammer that hits for massive damage but has no combo potential. There’s a variety of ranged spells that are similarly balanced around situational advantages. There’s also a dodge move. It’s pretty par-for-the-course stuff for a modern Rogue-like, and so if you vibe with that type of combat, you’ll likely enjoy Lamb’s as well.

The game pairs this dungeon crawling Rogue-like gameplay loop with a fully fleshed out base building mechanic. It’s here that Cult of the Lamb gets to flex its personality a lot more. Your flock of followers are a gaggle of grinning anthropomorphized animals, fish, and satanic horned demons that toil and pray for you all day, taking only short breaks for sleep at night. You can put them to work harvesting resources or building structures or planting crops and fertilizing them with the excrement of their fellow true believers. They level up as they serve you, and it’s up to you whether you sacrifice your most experienced flock-members for XP or let them reach the end of their housefly-eque lifespans naturally. But even in death their bodies can still serve their dear lamb – they can be processed into fertilizer or turned into an inconspicuous meal for their oblivious flock-mates.

Real quick though, I need to take a moment to talk about Cult of the Lamb’s soundtrack, created by River Boy, the solo act of Australian electronic music duo Willow Beats. Its sound is wholly unique and seriously fucking cool. One part saccharine cartoon chanting and one part trip-hop make for some shockingly catchy earworms. Don’t believe me? Go ahead and put on the track “Sacrifice”. Go on, I’ve got time. Actually, wait. Fuck. You should play “Work and Worship”. That’s the one. But be sure to check out “Start a Cult” and “Eligos” while you’re at it.

Cult of the Lamb isn’t perfect. The combat feels a bit too simplistic compared to recent entries in the rogue-like genre. The Tarot card mechanic, which serves as the game’s buff/modifier system, generally works well but stops short of going truly deep. The connective tissue between the dungeon crawling and base building could be stronger; as it is you get these brief notifications while out exploring that someone or another died, got sick, is rebelling, etc., which feels a bit like an afterthought since you can’t do much with that info except think “Dang, RIP”.

All that said, I will say that Cult of the Lamb is a perfect Halloween game. It fully occupied my October of 2022, hitting just the right balance between spooky shit and adorable shit. And even though I think there’s room for improvement, the gameplay loop is addictive enough that I had trouble putting it down. It’s easily one of the most stylish games of 2022, and its dark Happy Tree Friends-esque humor really sets it apart in the currently popping off Rogue-like genre.

Just remember: it’s a cult, not a commune, so don’t be afraid to cull the herd from time to time. Their sacrifice will be worth it.

9. NORCO – Geography of Robots

The world of Norco, based on its real-world counterpart outside New Orleans, is a listless one. The petroleum companies have long since extracted the value from under the earth here, leaving in their wake an irreversibly decimated environment, a series of continual floods, and illness that the human populace must contend with. Many of the people here have long since fled the area. The people who remain aimlessly drift around, doing things to survive or find meaning, but without much concern as to why. They take up gig-worker jobs, letting apps send them on wild goose chases for cryptocurrency payments that might be lucrative one day and completely valueless the next. Young boys fall into cults, more-so to feel belonging to something larger than themselves, and less-so because of any real belief in what they’re doing. Guys in bars talk about starting news blogs on their own to “expose the truth” about what’s happening around town, but without any real focus or sense of injustice other than a commitment to a vague “the people gotta know” sentiment.

The fantastical, Southern Gothic imagery paired with this malaise creates a beautiful contrast – a sign that, in some alternate universe, things didn’t have to turn out this way. There’s still beauty here, among the marshland and the people, in spite of the fire-belching refineries looming over the landscape.

There’s science fiction concepts at work in this world – robot assistants, AI, brain scans, uploading of one’s consciousness to computer networks – but all of them applied in completely banal ways. The AI is put to work running the register at the equivalent of a 7-Eleven. The brain scans have been subsumed into the greater American health insurance industry, completely privatized and mundane. Robots largely fill security roles, protecting private property for corporate interests. There is no hope for the future of humanity to be found in technology. Instead, technology only latches on to the existing dysfunctions of society, hyper-accelerating them to the detriment of many and to the benefit of the usual suspects. Sound familiar?

Norco is a text-based adventure game that casts you in the role of Kay, a woman who fled the Norco area when she was younger, leaving her mother and brother behind. At the game’s outset, Kay is returning home after receiving word that her mother has died. Upon returning home, she realizes that her brother has been missing for days. He’s been sighted at a local bar, but no one has seen him since then. Accompanied by her mother’s robot assistant Million, Kay sets out to find her brother and uncover some of the dark secrets of the town’s refining company in the process.

When I initially finished Norco, I was left feeling somewhat cold by it. At practically every junction, the game avoids making prescriptions for the issues it deals in. Instead, Norco is decidedly observational in nature. It is satirical, sympathetic, and melancholy in an aesthetic sense, but it poses no real solutions, declares no real enemies. There’s a purity in this, because the game doesn’t pretend to be arrogant enough to have all the answers to society’s problems. However, there’s also something that rubs me the wrong way about it.

As it progresses, the focus of Norco’s narrative increasingly becomes wrapped up in religious allegory. Holy symbols and questions of faith begin taking center stage as any sort of commentary on class or societal ills begins to fall to the wayside. I feel this will either carry a lot of weight for you personally or it will leave you feeling somewhat ambivalent, as it did me. That said, there’s so much humanity packed into the game and its characters that I still found the story compelling even as it took a thematic left-turn in its latter half.

The industry needs more games like Norco. Extremely personal to its creators and hyper-specific in its focus, it never sets out to please everyone that could conceivably pick it up. Norco might not go in exactly the direction you expect or even want it to, but you also haven’t played anything else quite like it. There are comparisons to be made to Kentucky Route Zero or Night in the Woods, games with localized narratives, a focus on regular people rather than explicit heroes or wealthy people of import, and whip-smart senses of humor, but each of these are so different in execution and thematic content that they need to be taken for what they are.

In an observational capacity, Norco is beautiful, hilarious, and captures the totalizing ennui that is American life in this particular moment. Its cast of characters spans the gamut between quirky and outright strange, and it’s hard to forget any one of them. The pixel-art that makes up the various screens of the game are absolutely gorgeous and I looked forward to each time I progressed to a new area. The music is packed with feelings of nostalgia and sadness and yearning. The setting is distinct and its mirroring of the real world as well as real events hit at some very raw emotional nerves for me.

In these ways, Norco is a fantastic game. Is it an important game though? That’s up to you to decide for yourself.

