2020 really was a more innocent time. For last year’s list, I had this whole, cute little intro that I wrote. I still had a sense of humor about how bad everything was getting.

2021, the year, has taken a lot of that out of me.

So forget the intro this year. Why reflect on the year as a whole, when we all know it was a pretty bad one? Let’s talk about the games that came out this year, because some of those are actually pretty good.

Real quick, before I get into it –

Quick obligatory notes:

- This is a ranked Top 10 list with 3 honorable mentions (unranked).

- Each game features a link to one of my favorite pieces of music from its soundtrack. Feel free to listen as you read.

- I consider the release timing of Early Access games based on when they exit Early Access, or enter V1.0.

- Remakes (which are becoming even more common these days) can be on my lists, but only if they are substantial enough in that the game is something fundamentally different. Examples of games I counted in 2019 were Pathologic 2 or Resident Evil 2. In 2020, I didn’t consider a game like Demon’s Souls (even though I loved it) because it is mostly a visual overhaul to the 2009 original game. Hopefully that distinction makes sense and isn’t just arbitrary to you.

- I’m never able to get to all the games I’d like to by the end of the year. There are always ones that slip through the cracks. I typically like to list up front the games that I had the most interest in that I admittedly didn’t have time to get to. This year, my pile of shame is as follows:

Pile of Shame:

Eastward

Wildermyth

Bravely Default 2

Alien: Fireteam Elite

Persona 5 Strikers

Okay, with that out of the way, on to the list…

Honorable Mentions:

The Dark Pictures Anthology: House of Ashes – Supermassive Games

The brilliance of Until Dawn – Supermassive Games’ 2015 title for PS4 – was in the ways it toyed with genre conventions. By the time you got to the game’s fifth chapter, it had been riffing on elements of a teen slasher, a creature feature, a ghost story, a torture porn, and a serial killer mystery. There were references and tropes galore. But the big reveal later in the game was that only one of those was the “real” genre – or rather, only one of those perceived threats was the real one all along. It was a fun way to keep the player guessing, participating in the mystery, and in the dark about what could and couldn’t actually kill their playable characters.

Not to mention, unlike games like Heavy Rain, it never felt like you were getting “less” of the full story when one of your characters ended up biting the big one. It didn’t feel wrong when Emily died; it felt perfectly canonical to me. Because in horror movies, people die, and the story moves forward. As such, it made perfect sense to make a Quantic Dream-esque game set in the deepest of horror camp.

Supermassive’s big project since then has been an anthology series of games based around similar “Butterfly Effect”, decisions-with-far-reaching-consequences type gameplay. The Dark Pictures Anthology – as it’s called – has so far been an interesting project, but not one I would say has risen to the high bar that Until Dawn set for the studio. Each of the prior two installments – Man of Medan and Little Hope – have had their own unique problems, but they share a crucial one: the big twists in each have had a strange aversion to the supernatural or fictitious. Essentially, the big scary threat in both was simply all in the characters’ heads. This wasn’t necessarily a terrible idea, but it lacked the sort of punch that Until Dawn’s out-of-left-field creature reveal had.

After Little Hope, I began to worry that this was going to become the story formula for all future Dark Pictures games – as in, “don’t worry y’all, monsters aren’t actually real”. Well imagine my excitement then when House of Ashes gave me not only some honest-to-goodness cave-dwelling freakshows, but also a late-game genre changeup that I never saw coming.

House of Ashes follows a team of U.S. Marines during the invasion of Iraq in 2003, as they are hunting for weapons of mass destruction hidden in an Iraqi village. Unsurprisingly, they don’t find any (wow, just like real life!), and instead are met with a firefight with the Iraqi Army. The fighting gets a bit out of control, and the ground gives way around our main characters, who fall into an old cave system below the village. As they look for a way out, they discover they have actually stumbled onto a 4,000-year-old Akkadian ruin, as well as something a bit more sinister. Queue the horror trailer stinger.

House of Ashes wastes little time. The introduction to the characters is fast and quickly filled with drama – one marine is sleeping with the not-quite-so-ex-wife of another member of the group – and, once inside the cave system, it doesn’t take but a few minutes before the whole thing devolves into an absolute madhouse. The pacing of the game is quite good, leaving little downtime for things to get boring.

In addition, one of the best things Until Dawn did, that House of Ashes practically triples down on, is the length of time between player decisions and the consequences. Rather than the simplistic cause and effect of some other games, where the decision is immediately followed by the outcome, House of Ashes has you making seemingly immaterial decisions early on that come back into play in big ways later on. To me, that’s a much more interesting way to handle that type of decision-tree gameplay. It heightens the suspense while also making the replayability richer, since things are being set up and paid off across the whole storyline instead of just isolated moments.

Certainly, the best element of the Dark Pictures games has been the introduction of a co-op mode. Essentially, you and a friend will alternate control of different characters based on what the scene requires. So, in a scene where Eric and Rachel, the estranged husband and wife, explore a large antechamber, player 1 might control Rachel while player 2 controls Eric. Straightforward stuff. Where it gets interesting, however, is when characters start getting separated. At that point, you’ll have player 1 experiencing an entirely separate chapter with Rachel than what player 2 is experiencing with Eric and the other marines. And this plays out simultaneously. So, when your friend starts reacting to a jump scare in your Discord VC, you will have no idea what they’re seeing on their end. Conversely, you might be learning valuable information about the cave-dwelling creatures that you’ll want to verbally relay to your friend, so they aren’t operating on incomplete information. It’s very meta in that way, in that it makes you and your friend feel like two active participants in the horror film that’s playing out. It’s absolutely my recommended way to experience House of Ashes, as it adds a whole other layer of tension that wouldn’t be there otherwise.