8. The Quarry – Supermassive Games

Woman: *runs headfirst into the plot*

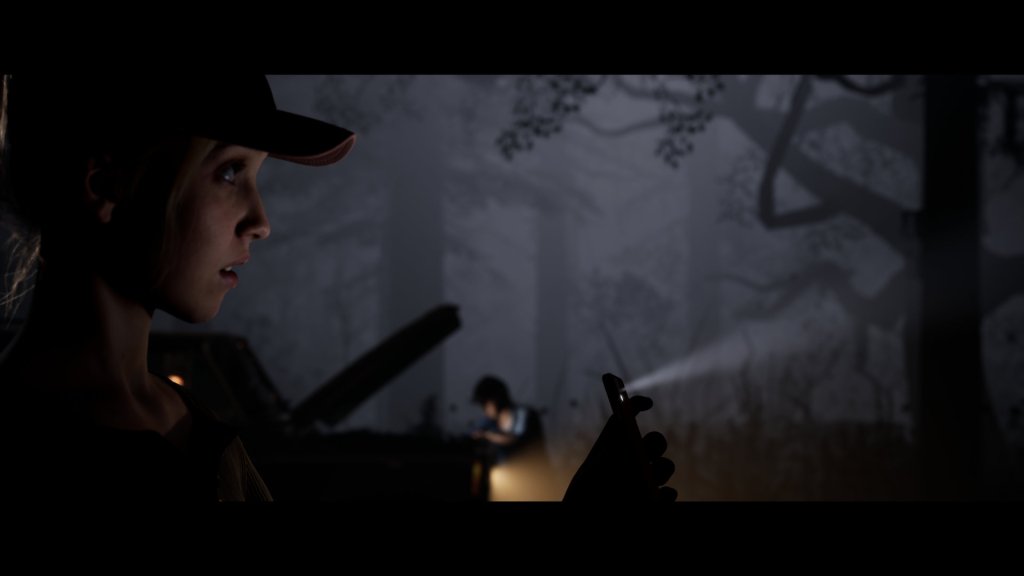

Say what you will, Supermassive Games sure knows how to hit their deadlines. The England-based developer, which achieved mainstream notoriety with their 2015 teen slasher creature feature Until Dawn, has been on a tear as of late, putting out a new entry in their Dark Pictures Anthology series every Halloween season. This year was no exception, as they released The Devil in Me, a Dark Pictures game set in a Murder Castle based on real-life serial killer H.H. Holmes. But despite its ambitions to change up the Supermassive horror formula, I found that particular game pretty disappointing. Not so however with Supermassive’s completely out-of-nowhere surprise summer release: The Quarry.

The Quarry, in many ways, feels like Supermassive getting back to its roots. Firstly, though it is set in decidedly modern times – complete with smartphones and live streams – the game pulls from an amalgam of 1980s teen slasher films, namely Friday the 13th, Sleepaway Camp, and The Evil Dead. It is set in Hackett’s Quarry Summer Camp, with the player controlling the 8 camp counselors on the last day of camp. It’s a simple setup and something that’s become a bit of trope in horror, but it’s this cast of characters really sets this story apart and makes it unique.

Supermassive’s writing has never been poor per se, but the developer has struggled over the years with crafting characters that are believable, likeable, or fun-to-hate. Prior to now, Until Dawn was probably the closest they got, and even that game had some pretty questionable moments of awkward dialog. With The Quarry, Supermassive has created far and away their most memorable cast of characters. The dialog is much more convincing at nailing the mannerisms and attitudes of teens in the middle of transitioning to adulthood. Not only that, but the acting is so much more natural. The actors bounce off each other’s performances and feel more like they are playing their characters than reading dialog word for word from a script.

These games live and die by the choices they ask you as the player to make. This is where The Quarry shines: not only can every one of its characters meet an untimely and grisly end – a blast of buckshot to the face, stabbed to death with the shard of a mirror, beheaded, frozen to death – and not only can all 8 of them survive till daybreak, but – in a new wrinkle – they can also all wind up infected by the bites of the game’s mysterious creatures. Even seemingly innocuous choices have ways of cascading throughout the story in delightfully sinister ways. Picking up that teddy bear in Chapter 1 will absolutely come back into play in a crucial way later, but I won’t say whether it’s in a good way or not. The same goes for an early choice about whether or not to bring fireworks to the bonfire party. And if a character gets bitten in Chapter 4 instead of Chapter 6, that time difference gets accounted for, resulting in conflict arising earlier in the story than it otherwise would. Sometimes inaction is, in fact, the right action. And sometimes the right decision is to pick up a chainsaw with “Groovy” etched onto the blade.

But the best thing about these games is, when they’re operating in top-form, the “wrong” choices don’t feel like punishment for the player. Instead, they add richness to the drama, as well as the horror, of the story. Take a very simple early QTE that you are asked to complete with Laura: you are running from something in the woods, but you don’t know what. If you fail to dodge a certain tree branch in the dark, Laura injures herself, receiving a cut on her forehead for the rest of the prologue. Later on, when being interrogated by a bitch-made boy-in-blue, the officer in question will raise the issue with her, asking how she got the cut. If you succeed with this QTE like a good gamer, you won’t receive this dialog at all, and instead the conversation goes in a different direction altogether. It’s honestly worth doing multiple playthroughs of this game, even trying to screw things up intentionally to see what it changes.

I also really like the storytelling in The Quarry. Early on, things seem really nuts: there’s redneck Tucker and Dale-type guys putting up hunting season signs, some sort of creature locked up in a basement, the aforementioned super creepy cop, the remnants of an old traveling circus scattered amidst the woods, and a camp leader who goes into a panic about the counselors remaining at camp past nightfall on the last day. What’s really satisfying about the story is the way that all these disparate horror tropes end up aligning by the end. These things are not red herrings, meant to creep the player out early on and then be discarded by the writers at their earliest convenience. Rather, they all have a reason for being, and the story stands up to multiple playthroughs worth of scrutiny.

Not only that, but there’s some logistical details regarding who-bit-who that end up having pretty big gameplay ramifications in the game’s final chapters. Trying to piece together the puzzle that is the timeline is very satisfying and adds an extra dimension to Supermassive’s horror formula. The biggest frustration I have with the story is an exposition dump that happens during the game’s 7th chapter. During your first playthrough, there are enough reveals and intriguing things happening that it didn’t irk me too much. However, on any subsequent playthroughs – something the game is clearly encouraging you to do – this chapter is like molasses for the story’s pacing. Spreading this information out over multiple chapters, or at least doing the exposition in a more visually interesting location could have helped mitigate the problem. But honestly, everything else is so solid that this wasn’t too big of a deal.

I wanna take a moment to touch on the cast of characters, because I had so much fun with them. There’s Laura, an independent, takes-no-bullshit type of woman that gets out in front of the horror movie plot and is ready to take action without waiting on everything to be spelled out for her. Then there’s Jacob, the jock-type unrepentant alpha-bro who seems totally down with being a fuck-boi until someone actually treats him like one. Ryan, a soft-spoken, podcast-listening loner whose loyalty to the camp leader is admirable, if misguided. Dylan, the blasé, always-has-a-joke-for-every-situation type of guy, whose flirtation with Ryan is the spiciest content in any game this year. And Kaitlin, played by Disney-alumna Brenda Song, who is “always hot, pencil-dick.”

In case I haven’t made it abundantly obvious, The Quarry is just a fun fucking time. I enjoyed several playthroughs of the game over the course of 2022 – some solo and some alongside friends in the game’s co-op mode. Unlike some of Supermassive’s other games, I felt compelled to go back and try different choices, just to uncover the different ways things could play out. More often than not, I was pleasantly surprised by some of the niche cases that were accounted for. The cast, which absolutely knocked it out of the park, are a big part of this, as I just enjoyed hanging out with them in general. That, combined with the mystery at the core of it all, made this Supermassive’s best game since Until Dawn.

7. Stray – BlueTwelve Studio

It would have been so easy for Stray to be a one-trick pony. The brilliant animation work on display with its titular cat is tremendous – possibly the best animation work in any game this year. The novelty of playing as a cat could have carried a whole game all on its own, though not one nearly as good as Stray. Contrary to its reputation, this game isn’t simply Cat Simulator 2022. Rather, it’s an excellent blend of a handful of gaming subgenres all tied up in a dystopian adventure featuring a cat and its robot partner. At its core, it’s a delightful exploration platformer, a genre that’s all too rare as of late.

Stray is remarkable in the effortless way it manages to sync up player behavior and cat behavior. The developers insightfully recognized that they could manipulate gamer instincts to have things play out like cat instincts. When you see a prompt on a door, naturally you’re gonna press it so the cat can scratch the door. Even if it does nothing, you have to interact on the off chance something happens. For you are gamer. When there’s a small railing above you that you could be walking along instead of the boring old ground? Of course you’re gonna try that. There might be some hidden path up there, after all. Just as you’re going to try these things, so too would the cat. Because, for a cat not to do such things would mean that the cat was not exhibiting cat tendencies. Cat scratches door. Cat climbs on higher thing. The world keeps turning.

In this way, Stray captures the core magic of role playing – that immersive effect that only happens when player intention and character line up perfectly. It’s a hard thing for a developer to pull off, but when you as a player feel it, it reminds you immediately why you play video games in the first place. It’s pure empathy. Immersion of character. You become bonded to the cat instantly.

Things could have stopped right there and I would have said “wow, Stray is a really special game, and you should play it”, but what made me fall in love with the game is the very fact that it wasn’t content to simply rest on its haunches. While the first couple chapters of Stray feature straightforward puzzle platformer gameplay – with you leaping from I-beams to catwalks in a dystopian, seemingly abandoned city – you eventually meet up with an intrepid drone named B-12 who teams up with you on your adventure in the hopes of recovering its memory.

At this point, with B-12 serving as a translator, you can begin to understand the dialog of other characters. You venture forward together, eventually stumbling upon a slum inhabited by numerous robots. It’s at this chapter that the structure of the game begins to shift, becoming a bonafide adventure game, complete with inventory puzzles and a wide-open hub area with lots of verticality to explore. The game doesn’t give you much in the way of direction here, providing space for the player to get lost in the back-alleys and rooftops of the area and freely interact with whichever NPCs happen to catch their attention.

By the time I wrapped up The Slums, the game’s 4th chapter, I had no idea what to expect next from Stray. And throughout my time with the game, that feeling is what kept delighting me. There’s NPC trading quests, chase sequences, a handful of combat encounters, even a late-game stealth sequence that – to my great surprise – was actually good. It doesn’t always hit the mark, but its brief moments of clunkiness are just mild blemishes on an otherwise refined experience.

There’s an astonishing amount of detail throughout the Dead City, considering it was built by a team of roughly a dozen people. There’s so much rich detail overflowing from every corner, begging to be explored and climbed on. The use of lighting alone really makes the underlying art pop in ways that And to say nothing of the wonderful musical score, which provides ambient electronics appropriate for the Dead City, and the kind of laid-back chill-vibes downtempto ambiance you’d expect to find playing inside a cat’s head for 95% of its day. It’s perhaps my favorite game soundtrack of the year, and one I would highly recommend checking out.

Stray is a hugely refreshing game – an indie project with a unique conceit and enough of a talented team (as well as budget) to immerse you in visual spendor, while simultaneously being disciplined enough to mix up its gameplay ideas early and often. It doesn’t overstay its welcome or overdramatize its story – opting instead for a less-is-more approach. It fits perfectly, as the cat has no stake in this dystopian world beyond its partnership with B-12 and a desire to reunite with fellow felines. Playing Stray was, for me, a joyful experience and one that I want to revisit soon. Maybe I’ll even attempt speedrunning it. Who knows?

6. Scorn – Ebb Software

The world of Scorn is built from flesh and stone and pain. A colossal structure reaches up out of a lifeless desert, the twisted visages of discard bodies staring blankly up at it from all sides. Mechanisms constructed from muscle and sinew control the machinery of an inhuman assembly line, processing organic lifeforms into a paste-like fuel source. Humans are grown in vats attached to the sides of cliffs, birthed backwards over sides of it, as if rappelling by umbilical cords. An infectious growth is slowly overtaking everything as it blankets the word like a cancerous kudzu.

Scorn is a gruesome atmospheric first-person biopunk game set in a world heavily inspired by the works of H.R. Giger and Zdzisław Beksiński. It really does these artists justice too, as the art direction here is perhaps some of the strongest of any game in 2022. The world of Scorn is unsettling and extremely weird, filled with out-of-body experiences and strange puzzles where you do things like move fleshy eggs around on a wall rack. It would be incoherent and completely nauseating except for the fact that the world is so fully realized that it’s impossible to look away.

Scorn is horrific, but not in ways that will make you jump or get your heart rate up to astronomical levels. Rather, its horror is that of an existential variety. It is a rare thing to find existential horror in video games, let alone horror imagery that can stay with you for days after you watch the credits roll. This typically remains the territory of cinema. Horror games put you as the player into imminent danger, immersing you in a fight-or-flight mindset that can feel much more intense than anything film can muster. Take Alien Isolation, for example, a game that puts you into a deadly cat-and-mouse game with an unkillable Xenomorph, asking you to sneak and crawl your way through its labyrinthine environments until your heart practically jumps out of your chest. But turn that game off to go to bed, and there’s nothing left gnawing at your psyche; there’s no reason to keep the lights on. The alien can’t get you. You aren’t playing the game anymore. Not so with a game like SOMA, for example, whose subject matter kept on living rent-free in my head long after I had finished playing it. Scorn, by a similar token, kept on festering in my memory like an open sore. There is imagery in the final hours of this game that is hard to forget, as much as you might want to forget it.