I really don’t want to spoil the late-game stuff in House of Ashes here. Let’s just say that while the mid-game draws clear influence from 2005’s masterpiece horror film The Descent, the finale of the game goes for something just as clear, but a very different inspiration. The reveal had both myself and my friend I was playing co-op with asking each other where the hell this whole thing was going. It was one of my favorite gaming moments of 2021, one that reminded me of the first time I played Until Dawn and had both me and my friend down bad for the next Dark Pictures game. With House of Ashes, The Dark Pictures project has gone from kinda-mid to me to kinda-fire. October 2022 can’t come soon enough.

It Takes Two – Hazelight Studios

It Takes Two is the rare co-op game that is actually designed around being a cooperative experience. A lot of games just look at co-op as a mode – a nice way to enjoy single player content with a friend. Or to be a bit more generous, they might be balanced around having 2-4 players working together, but that just makes the shooting or whatever easier – nothing some bots and a single competent player couldn’t handle. It Takes Two, by contrast, is designed entirely around the idea of co-op, so much so that the entire game plays out in splitscreen, whether you’re on the same couch as your partner, or half the world away. Many puzzles require constant communication, patience, and a sense of empathy for what unique thing your partner is having to do. When it works it really works, and the gameplay serves as a bonding experience in its own kind of way.

When it comes to levels, It Takes Two has a creative energy to rival that of Super Mario Galaxy. Nearly every twenty minutes, time and time again, the game reinvents itself, throwing some totally new gameplay element at you and your partner. And just before things begin to drag or get boring, it’s onto some new high-concept idea, or some new miniaturized location – oftentimes both.

Early on, when Cody and May are shrunken down and navigating their own backyard shed, May gets a hammer and Cody gets a nail, and the Cody player will need to throw nails into walls, creating places for the May player to swing on. In another level, each player gets a magnet of a different polarity, and you’ll need to work together in a variety of push/pull fashions to get past obstacles. Then there’s an entire space level where one player has antigravity boots and the other can grow to massive size or shrink down to microscopic scale. The game is smart about things like that: typically it’s giving each player their own gameplay tool as opposed to having both players doing the same thing. It’s a good way to keep players reliant on one another, rather than the more skilled player simply progressing faster and waiting on their partner to play catch-up.

Unfortunately, while the individual game mechanics never stick around long enough to overstay their welcome, the same can’t really be said of Cody and May themselves. The game runs about 12 hours at a good pace – or 15 if you and your partner take things slow – and their schtick really begins to wear on your patience after that much time.

At the very beginning of It Takes Two, it’s established that Cody and May are planning on getting divorced. They waste little time in informing their young daughter, Rose, of the situation, and her sadness and confusion at this news creates the inciting action for the plot. It’s a pretty rare thing for a video game to depict the concept of divorce at all, and to combine that with a co-op game, where new partners will often bicker with one another as they each acclimatize to each other’s way of playing, is a pretty inspired choice. Early on, the character dialog between May and Cody often mirrored what my co-op partner and I were saying to each other in Discord. In this way, the idea itself is actually quite ingenious.

Where it begins to collapse, however, is in the mid to late game, when the game begins losing narrative focus. It can’t seem to decide whether it wants to be a getting back to together story or not, and because of this, the characters arbitrarily bounce back and forth between attempts at rekindling their feelings for each other and resuming their bickering ways. Normally, messy character arcs and clumsy storytelling are the kind of thing that are easy to forgive in games, but here, there isn’t a lot of momentum to pull you through the game otherwise. Since the game riffs on its gameplay elements so frequently, never letting one idea incubate for too long, it becomes incumbent on the story to keep you and your partner coming back for session after session until you beat the game. Sadly, once you start hunting for page fragments, the game just loses any and all urgency.

That said, It Takes Two is still a really special game, and one that I’m exceedingly glad got made. Josef Fares, the director of the game, has been working on really cool stuff for a while now – from Brothers: A Tale of Two Sons to A Way Out – and it’s great to see him and his team finally getting some major recognition for their work. It Takes Two has some of the most memorable moments I had with a game all year. That sequence with the Cutie the elephant alone is one of the most shocking things I’ve seen in a game in quite a while, and to witness that along with a friend is definitely an experience, to say the least. If you have a close friend to play It Takes Two with – especially one who is less familiar with games – it really will be an experience that neither of you will soon forget.

Hitman 3 – IO Interactive

I just can’t quit you, Hitman. Though the high isn’t quite as potent the third time around, there’s no denying that the new iteration of Agent 47’s emetic poison-laced misadventures are some of most satisfying, clever, and out-and-out hilarious games of the last half-decade. Hitman 3 represents the culmination of a lot of ideas the developers at IO Interactive have been kicking around ever since that first Paris fashion show level all the way back when this series was supposed to be episodic (yeah, I forgot about that too). There’s a decent bit more experimentation with the formula this time around, and while not every new idea succeeds, this new collection of Hitman levels are by and large some of the most dense and intricate murder sandboxes the series has ever produced.

Let’s talk about levels. This time around, Agent 47’s digital tourism takes him to the opulent penthouse floors of a massive skyscraper in Dubai, a foggy English manor complete with Scooby-Doo-style secret rooms behind bookcases, an eccentric Berlin nightclub built out of der fonkybeatz and the concrete of a decommissioned nuclear plant, the rain drenched neon alleyways of Chongqing, and a sun washed wine estate in Argentina. The artistry for these locales is excellent, and just walking around and admiring the detail of them is quite enjoyable. From a design standpoint, the levels are a bit more focused overall than the labyrinthine maps of Hitman 2, although I admit to still having a bit of a soft spot for behemoths like the Santa Fortuna and Mumbai levels from that game. Instead of sprawl, here the levels are all about tightly packed density – seemingly no space is wasted in Hitman 3’s worlds of assassination.