The animation work in Scorn goes a long way toward selling this hideous world. Each time you interact with a new mechanism, or reload one of the handful of weapons the game gives you, the level of hand-crafted detail is remarkable. Even checking the current status of your inventory makes for a chilling moment. The game is so rich with subtleties like this that I don’t want to give away. There is a moment in the final hour of the game where you will need to interact with the same nightmarish device 3 separate times. While a lesser game would have had the same animation play out 3 times – diminishing its impact with each reuse – Scorn commits to having 3 distinct, elaborately detailed, and absolutely disgusting versions of it. The animation work is used as a storytelling tool, establishing how alien this world is, but at the same time how commonplace much of it is for the protagonist.

Scorn is not for everyone. It’s ultra-violent and ultra-explicit. It’s also absolutist in its minimalism for storytelling. There are no words spoken, no text to read. You are thrust into the world with nothing to go on but some control prompts, and rest is up to you. The designers of Scorn have wisely remained tight-lipped about what exactly is going on in the game’s story. They clearly want the work to speak for itself, and that is a degree of artistic discipline you don’t often see in the games industry. Typically, you see a lot of hand wringing, and designers trying to get out in front of their games in an attempt to make sure “people get it”. If you’re the type of person, like me, that believes in the postmodern “death of the author” theory of criticism, and would rather interpret the text yourself or see what others got out of it, then Scorn is definitely your game.

5. Immortality – Sam Barlow

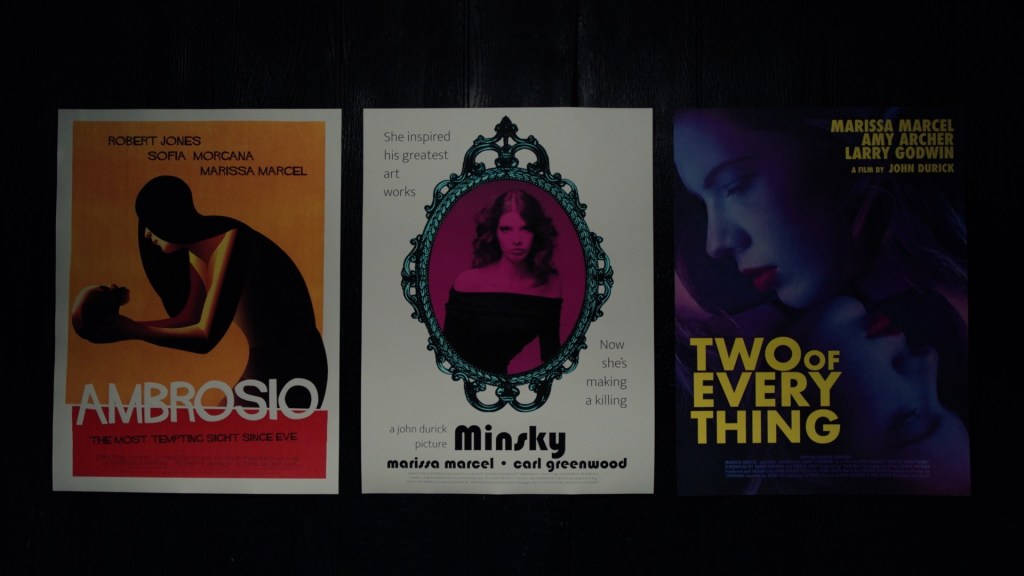

You don’t have to be a cinephile to love Immortality, the latest game from director Sam Barlow, but it sure helps. Since entering the indie scene with 2015’s Her Story, Sam Barlow has carved out a niche making FMV games that cast the player as a sort of detective, querying databases and combing through hard drives in order to piece together mystery narratives in a nonlinear manner. However, while both his debut title as well as 2019’s Telling Lies centered around police work, Immortality instead zeroes in on Hollywood mystery.

The game centers around the actress Marissa Marcel and her troubled history in the film industry. Once thought to be the next great starlet of Hollywood, Miss Marcel’s career was instead derailed by a series of unfortunate tragedies during the production of her 3 films: 1968’s Ambrosio, 1970’s Minsky, and 1999’s Two of Everything. None of these films ever saw the light of day. The game tasks the player with pouring over a catalog of salvaged film clips in an attempt to uncover what happened to Marissa Marcel.

Immortality is Sam Barlow’s most high-concept game to date. Where his previous two titles sat you in front of virtual computers via your real computer – a natural translation – Immortality attempts to emulate the usage of a Moviola film editing machine as the medium through which the player interacts with the game’s narrative. With this, players can scrub forward and backwards in time, pausing and zipping between the dozens of film clips that make up the game.

Additionally, Immortality ditches the querying concept, introduced in Her Story, for a visual facsimile born of the editing trade: match cuts. At any moment during a clip, the player can enter an image mode, clicking on a given subject – be that a particular actor’s face, the clapperboard for the current scene, even something as mundane as a coffee mug or potted plant in the background – and the game will zoom in, capture a frame of that subject, and then seamlessly transition to a similar frame from another clip in its catalog, automatically starting playback in the new clip from that point. So say you click a bottle of wine arranged on a table as part of the mise-en-scène of the 1968 production of Ambrosio, you might zoom in on it and then back out to reveal a similar bottle in the background of a party scene from 1999’s Two of Everything. That 1999 clip might be one you’ve already seen, but it also might be a totally new one altogether, and now that clip has been unlocked for you to examine further. It is through this method that you build out a catalog of clips from the measly 2 that the game starts you with, to – if you’re a completionist enough to find them all – 202 in total.

Philosophically, this is a remarkably organic method for allowing the player to dig into a particular subject of the mystery. Instead of listening for keywords in order to create a database search, you simply click the person or thing you want to examine further. Want to know who the man making eyes at Marissa is? Click his face and you’ll be instantly transported to more footage of him. This even works conceptually. Curious what Marissa’s relationship with sex was? Yes, clicking on that bare-breasted woman in one clip will match cut you with a similar clip. Just don’t expect to always like what you find.

From an execution perspective, this mechanic is a marvel to behold. The fact that it works as well as it does must have required a tremendous amount of work, both from a logistical planning standpoint (you need your shoots to have commonalities across 3 disparate films) as well as a manual labor standpoint (someone needed to tag just about everything in just about every frame). Sure, you can certainly find edge cases where the match cut struggles to connect things gracefully, but for every one of those moments, you have 9 more where it just works.