Of the new ideas they experiment with, perhaps the one that works best is the Berlin nightclub level, in which Agent 47 is being hunted by 10 other assassins. There are no glowing red targets when things kick off – instead, you must be observant and search around for the disguised agents. The level, appropriately titled Apex Predator, is the only time in the entire series where you are given no Mission Stories, and are instead set loose on a very freeform manhunt. My first time playing through this mission, I wasn’t really a fan of this design, but I think this is the mission that benefits the most from subsequent playthroughs, and over time it became one of my personal favorites in the series.

Not to mention the level set in Chongqing, China, which is my personal favorite of the entire game. It’s the game’s most complex map, with layers and layers of verticality spanning high-rise apartments and hidden underground labs. And the whole level just has some extremely moody noir atmosphere to top it all off. It’s a level that I enjoyed every minute of being in.

It doesn’t all work, however. The final level is a very linear, very boring train map with no Mission Stories – something that worked for the Berlin mission’s unique structure but here just feels like a cop-out. I understand that the idea was to have a final mission to focus on the ending of the story, but the result just doesn’t work and it is by far the weakest level in the entire trilogy. It’s a shame the finale puts such a bad taste in your mouth, as the other five levels are so immaculately designed, but c’est la vie.

With Hitman 3 in the tank, I think it’s time for IO Interactive to let Agent 47 take a well-deserved sabbatical. While this game is a brilliant capstone to a trilogy of bangers, I think now would be the perfect opportunity for the developer to try something new. A team this talented almost certainly has a lot more ideas up its sleeve, and I want to see what else it’s capable of. Let our favorite barcoded agent take a bow. The encore can wait. After all, it’s always better to leave the people wanting more, wouldn’t you say, 47?

Top 10:

10. Humankind – Amplitude Studios

2021 featured two different doppelgänger games – the less generous among you might call them clones. Those were Back 4 Blood and Humankind. The first was kind of unique in that it was technically created by the same people who came up with the original idea for Left 4 Dead. Unfortunately, without the help of the team at Valve Software, Back 4 Blood was merely a hollow shell of disappointment when compared to its forefather. Humankind however, an unapologetic homage to Sid Meier’s Civilization series, turned out to be an unexpected gem of a strategy game, and not at all a disappointment to its dad.

What sets Humankind apart from Civilization is the ways in which it emphasizes player flexibility throughout a given game. For starters, the biggest and most prominent change to the Civ formula is that Humankind allows you to select a different empire of history – complete with all the specializations and unique units that entails – at the start of every era. So rather than selecting an agrarian society out of the gate and then being locked into food production as your sole focus, you can actually play a lot more responsive to what’s happening at a given moment in the match.

Say you start out agrarian and that helps you build up a very populous empire in the early game, but later you realize that other players are outstripping you technologically. At that point you might choose a science-focused culture in order to shore up that weakness. Or, if you’re really paying attention, you might see an opportunity for synergizing with a tech focused culture like the Greeks, who get bonus science for every extra person working as a researcher for your city. With a high population driven by an early game agrarian culture like the Harappans, you’re now setup not just to play catchup on science, but possibly even usurp those that min-maxed in the early game.

In this way, Humankind encourages its players to experiment early and often, including well into the late game. That’s incredibly refreshing, as someone who’s played plenty of min-maxed “tall” empires in Civs 5 and 6. Another way it eschews convention is by doing away with Civ’s victory conditions altogether and replacing them with a point-based Fame system. While this seemed a bit tacky to me at first – are our empires really being assessed by who got the most gold stars from teacher? – I eventually came around to preferring this method over strict scientific/cultural/diplomatic/militaristic win conditions. Again, because the points are awarded based on achievement throughout the game, there is more incentive to play a balanced empire – or even a hybrid empire – than to simply Zerg rush toward some pure, technologically utopian city on a hill.

Humankind also has a strong emphasis on threading your decisions together into a coherent “narrative” across a single game, with you as leader and your empire’s people in constant dialogue with one another. The ideology system tracks various decisions you make throughout the game, accounting for your attitudes on individualism vs collectivism or liberty vs authority, and these political tendencies will open new opportunities for Civics while also locking you out of others. Then there’s how the game handles war: declare a conflict on an empire you have grievance with and your people will support your decision as a leader, but betray a close ally with a surprise attack or begin sacking the cities of an empire who shares your religion, and your people’s support for your war will tank, leading to instability and rebellion in your cities. It’s a great dynamic, and one that provides a bit of a monkey wrench to the old “my ally is about to win the game, so it’s time to nuke him” strat.

The great irony of Humankind is that despite being a Civilization lookalike – a somewhat uninspired idea on its surface – it brings so many fresh ideas to the mix that it reinvigorated my love for the genre as a whole. It was a pretty ballsy move to create a direct competitor to one of the most long running and renowned franchises in gaming. Even ballsier to question dogma and retool what might be considered sacrosanct. And to do all of this and actually stick the landing? Power move.

Your turn, Sid.

9. Metroid Dread – MercurySteam, Nintendo EPD

A lot has changed in the Metroidvania genre since Samus’ last 2D outing – 2002’s Metroid Fusion. Since then, we’ve seen the likes of everything from Shadow Complex, Axiom Verge, Guacamelee, Hollow Knight, Bloodstained: Ritual of the Night, to both Ori games, as well as many others, arrive on the scene, each with fresh ideas and unique takes on how to push the genre forward. Now, just shy of two long decades later, Nintendo has bestowed upon we unwashed and unworthy a brand new entry of its own, lest the Zoomers begin to think that Samus is just a character from Smash Brothers.

The thing is, I’m not so sure Dread has a whole lot new to say. It’s not some ground-breaking sequel that rewrites the playbook for what a Metroidvania can be, nor does it seem particularly interested in doing so. Instead, Dread is simply a very good Metroid game. And that’s okay, because those are still a particularly rare commodity these days.

The big, back-of-the-box feature of Dread, the invulnerable E.M.M.I. hunter-robots, certainly deliver on the game’s namesake – they are fast, relentless, and oh-so-very deadly. As soon as one gets ahold of Samus, you only have two chances at escaping an insta-kill, and the timing window is random and borderline frame-perfect for each. Given the difficulty of doing this reliably, confrontation with an E.M.M.I. at no point feels like a viable strategy for getting past one. Instead, it’s much better to rely on the game’s stealth mechanics, and, failing that, simply haul ass to the nearest exit. The idea of stealth in a Metroid game doesn’t sound particularly compelling, but in practice it actually works quite well. There were a lot of times where I had an E.M.M.I. scanning the room mere inches from my cloaked Samus’ hiding spot. It’s hard not to hold your breath in these moments.

As attention-grabbing a feature as the E.M.M.I. mechanic is though, it largely doesn’t change much from encounter to encounter. Funnily enough, it isn’t the game’s unkillable enemies that are the main highlight; instead, it’s the ones that Samus can unload a volley of Super Missiles on. The combat is what stole the show for me in Dread.

Combat is sped up a bit from Metroids prior, and the addition of slide, warp dash, and parry abilities allow for significantly more close-range options. These abilities also go a long way into allowing the player to control the pace of combat, rather than the enemies’ attacks dictating the flow. This is most clearly demonstrated during Dread’s fantastic boss encounters, where the end of a long attack pattern might be followed with an attack that Samus can parry. With the right timing, Samus will deflect the attack, mount the boss, and trigger a grappling sequence during which you still have full control of her arm cannon. Watching Samus standing inside the maw of a boss, prying its jaw open with one arm while unloading Super Missiles into its throat is definitely one of the coolest moments I had with a game all year. It is extremely fucking satisfying.

Related to that, it’s worth shouting out the animation work in this game, because it really goes a long way in selling Samus as a character. Her depiction in Dread is probably my favorite in the history of the series. Through body language alone, you can tell that Samus has been through quite a lot, and has little mercy or patience for creatures that stand in her way. For her, this all seems routine at this point, and there’s something about the confident way she carries herself that had me thinking, holy shit Samus is a badass.

As excellent as the game is, I have two main bones to pick with Metroid Dread that keep it from placing higher on this list for me. The first is the controls, and how needlessly complicated they are. It’s not that the controls are bad per se (you can make Samus do exactly what you want, and movement is very responsive), rather it’s the degree to which you need to make claw hands in order to reach everywhere you need on the controller. You can certainly master Dread’s controls, but it took me until the final couple hours to truly feel comfortable with them.

For every action, you have to be very explicit about what you want to do by holding various toggle buttons. I’m sure this method of input will make it very popular in the speedrunning/challenge run community, since the game makes zero assumptions about what you want to do and allows for maximum speed of on-the-fly changeups. However, for a casual player trying to enjoy the game, it makes the lengthy patterns of boss and mini-boss fights pretty exhausting to get through. It’s been years since I’ve had a game cramp my hands quite as bad as this one, and frankly I don’t think the tradeoff is worth it at all. And don’t even get me started on how you store a Shinespark to use later in this game…

The other issue I have with Dread is its world design and art direction. While the levels are cleverly laid out and satisfying to navigate, the visuals don’t do the game a whole lot of favors in making me want to explore the world. The sterile corridors of the E.M.M.I. zones and the industrial look of a lot of the early game just don’t do a lot for me. Compared to modern Metroidvania games, this is where the game feels the least inspired.

Metroid Dread might not be the most ambitious Metroid game, but it’s certainly a welcome return for one of my favorite game series of all time. The level design is excellent, and it has a lot of really clever ways of shepherding you down the intended path without you realizing it’s doing so. It has some of the most fun boss fights the series has ever had, without relying too much on the old favorites. And the new E.M.M.I. cat-and-mouse game does enough to mix things up without hijacking the traditional Metroid formula wholesale. It’s a great entry in a criminally underutilized series, and hopefully its success will mean that we won’t have to wait another two decades for Nintendo to bestow us with another.

8. Death’s Door – Acid Nerve

When it comes to top-down Zelda-likes, I usually find that most of them come up short. Of the laundry list of things that make Zelda games so special, most imitators only seem able to fulfill a handful. Few games manage to hit all of the high notes.

Not so with Death’s Door, which effortlessly ticks all the boxes you could want from a Zelda-like game. It’s got heaps of secrets to uncover and ways of rewarding your curiosity. It’s got cleverly designed dungeons filled with puzzles and combat, topped off with a memorable roster of great boss fights. It’s got a colorful cast of weirdos to meet, an often-overlooked element of the best Zelda adventures. And yeah, it’s even got the music covered; the soundtrack has a seriously broad scope, with memorable character themes and instrumentation choices (just listen to how different “Avarice”, “The Stranded Sailor”, and “King of the Swamp” are from one another).

Death’s Door is at its best when the driving momentum of its soundtrack and the step-dodge-attack beats of its combat are working in tandem. Take the Inner Furnace level from early in the game, where piston-like platforms rise and fall in time with the music. As you work your way through the level’s combat gauntlet, the music and pistons harmonizing the whole time, the rhythm subconsciously sets the pace of the fights that play out. Just a few rooms in, I found myself dodging and attacking on-beat, as if suddenly this were a Crypt of the NecroDancer game.