I just want to take a second to touch on the craft that went into this game from a pure filmmaking level. The way the 3 distinct eras of film are visually represented, going from Academy Ratio (1.375:1) grainy celluloid to anamorphic widescreen (2.39:1) and eventually a modern 16:9 widescreen with much more high quality film stock, not only serves the storytelling function of instantly establishing where in time we are at any given clip, but also goes a long way to selling the authenticity of this story. If you’re a film lover of any kind, be prepared to geek the fuck out at the obsessive attention to detail on display here.

From a character perspective, I love the naturalistic dialog (and likely lots of keen improv) going on here. We are given only small slices of time to get to know these characters, especially when they are not themselves acting out a scene, but what little we do get is so rich with nuance and cinéma vérité qualities that I felt like I knew who these people were by the game’s end. The performances themselves play a huge role in this, and Manon Gage (who plays Marissa) deserves massive props for carrying the emotional core of this story.

Immortality is unlike anything else I’ve ever played, barring perhaps Sam Barlow’s other works. This is my favorite game he has made, however. As interesting as his previous games were, they do have a rather cold, clinical feeling about them. Immortality has this warmth to it, this human quality that feels intimate and dreamy and eerily voyeuristic at times. Less David Fincher, more David Lynch. It makes sense too, as there are Lynchian fingerprints all over this game. Hell, even Barry Gifford (writer of Wild at Heart and screenwriter for Lost Highway) contributed to this game’s script. But I kept coming back to one movie again and again while playing Immortality, and that was Mulholland Drive. The way the game portrays this once bright-eyed actress, and her slow descent into the madness of Hollywood really harkens back to Naomi Watts’ performance in what might be Lynch’s greatest work.

Immortality is emotionally resonant and creepy and so different from anything else out there. You’re free to approach it from just about any angle or methodology. Explore the films in chronological order to the extent you can, or switch the filter to real-time if you’d like to focus on the behind-the-scenes narrative. Or bounce between all 3 timelines, taking in vignettes as you find them, witnessing the ups and downs of Marissa’s career as you try to piece things together. I even recommend playing this game with pen and paper to take notes. It’s definitely that kind of game. It’s one of the most innovative games of the year, and has me excited for whatever Sam Barlow works on next.

4. Sifu – Sloclap

To play Sifu is to experience a serious emotional roller coaster. Sifu will have you feeling like an untouchable badass one moment, only to swiftly kick you in the teeth for a single mistake the next. It punishes you for careless positioning, button mashing, even for over-reliance on finishers. If you have a crutch, Sifu will find it and make you rethink doing it again.

The game is appropriately titled then. It is the master. You are merely the student.

It’s not that the mechanics of Sifu are particularly complicated either. Hell, compared to Sloclap’s previous game, Absolver, Sifu is much more mechanically straightforward. What Sifu demands of its players, however, is mastery of its combat system. There are no shortcuts – no long combo strings to instantly wreck a boss or builds to break the game – you must simply watch your enemy, study them, learn patterns, and improve for next time.

In this way, Sifu reminds me a lot of my initial experience with Sekiro. However, contrary to Sekiro, it isn’t enough to simply skirt by a boss fight by the skin of your teeth, having not entirely learned their moveset but regardless emerging triumphant. There were numerous times that I beat a boss encounter in Sifu, only to immediately begin beating myself up for all the things I did wrong.

This is because, at the end of the day, Sifu is essentially a Rogue-like. The conceit is this: each time you are killed in Sifu, you stand back up, reborn anew, but having aged an additional year of life. Your character model changes as you burn through your precious 20s, your hair begins to gray in your 40s, and with each passing decade you gain attack power at the expense of permanently reduced health and locked-out skill tree options. Reach age 70, and it’s game over.

As such, it isn’t enough to eke out a victory against the game’s first boss. Since age is your currency to buy more retries in the late-game – when things get really challenging – you can’t afford to half-ass things. The design is uncompromising in this respect – learn your enemies not just well enough to beat them, learn them well enough to embarrass them. That’s either going to sound incredibly appealing to you, or incredibly not. For me, it was very much the former.

So that’s the gist of Sifu mechanically. But what really elevates the whole experience is the style. The art has this whole low-poly geometry with a watercolor painting aesthetic going on, and the musical score by Howie Lee has this awesome blend of traditional Chinese instrumentation – think erhu, yangqin, and bamboo flutes – and modern, heavy electronic beats that lends to the game a sense of momentum and grit. In fact, that score alone had me dying to replay various sections of the game’s five levels. I didn’t just want to achieve a better run through the level and end at a younger age, but I wanted to hear that nightclub dub track slap one more time as I crashed the dancefloor with a metallic baseball bat. You may not notice the music as much at first (who can jam out when they’re getting their ass kicked?), but as you improve at the game and start tearing your way through the game’s levels at speedrunner velocity the music really does an excellent job at making you feel like an untouchable badass.

None of this is to mention the incredible cinematic influences, all of which Sifu wears on its sleeve. Within the first 5 minutes of its first level, Sifu tries its hand at the oft-recreated hallway scene from Park Chan-wook’s Oldboy, and holy shit is it far and away the best recreation of it I’ve seen in a video game. Given the game’s rogue-like nature, you’re going to be replaying an early sequence like this a lot, so it really needed to be good, and damn did Sloclap ever deliver on it. There’s even a mid-game boss fight in the snow that very strongly evokes the Brides’ fight with O-Ren Ishii from Kill Bill, as well as that film’s most direct inspiration, Lady Snowblood. Aside from these, which are the most explicit, there’s pretty clear vibes of Gareth Evans’ The Raid: Redemption and the John Wick films present across the first and second levels respectively. There are times when film references, which are extremely common in gaming, can feel exceptionally half-assed and arguably not worth doing, but not the case in Sifu. As a fan of martial arts movies, I felt that Sifu’s reverence for the genre was clear as day.

Sifu is a game about learning from your mistakes and vying for perfection. Each boss feels designed to test the player’s ability in one of the game’s core mechanics – dodge rhythm, parrying, high and low dodges – but the designs aren’t so rigid as to rule out alternative fighting styles. The game is admittedly short, but each level is so distinct and so tightly paced that this was never an issue for me. It was so refreshing to play a rogue-like that championed hand-crafted levels and enemy encounters rather than randomized or procedural design. Sifu relies instead on its combat mechanics alone to provide the variety for replayability. That won’t be everyone’s cup of tea for sure, but for me, Sifu was an absolute joy to play – even when I was swearing up and down that I hated it.

3. Signalis – rose-engine

Singalis is a game of homages. Hell, as soon as you start it up and you’re icily greeted by the spasmodic CRT scan lines of its main menu, the distant echo of the Three Note Oddity calls out to you – the real-life broadcast of a number station believed to have been operated by Hungarian Intelligence during the Cold War. “Achtung Achtung” reverberates a faraway voice before reciting long strings of numbers in German.