All the while, the tone of Death’s Door is this delicate balance of melancholy, grandiosity, and tongue-in-cheek humor. For a lot of the game, the world you traverse feels sparsely populated – nearly devoid of life, save for a handful of souls. And your job, as a Reaper Crow working for the Reaping Commission Headquarters, is to extract some of those last remaining souls. The whole game is done from a stylized isometric perspective – giving it some qualities of tilt-shift photography – which serves the game well both from a thematic and aesthetic perspective. Of course, the game looks gorgeous, but there’s also this omniscient quality to the camera – overlooking all of the action like miniatures on a film set – that feels like watching the whole thing through the eyes of a god – watching everything in silent judgement or as a detached comedy, depending on your view.

And let’s be clear: Death’s Door is a very funny game. There were numerous points where the game had me laughing out loud to myself while playing – a rarity for me. Even the gags with the way the game handles text really got to me. Little gags, like seeing the word ceramic written in wavy font as if it were some particularly vile adjective really got me chuckling to myself. The characters of Pothead and Jefferson were particular highlights, and I enjoyed pretty much every moment they were onscreen.

Death’s Door was a wonderful surprise in a somewhat sparse and disappointing year. It’s a good thing, because in a more crowded release calendar I might have let a gem like this fly under my radar. And I’m so glad I didn’t miss this one, because it’s one of the most well-crafted and fun Zelda-like games I’ve played in years. It’s so well polished and confident in what it wants to be that when you play it, you just feel like you can let go and let the designers take you for an adventure. That’s the kind of praise typically reserved for Nintendo games. So, I think that means that, yeah, they really nailed every aspect of the Zelda homage.

7. Monster Hunter Rise – Capcom

The Monster Hunter series is perhaps the greatest advocate for iterative game design in the industry. Typically, this approach gets a bad rap, and not without good reason. Look no further than Ubisoft’s catalog, and the way they have cynically deployed the same formula again and again with only modest aesthetic changes. That said, there’s something about the way that Monster Hunter chooses to continuously refine and augment its core gameplay loop that really works for it. Rise, coming hot off the heels of the extremely popular Monster Hunter: World, has some very clever new ideas that had me falling in love with the series all over again.

Ask any Monster Hunter player what the least interesting part of the game is, and you’ll probably get several variations on a theme vis-à-vis the movement. Chasing down and hunting monsters is a blast, but actually walking your character around from fight to fight? That gets old pretty quick. In Monster Hunter: World, that was something you just sort of dealt with. Rise attempts to tackle this problem in a couple ways.

The first is the introduction of Palamutes – canine cousins of the series’ familiar feline friends Palicoes – a new combat buddy type that assist you in your monster-slaying routine. However, what sets these doggos apart from the series staple buddies are that they are mountable. At any time, holding the interact button calls over your Palamute to your hunter like a faithful steed. They are significantly faster than your hunter’s sprint speed, with unlimited stamina, and even the ability to drift around corners, Mario Kart-style. It’s a very welcome addition.

When the need arises to travel a little more vertically, that’s when the new Wirebug mechanic comes into play. These are firefly-like insects that you can deploy along a wire, quickly zipping your hunter in their direction. Effectively, it’s a grapple hook, but it doesn’t need anything to attach to. Combine this with the ability for your hunter to wall run, and nearly any cliff-face becomes traversable in moments – eat your heart out, Breath of the Wild.

Between the Palamutes and the Wirebugs, movement has gone from a chore to a joy. And not only that, but because Monster Hunter Rise wastes no part of the Anjanath, both these new mechanics factor into the combat as well. You can, of course, use your weapon to attack from atop your Palamute, but also, a well-timed leap off its back can set you up for a devastating aerial plunge attack onto a monster’s hard-to-reach weak point. Then there’s the Wirebugs, which have all sorts of useful combat techniques based on the weapon you pair them with. My hunter’s weapon class of choice was the long sword, and so the Wirebug allowed me to set up a powerful counter window on a monster. Or my personal favorite technique: leap into action along the wire – Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon-style.

And not only that, but the Wirebug – veritable swiss-army knife of a mechanic that it is – does triple-purpose as a means to wrangle crippled monsters into a mountable state. Do enough Wirebug-related damage to a monster and you can initiate what the game calls Wyvern Riding. From atop the bucking behemoth, you can charge them into walls to damage them, or use their attacks to fight other monsters in the area. As cool as the territorial fights in Monster Hunter: World were, nothing beats using that alpha-predator display against them directly by forcing a wild Rathalos to reign fire onto your target.

This is just scratching the surface of Monster Hunter Rise. I haven’t even mentioned the gorgeous aesthetic inspired by feudal Japan, or the perhaps even more gorgeous soundtrack that’s paired with it. It’s still every bit as fun to hunt monsters, learn how to master each weapon class, and craft new equipment to dial-in your character build.

Iterating around a tried-and-tested formula like Monster Hunter shouldn’t be half as exciting as it is in Rise. But when your new ideas are this smart, and your core gameplay this good to begin with, well…Let’s just say it’s hard to argue with results that are this fun.

6. Resident Evil Village – Capcom

Resident Evil 7 was one hell of a pivot for the franchise. It traded in the RE4-era over-the-shoulder camera for a first-person perspective, traded in the globe-trotting scope of past entries for a more focused cabin-in-the-woods setting, and perhaps most importantly, it traded in the RE6 bombast of flying-a-fighter-jet-through-a-tunnel for the more lowkey action of fighting-a-dad-with-a-shovel-in-his-garage. All very smart moves indeed.

But for all its success, it left a pretty big question in its wake: “Where does the series go from here?”

Well, as it turns out, the answer was to take a page from the master himself: Resident Evil 4. Perhaps a few too many pages, but I’ll circle back to that a bit later. For the most part, Village is a sort of spiritual successor to RE4 combined with the new style of first-person gameplay that RE7 brought to the mix.

The key thing that made RE4 what it was, in my opinion, was the set-pieces. That game just had so many handcrafted, distinct scenes that would stick with you for a long time after you’d seen the credits. Village takes this idea to heart, going so far as to introduce you to its snow-dusted Romanian village of horrors in a direct homage to the RE4 town square fight. It’s an intense sequence – no sooner has the game introduced you to its basic enemies, bloodthirsty werewolves called Lycans, than it catapults you into an extended survival scenario with dozens of them. During my first playthrough, I barely knew what to do, and was borderline panicking as my ammo reserves hit zero. Of course, this is all carefully crafted to illicit exactly this type of response from the player, but it works so well that even though I knew exactly what it was referencing, it still ended up getting to me.

From there, the game introduces you to its main conceit: the village itself serves as a type of hub area that connects to the different domains of the game’s four central villains. Those areas are a castle, a mansion, a lake, and a factory (I swear I’ve heard this somewhere before…). I actually like this structure quite a bit, as each return trip to the village brings with it some new escalation to the combat as the sun gradually sets for the game’s finale.

Castle Dimitrescu is an early game highlight, as it introduces the game’s most memorable antagonist – the nine foot tall vampire countess, Lady Dimitrescu. Accompanied by her three much more reasonably proportioned daughters, she stalks Ethan throughout much of her castle’s various chambers and dungeon corridors. It never quite reaches the level of Mr. X’s oppressive presence in the RE2 remake, but feels more comparable to Jack Baker in RE7’s early hours. You might round a corner only to be suddenly greeted by her imposing stature and giant – err, giant-ness. Her entire sequence is so well-paced, and the voice talent behind her and her daughters is so good that you almost look forward to them suddenly appearing and scaring the shit out of you.

The other areas are also quite solid. The reservoir level introduces Moreau, the actual meme character for RE Village fans in the know, and who is indisputably the best. Then there’s the factory sequence, AKA where everyone gets lost. This level is full of the game’s most difficult enemies to deal with and is where the script really starts to flex its cheesiest, “boulder-punch” type of material. It’s a wild ride, and while it’s probably the weakest area in the game, it still runs circles around the RE4 factory chapters, sorry to say.

But it’s the game’s 2nd area, House Beneviento, that makes the biggest impression of all. Coming totally out of left-field, this area strips the player of their weapons and inventory and places them into what is essentially an extended escape room sequence. The more puzzles you solve, however, the more and more sinister feeling you start to get about this whole house. I don’t want to spoil what happens, but let’s just say that the climax of the level has more in common with Silent Hill, or Kojima’s P.T., than it does with typical Resident Evil horror. It’s one of the most memorable gaming moments of 2021, and definitely the year’s scariest.

Oh, and I have to throw in one extremely nerdy piece of Resident Evil history here. The other areas each have obvious RE4 parallels, whereas House Beneviento does not. OR SO YOU MIGHT THINK! The real-heads among you will realize that this area is, in fact, a callback to an early prototype version of RE4 that was later scrapped. Some people now call this prototype Resident Evil 3.5, and it featured Leon Kennedy exploring a haunted mansion, complete with evil dolls that would attack him. This is perhaps the best example of how deep Village’s reverence for RE4 goes. It’s such a subtle, fucking cool detail, and the fact that they turned a cancelled game into one of Village’s best levels – genius.

Resident Evil Village errs, at times, a bit too close to its RE4 big brother, but the roller coaster ride it creates from all its reimagining is difficult to argue against. The game might not be as inspired or as scary as Resident Evil 7 was, but it wins a lot of points with me for being a wilder, more risk-taking sequel with significantly improved combat and cheesiness that is just silly enough without going overboard. Ethan’s story, which I had assumed would be a one-off at the end of RE7, continues to be one of the best things the RE team has come up with in quite a long time. And while I won’t spoil the ending of Village here, I will say, that not only is its final hour cool as fuck, but it also leaves me once again wondering the same thing as before: “Where does the series go from here?”

I think the fact that I have no earthly clue gives me pause. But, at the same time, it’s damned exciting.

5. Inscryption – Daniel Mullins Games

What if I told you that the best indie game of the entire year was a card game? Yeah, I wouldn’t have believed me either. But Inscryption isn’t like Hearthstone or Gwent, or any other card game for that matter. It uses card game mechanics as the basic gameplay thrust, but there’s so much more going on here. It’s a card game in the way that Fez was a platformer, or The Witness was a game about solving line puzzles. Peel back its layers, and Inscryption is every bit the head-trip that those games were.

At the onset of Inscryption, you find yourself seated across from a face obscured by shadow, with only the yellow glow of its hypnotic spiral eyes punctuating the darkness. This face belongs to Leshy, the game’s main antagonist. You’re trapped in a cabin with him and forced to play his card game. At any point, you can try getting up from the card table and begin walking around, but you’re still locked in. There are various escape room-style puzzles throughout the cabin – cuckoo clocks expecting a certain time to be set, padlocked cabinets, that sort of thing. None of them have clear answers at first, so you challenge Leshy, get as far as you can, but inevitably, you will eventually lose. Turns out, this is one of those “die in the game, die in real life” type situations you’ve got going on with Leshy, so he harvests your soul. Huge RIP.

Each time you die, Leshy steals your soul with the flash of a polaroid camera, sealing you inside a card. This is one of the rogue-lite elements of the game, as you get to pass on traits from various cards from your deck into this “deathcard”, and that card will be added to the loot table of obtainable cards in subsequent runs.

The beauty of Inscryption, and a big part of its fun, is the multitude of ways it allows for the player to completely break the game. Those deathcards that I mentioned are one of the first methods for doing so. In my playthrough, I created a deathcard that had the stats of a Grizzly (4 attack, 6 health), the sacrifice cost of a pelt (0 cost to summon), and the sigil of a Mantis God (called Trifurcated Strike, it allows a card to attack three lanes at once). In no way could this card be considered balanced at all. And while I didn’t actually come across it until several runs later, as soon as I added it to my deck, I used it to wreck every boss and easily reach the end of Act 1.