It’s chilling stuff, and perfectly sets the stage for the sort of Eastern Bloc Cassette Futurism horror-show you are about to become immersed in. You play as Elster, an android (or “Replika” unit) who finds themselves on a scout shuttle that has crash-landed on a snowy planet called Leng. In your possession is a polaroid photograph of a missing woman who you’re searching for. If any of that setup sounds familiar to you, it’s likely that you are the exact type of person who Signalis was made for.

Upon making your way to the Sierpinski-23 mining facility, in which much of the game takes place, you find out that most of the Replika units there have gone rogue in some sort of infection that has been driving them all to a murderous rampage. As you venture further into Sierpinski, solving eclectic puzzles and venturing to and from item boxes to manage your tightly limited inventory, you’re likely to feel an eerie deja-vu wash over you.

Signalis is perhaps best understood as a collage of disparate sources. Just as the game’s authoritarian state of Eusan uses an amalgam of German, Chinese, and Japanese in its Soviet-esque communiqués and propaganda material, so too is the game itself a pastiche of Silent Hill’s ethereal atmosphere, Resident Evil’s strict inventory limits and twisting level design, stylistic elements from Neon Genesis Evangelion, the abstraction and dreamlike quality of David Lynch’s films, and even direct narrative references to literary works, from H.P. Lovecraft to Robert W. Chambers.

And yet, somehow, Signalis never comes across as a derivative work. Instead, it creatively operates within the ultra-specific nexus of all these distinct influences, feeling at once familiar and yet wholly its own thing. I mean, for fuck’s sake, this is a game that borrows a super specific reference to a singular save point in Silent Hill 2 – one which I recognized instantly, it was so blatant – and yet, throughout the 8 or so hours it took me to complete Signalis, I never knew what to expect next from it. Something about great artists and stealing, I suppose.

In the end, Signalis has one foot in survival horror gaming’s past and one foot in its possible future. For everything that it borrows, it offers something back to the genre. Take, for instance, the game’s usage of a radio. While the usage of radios for gameplay purposes has a clear lineage in the Silent Hill series, Signalis takes it a step further, turning it into a device for obtaining information, breaking coded messages, and even for use as a weapon against certain enemies. It’s clever stuff, and its gameplay reinforces and fleshes out the world the more you use it. Then there’s the photo module the game provides you, which serves as a sort of in-game acknowledgement that yes, solving puzzles in this game is often going to involve you taking screenshots. And while that can be achieved with a Steam screenshot or simply your smartphone camera, I appreciate that the game builds in the means to do so directly.

Signalis’ story might prove frustratingly obtuse for some, especially later in the game, as things begin breaking down and the storytelling becomes not only less linear in nature, but also less literal as well. Things which once seemed concrete and straightforward begin to start having their reality called into question. Characters begin to contradict themselves and once-reliable narrators begin coming across as decidedly less-so. The very game world begins to unravel – doors that exit one room on the left side suddenly and chaotically enter the next room on the left side again – and entire zones completely forgo having a map, as everything begins to fracture and disintegrate further into oblivion.

It would seem sloppy if it didn’t all seem so intentional. There is so much fascinating world-building, and such a wealth of lore packed into Signalis, that it becomes hard to believe it doesn’t all point to a very specific meaning. I’m still parsing my way through it all myself. In fact, I don’t even know if I love it for what it’s trying to do or hate it. But the more time I have away from it, the more I keep coming back its key moments with renewed interest.

There’s something so compelling about its approach to video game storytelling, where what you’re playing might only be an abstracted view of the primary narrative. Similar to its key inspiration – and one of my favorite games ever made – Silent Hill 2, you play what only amounts to the story’s metatext, trying to work backwards from that in order to see the text. If that sounds like bullshit to you, fair enough, but there’s this quote by David Lynch that I’d like to steal: “I don’t know why people expect art to make sense. They accept the fact that life doesn’t make sense.” With everything else that Signalis borrows, who knows? Maybe they chose to take that one to heart.

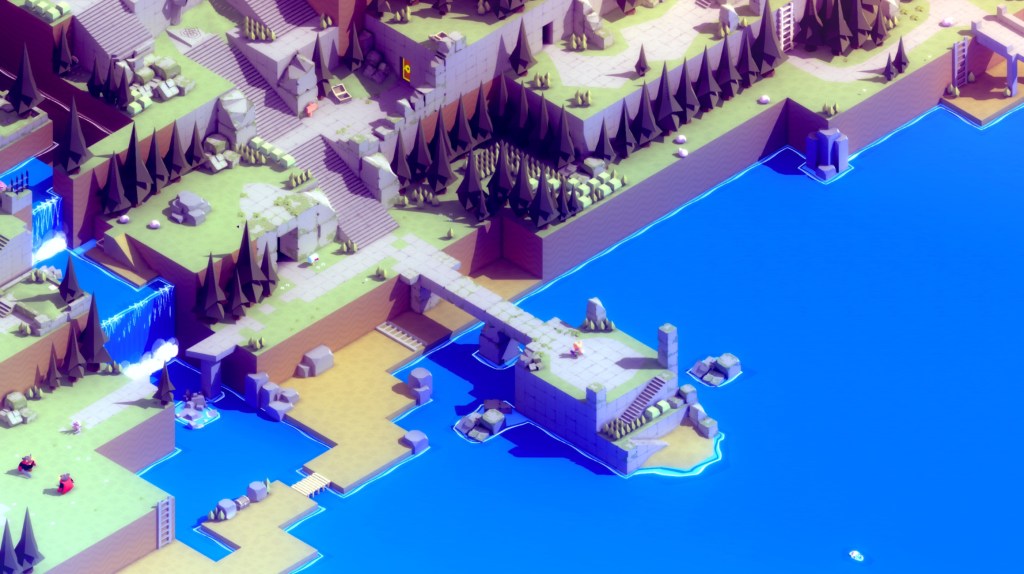

2. Tunic – Finji

Tunic is part of an imagined gaming past. It occupies a sort of shared dream-space, a Mandela effect that we all assume existed at some time during the 80s or 90s.

Tunic is so good at capturing what it felt like when you were a kid playing a new video game for the first time. Back before you knew what the limits of a game were, and when it seemed like anything was possible. At that time, every new level held the promise of some exhilarating new discovery. You would try for hours poking at every wall, just in the hopes that some invisible pathway might open up to you. You would pour over every page of a game’s paper manual, which felt like peering into some cryptic tome – you didn’t conceive of this as being written by one of the developers either, but instead by some omnipotent keeper of knowledge imparting great secrets upon you.