Apart from this, I’ve also seen other players do really filthy strats with the totems, which are game’s passive buffs, in order to give their squirrels a sacrifice value of 3 instead of the usual 1. At that point, you can start playing some of the strongest cards in your deck in a single turn, which Leshy really has no way of dealing with. As much as I appreciate tightly balanced game mechanics and a fair challenge, there’s something extremely refreshing about a game that just removes those shackles and allows the player to go absolutely nuts.

It’s after Act 1 that the game really starts to reveal its true nature. Past this point, the game becomes a furious amalgamation of live-action FMV footage, graphical and sub-genre changeups, and fourth wall breaking interjections. I don’t want to give too much of the specifics away, but each of the game’s three Acts reset the gameplay – introducing a completely new ruleset while still riffing on the concepts you’ve learned before – forcing you to adapt and readjust your strategies, all before you figure out how to break the game yet again. It’s a very satisfying loop, and while I still think that Act 1 is the strongest part of the whole game, there’s something to be said for how Inscryption is never content with letting a single idea sit around long enough to get stale. It’s constantly on the move, searching for new things to throw at the player.

Inscryption is a game unlike any I’ve seen. It was certainly one of the biggest surprises of the year for me. I was shocked at how hard it was to put down, and how satisfying its card game was to master. The lo-fi art style and grotesque atmosphere were just the cherry on top. And yeah, your mileage may vary with Inscryption’s weird, meta story elements. For me, it was shocking, but not something I got a whole lot out of. What worked a lot more for me were the exceptionally creative boss fights, including some in the game’s third act that feel straight of the Hideo Kojima or Yoko Taro playbook.

Inscryption is unapologetically its own thing – equal parts weird, creepy, and funny – and it never stopped surprising me over the 12 or so hours I spent with it. The creativity at work here feels effortless, and that’s perhaps the highest praise I can give. It absolutely deserves your attention.

4. Returnal – Housemarque

I’ve got to be honest, the elevator pitch for Returnal sounds like the kind of thing you come up with when you have cocaine brain – somewhere between your idea for a blockchain startup and selling Hentai NFTs to the guys on r/wallstreetbets.

It’s like, a Rogue-like, with level design like Metroid Prime, the protagonist is like Ridley in Alien, but the monsters are all Lovecraftian and shit dude. Oh, and did I mention it was a fucking bullet hell? Shit’s like Ikaruga, my dude. Sensory-motherfuckin-overload.

On paper, it sounds like a shit idea – a mashup of random stuff that some guy thought was cool. In practice, however, Returnal is so ingenious that I wonder why no one has tried it sooner.

In Returnal, you play as Selene Vassos, a deep space scout working for the ASTRA Corporation. You are following a mysterious signal called “White Shadow” and trace it to a planet called Atropos. Disobeying orders, you attempt to land on the planet, only to crash land in the process. As you wake from the crash and begin searching for the signal’s origin point, you come across the deceased body of another ASTRA scout. Inspecting the body closer, you realize in horror that the dead scout is actually you.

You didn’t just crash land. You’ve actually been here for…years? The game’s story is entirely conveyed by audio logs that you discover, but the thing is, they’re all left by you – or rather, different iterations of you. Some of the logs are left by Selenes that have been battle-hardened over long stretches of time on the planet while other logs are the ravings of a lunatic, a Selene who’s completely lost her mind. It’s an eerie atmosphere to set a time-looping rogue-like in, and one that only gets more cosmically sinister the further you press forward.

It’s a really cool narrative that kept me engaged the whole way through, and honestly represents a nice complement to my GOTY from 2020, Hades. If Hades’ characters were the story thread pulling you through their Rogue-like, Returnal found a way to do it with a single character and a mysterious sci-fi concept. And not only that, but let’s give Returnal some props for representation: a female lead in an action game who isn’t in her 20s? Practically unheard of. Selene is a great character with an excellent performance to match.

I really love how difficult Returnal can get; the game is, at times, completely unforgiving. You can have an entire hour of gameplay end with virtually nothing to show for it on your next run. You can get 3 hours deep into a glorious, I-think-I’ve-got-this hot streak, only to have a boss absolutely humble your ass. You might think you have a completely broken build, only to encounter the one enemy that reveals your Achilles heel to you in a matter of seconds. If that sounds infuriating to you, then player beware. Returnal will only let you stop a run by setting the console to sleep mode, a design choice that’s shockingly hardcore for how lengthy the game can get when played carefully.

And trust me, you’re going to want to play carefully. One of the things I like most about Returnal is how punishing taking a single hit of damage is. Not only is health an extraordinarily precious commodity in the game, but every time you get hit, the game resets your Adrenaline Meter. Adrenaline is the game’s way of rewarding you for avoiding damage, and provides some pretty significant buffs, making it easier to reload, spot enemies, and even acquire the game’s currency. You really want to spend as much time as possible dodging and weaving your way through the neon bullet hell that the enemies blanket the map with.

Returnal is the first great game I’ve played that is truly “next-gen” only (it’s only on PS5 at the time I’m writing this). And sure, maybe some stripped-down, 30 frames-per-second version of this game with less particles on-screen could have been possible on current-gen hardware, but I think this game’s artistic vision, gameplay fluidity, and hard-but-fair difficulty are all made much better by not compromising. To me, it is the true demonstration of what is going to be possible on new hardware in the years to come.

Rachet & Clank: Rift Apart is a tech demo. Returnal is an experience.

3. Halo Infinite – 343 Industries

I’ve got a lot to say about Halo Infinite, the game I probably played the most of in 2021. So, introductions be damned, let’s get into it.