The fact of the matter is, as real as it might seem in your memory, that gaming past never really existed. Not really, anyway. The classic games of the NES and SNES era weren’t actually as cryptic, as dense with secrets, as Tunic is. Tunic has all the hallmarks of those classic games, complete with its own hand-drawn manual. The nostalgia runs deep within Tunic, but it actually has a lot more in common with its contemporaries than with any actual 8 or 16-bit era console game. For all the Zelda vibes, there’s just as much influence from Jonathan Blow’s The Witness or Phil Fish’s Fez at work here.

Things start out straightforward enough. You play as a young fox cub wearing a tunic, who wakes up on the shore of some new world. You arm yourself with a stick as a basic weapon, and you fight a few enemies. Eventually, you discover a large golden door, and upon touching it, witness a vision of an adult fox trapped inside some sort of crystalline prison. Clearly, your goal must be to rescue this fox somehow. Not long after this, you discover your first clue – the page from what looks like a hand drawn instruction manual. Most of the text on the page is completely illegible, written in glyphs that you can’t decipher. Mercifully, however, there are a few words of English that you can make out on the page: “Beginning your Adventure”, “Ringing the East Bell”, and “Ringing the West Bell” along with a checklist of locations. With little else to go on, you assume these are your objectives, and set out along this breadcrumb trail to ring these cardinal bells, whatever they are.

The inclusion of an in-game instruction manual is one of the primary ways that Tunic drip-feeds information to the player. Over the course of your adventure, you’ll discover additional pages of this manual, eventually piecing together the entire thing. Some are dropped directly in your path – impossible to miss – and some are deviously hidden. Some contain maps and warnings about environmental hazards, some hint at the deeper lore of the world, and some contain cryptic clues about the strangest mechanics at work in the game. The slow piecing together of this information, and the parsing of usable information buried within illustrations, paragraphs of glyph-text, and hastily scrawled margin notes is core to what makes Tunic such a unique and satisfying game.

I would be remiss not to mention Tunic’s presentational qualities as well. The game makes excellent use of isometric orthographic projection, for a view of the game world in which all vertical lines are perfectly parallel. Applied to this perspective, the game is lit entirely via dynamic lighting and global illumination, yet has been hand-tweaked enough that it is still extremely performant. It even makes use of scrolling textures in order to achieve some of its stunning visual effects work. All of this is to say, despite its small scale as an indie title, Tunic is a very technically competent game that looks absolutely gorgeous on just about any display you put it on – whether that’s something portable like a Nintendo Switch or Steam Deck, or blown up to home theater scale on an OLED panel. And – in what is becoming a bit of a running theme for 2022 – these visuals are joined with a gorgeous, ethereal synth soundtrack by Lifeformed and Janice Kwan that I’m still listening to, months after finishing the game.

Tunic is the type of ephemeral game experience that you can only really have once. To watch a stream of someone else playing the game, or to peruse the internet for hints, is to cheapen the feelings it is attempting to evoke. You’re asking the magician how they did the card trick before you’ve even seen it performed. I’ve tried to purposefully remain vague about a lot of the things in this game while writing this piece. I still worry I’ve said too much.

If you’re the type of person who needs to know exactly what you’re getting yourself into before starting a new game, then Tunic probably isn’t for you. For everyone else though, Tunic is one of the absolute best games of 2022 and an experience you won’t soon forget, I promise you.

1. Elden Ring – FromSoftware

How could it have been anything else? Elden Ring is a juggernaut, a mammoth open world game that not only feels like the culmination of every design philosophy that FromSoftware has been pursuing for the last decade plus of their history, but also sits as a kind of industry capstone – a final aspirational push toward that Holy Grail of freeform open world design that so many game developers, not to mention audiences, have been chasing after this entire console generation. From Skyrim to MGSV to Witcher 3 and Breath of the Wild, you can feel the influence of these games brought to bear alongside the eclectic and inimitable house-style of Hidetaka Miyazaki and company as you wander through the mysterious and compelling world they’ve created.

That world is The Lands Between, a rich tapestry inspired by Celtic, Norse, as well as Irish myth, and hosting what is arguably FromSoftware’s most complex and grandiose lore to date. You enter this world, in true Souls-like fashion, as a nobody – maidenless scum, lower than dirt. You are one of the Tarnished, individuals who were banished from The Lands Between by Queen Marika – the goddess and ruler of the land, vessel of the Elden Ring itself – never to return. At the start of the game, you, as one of the Tarnished, have been beckoned to return to The Lands Between following a cataclysmic event known as The Shattering, during which the Elden Ring itself has been broken. Your only clear goal is to follow the Guidance of Grace between various Sites of Grace – this game’s holy equivalent to Dark Souls’ slovenly bonfire – to seek out and kill the realm’s demigods, children of Queen Marika and King Radagon, usurping them all and taking over as the Elden Lord.

At least, I hope I got all that right. Little of this is explicitly stated to the player, and instead much of the story must be inferred from interactions with other characters, the descriptions of items, or simply the visual storytelling at work in the game’s environments and enemy design. Other characters will even lie to you at times, both by ignorance and in attempts to deceive you, so you have to be ready to course-correct your understanding of the world as needed.

Similarly, the game does not directly tell you where to go outside vague Guidance of Grace suggestions and environmental hints. If you see a large castle towering above the rest of the land, it is likely that will be a place you should go, but taking a direct path might also be an inadvisable method of progression.

The game establishes this key concept very early on in 2 encounters. First, it places a large mini-boss – the golden armor-clad, mount-riding Tree Sentinel – directly in your path from the moment you find your first Site of Grace checkpoint. For all but the most sweaty Souls-enjoyers out there, attempting to fight this boss will result in an ass-beating that can only be described as humbling. You might get brave, trying this fight once or twice, but you will almost certainly fail, eventually finding a way to run or sneak by him and his asshole steed on your way to the Church of Elleh. From here, things will calm down a bit to a more approachable difficulty. That is, unless you decide to follow the path all the way up Stormhill and into Stormveil Castle’s entrance tunnel. If you do this, without any curiosity to explore elsewhere first, you will be met with one of Elden Ring’s most infamous encounters – that of Margit, The Fell Omen. As the Omen title suggests, this boss is a taste of what Elden Ring has in store for you. In my first playthrough, I died to this boss – a lot. Look online and you will find entire montages of streamers dying to this boss – a lot.

Within this single boss encounter, we can observe so much about Elden Ring’s design. His function in the game is to quite literally serve as a gatekeeper, beating down overzealous players until they understandably give up, leaving the castle to explore elsewhere. In this way, Elden Ring teaches its players – without resorting to tooltips or patronizing warning messages – that difficulty spikes will be the norm, and that you do not have to fight anything that you don’t feel prepared for. If you go explore the rest of Limgrave – the region of the map surrounding Stormveil – you will find that nothing there is quite as challenging as Margit. You are free to explore, level yourself up, become more comfortable with the timing of dodges, parries, and the like, before eventually returning to give Margit his just deserts.

In this way, Elden Ring feels like an improvement to Breath of the Wild’s “go anywhere” design approach. With rare exception, you are never gated from going somewhere by anything save the difficulty of getting there before you are the proper level. But if you can surmount those obstacles with raw skill, nothing will stop you. This remains true deep into the game, and is one of the most compelling aspects of it. You can get lost for hours heading down a challenging but clearable path that you perhaps are under-leveled for, and then be rewarded for your efforts in reaching a new area early. The difference here vs Breath of the Wild is that the game is challenging enough that it feels like there are meaningful reasons to unturn every stone in the game. You never know when the random cave you’ve stumbled upon might contain something absolutely perfect for your build – or better yet, something so good that you want to adapt your entire build around it once you discover it. In this way, Elden Ring is always operating on a push-pull design approach to exploration. Sometimes the game is all carrot, sometimes it’s all stick.

What’s so impressive about the translation of the Souls formula to an open world format is that I never found myself missing the tight, hand-tuned level design of previous entries while exploring Elden Ring. The game’s cheekily named Legacy Dungeons, as it calls them, are giant, instanced-off areas that feature some of From’s best, most structurally complex level design ever. Just using Stormveil Castle as an example – the game’s logical “first” Legacy Dungeon – it opens up with a central junction point: approach via the heavily guarded main gate or covertly along the cliffside through a hole in the castle wall. Both of these paths eventually reconnect, and you’re likely to want to carve your own route through both areas to find everything that they each hide. Not only that, but once inside the castle, there are secret paths to discover along its rooftops, breadcrumb trails leading to sidequests back out in the open world, and even entire boss fights hidden in difficult-to-find sections of its lower-levels. It’s incredible stuff, and I found myself finding new things every single time I played through Stormveil with a friend in co-op. It is some of the best level design of the entire year, and that’s just dungeon #1 for Elden Ring. An embarrassment of riches.

None of this is to say that Elden Ring isn’t flexing when it comes to the open world design either. Quite the contrary, Elden Ring is just as exciting when wandering between the smaller locations scattered throughout its map. Each of the game’s smaller areas, be them caves or catacombs or ruins, have a handcrafted quality to them, even employing unique gimmicks that keep things feeling fresh for far longer than I’ve ever felt in any open world game. Sure, it gets old eventually, and you really start to feel where FromSoft had to start recycling assets and enemy designs as the scope of the game eventually reached the team’s limits, but that feeling of wide-eyed discovery is maintained for dozens of hours. You’d be hard pressed to find me another game that can keep that feeling of awe going for longer than Elden Ring manages. I’m not sure one exists.

The interconnectivity of the world deserves a mention as well, as it is perhaps the most mind-melting aspect of the game. What would normally be small dungeon instances in any other game can suddenly link up with wide expanses – paths that daisy-chain to even more paths – honeycombing off into so many possible directions. Without spoiling too much, let’s just say that one of Skyrim’s coolest moments, the discovery of the Blackreach caverns far below its icy landscape, is pretty much par for the course in Elden Ring. Not only that, but pay really close attention to NPC dialog and you might even find obscure sequence skips actually built into the game – the kind of thing that might look like a wrong warp bug in any other game, but amidst the insanity that is Elden Ring, feels right at home.

Much has been said about how Elden Ring doesn’t handhold its players, how it respects its audience enough to resist littering its map with a scatterplot of markers and pins and waypoints. A lot of people pick up on this as the developer treating its player-base like adults – they are not wrong. This is all well and true. What really struck me about the way Elden Ring was designed however, is the massive degree of confidence it must have taken to be willing to hide some of its most extravagant areas, some of its most compelling secrets, deep behind layers and layers of obscurity. There are many, many players who may not find major sections of Elden Ring, and I love that about it. Not because I have some desire to make Elden Ring exclusionary to more casual players, but because designing the game this way – when you can find a single invisible wall or a small hole in the ground and uncover massive sections of the game – ignites your imagination and offers huge rewards for your time spent methodically upturning every stone.

Let’s return to that Margit fight for one final point about Elden Ring’s design – the combat. This is where things might be a bit more divisive than the unmitigated slam dunk that was the world and level design. FromSoftware has chosen to speed things up considerably from the Souls series. Bosses move a lot more like they did in Sekiro – they are lightning fast, they will read your movements to punish everything from a reliance on spells to the sloppy timing of your heals, and their attack timings are mathematically dialed-in to punish any instance of panic-rolling. Some are so insidious with this that they will actually feint you with the kind of mind games that were previously not seen outside of PvP fights. You’ll find Margit doing all of these things in his crash-course introduction to the game.

All this, combined with the propensity of bosses to throw out AoE attacks, ultra-deadly status effects, or gank the player with multiple enemies at once, makes for a game that feels balanced around co-op or the new Ash Summon system first, pure solo-play second. Sometimes things feel overbearingly brutal, other times laughably easy. As you play more and more you can feel Elden Ring struggle with this, as the ridiculous amount of combat and exploration options you have creates friction against its difficulty balance. As a fan of FromSoftware’s challenging gameplay, I struggled personally to make peace with this, stubbornly wanting to fight every boss I could without help from humans or AI summons. Doing so can prove to be an exercise in frustration. Your mileage may vary with this, as you may find that the tradeoff between freedom of choice and combat balance was worth it. Speaking for myself, I found this to be the area where Elden Ring’s ambition cost it the most.

Elden Ring is that magical type of game that reminds you why you play video games to begin with. It reminds you that design conventions are merely suggestions, and games, even ones as large in scope and budget as Elden Ring, don’t have to follow them if they have more interesting ideas to explore. Somehow, in spite of all their many of successes, FromSoftware still seems to be operating at a level of creativity and passion that we’ve rarely seen maintained at the highest levels of the games industry – all too often, we’ve seen these artistic qualities vampirically sucked dry by the likes of short-term investors and risk-averse capitalists. Elden Ring then, is a marvel not just of game design, challenge, and storytelling, but also of its ability to withstand the pressures of the industry and get made, without meddling or interference, in the first place. The fact that it became the phenomenon it did in 2022, the fact that sales were as sky-high as they were, might be a positive example to the industry that betting on unique creatives is a worthwhile endeavor and the path forward to lasting success. Or maybe it’ll just be written off as unreproducible lightning-in-a-bottle, and we’ll be right back to square one, with game companies seeking easy shortcuts to financial gains? Maybe some enterprising young MBA-type will figure out a way to insert NFTs into a future FromSoft title, and we can all own our own personal rune from the Elden Ring? Who knows…