Let’s start with Halo Infinite’s campaign. You know, the paid add-on for the free-to-play multiplayer that only like 10% of the total audience has even purchased. Well, more people should try it, because it’s actually a ton of fun. Infinite makes the wise choice to brush aside the convoluted and frankly boring story of Halo 5 and does something of a soft reset to the 343 trilogy. You can tell they really wanted to get back to basics, going so far as to use Halo CE’s 2nd level – simply titled Halo – as their primary source of environmental inspiration, as well as doing away with the entire Cortana character in favor of a younger, newer AI known only as The Weapon – coincidentally also voiced by Jen Taylor (hmm).

Admittedly, the story is a bit dry in Infinite, but what it lacks in any kind of plot momentum, it makes up for with in some great character work for Master Chief, The Weapon, and The Pilot – the mystery man who salvages Chief’s half-dead body from the vacuum of space. So yes, the game might hate giving its characters their own names (I don’t know why), but there’s some solid writing here that got me to really care about the game’s main cast. That, plus the soundtrack, now jointly composed by Gareth Coker, Joel Corelitz, and Curtis Schweitzer is far and away the most powerful and evocative of that “Halo sound” since the days Marty O’Donnell and Mike Salvatori were still involved. Just listen to the tracks “Gbraakon Escape”, “Through the Trees”, “Adjutant Resolution”, or “Know My Legend”, and if you don’t feel a little tingle go up your spine, then I don’t know what tell you – you must be dead inside. These two elements together re-establish the much-needed emotion that Halo has been sorely lacking in its campaigns since the end of the Bungie era. There are moments of grandeur, beauty, and comradery in this campaign’s whole vibe that harken back to what Halo was at its core – and what differentiated it from just any other shooter story mode. You really get the sense that 343 Industries, somewhere in the long process of making this game, rediscovered a passion for Halo and what it meant to a lot of people back in those halcyon days of the original Xbox.

Okay, but enough with the bleeding-heart stuff, let’s talk about the dry mechanical details of why Halo Infinite is the best Halo we’ve seen in a long while. Gameplay is where Infinite absolutely and positively shines.

The weapon pool has been dramatically overhauled, and to phenomenal effect. For the first time since 343 Industries took up the Halo mantle – hell, I’ll say it, for the first time since Halo 3 – the oft-discussed Halo “sandbox” is a leaner, less redundant, and overall more rewarding playground for players to experiment with. Gone are the days of Halo 4 and 5, where three or four faction-specific weapons all served as variations on a single theme (think Battle Rifle, DMR, Covenant Carbine, and Light Rifle), and instead are replaced with weapon niches that might sound similar on paper, but actually occupy very different use-cases.

A great example of this new dynamic can be found with the newly revamped human shotgun, and its cousin, the Heatwave. While both of these guns fire clusters of projectiles and excel at close range, the Heatwave sets itself apart by its rather unique toggleable firing modes and ability to ricochet projectiles off of surfaces. As such, it’s a much more versatile weapon than you’d think at first glance. Sure, it can certainly come in clutch as a CQB weapon when you need it to be, but it can also do double-duty as a wide area-denial tool. Effective users can bounce the projectiles around corners to finish off stragglers or give would-be run-and-gunners pause about rushing in.

I think it’s this sort of dynamic – at work across the entire revamped sandbox – that gives Infinite that classic Halo feeling the everyone almost immediately feels when they get their hands on it. Turns out it wasn’t dual-wielding or sprinting or health packs that defined what classic Halo was. It’s the sandbox, stupid. And that makes a lot of sense, if you think back to the original Halo CE, and how different the human pistol was from the plasma pistol, or the assault rifle from the plasma rifle, and how little overlap there actually was between the way those guns worked. The newly focused sandbox of Infinite feels remarkably true to the series’ roots.

And to top this off, this is the first Halo I’ve played in a long while where nearly everything feels viable – including the fresh-out-of-spawn starter weapons. In normal Arena matches, you’re going to spawn with the MA40 Assault Rifle, Sidekick pistol, and 2 frag grenades. And honestly, this is a flexible enough kit to do just about anything you need. The assault rifle is easily the best it has ever been in Halo – capable of shredding an enemy Spartan from full health to dead in about half a magazine, and with decent accuracy to boot – and the pistol really toes the razor edge of being as overpowered as it was Halo CE or Halo 5, but with just enough reticule bloom to keep things in check. Even the BR75 Battle Rifle, the absolute gold-standard, “when you absolutely, positively got to kill every motherfucker in the room” gun of Halo, is tuned such that while it completely annihilates at mid-range, it’s time-to-kill is dialed-in such that, at near range, that same assault rifle or pistol will have the upper hand. It’s genius stuff – revelatory for a player like me who always thought that Halo never could quite get its shit together in balancing AR, pistol, and BR all in one game. To me, this is the first time where it feels like, shit, they finally nailed it.

And I haven’t even gotten around to the game’s equipment yet, which are map-pickup active abilities straight out of the Halo 3 playbook. And while I miss the Ol’ Faithful bubble shield, the collection in Infinite is way more interesting than it ever was in 3 – scandalous statement, I know. The Grappleshot is the undisputed highlight, and has more use-cases than you can imagine. It can grant you speed boosts around the map, give you lots of vertical shortcuts, it can be your escape plan, your vehicle hijacking tool, and even your energy sword’s best friend. Other equipment, like the Repulsor or the Drop Wall, have some pretty shocking sandbox interactions that I’m still learning about, dozens of hours later. The equipment is like the spice of the Halo Infinite soup: they provide just the right amount of extra variables to the formula for you to get some really wild, really hilarious moments out of it.

But Infinite is not a perfect game, of course. It has the requisite bugginess that is to be expected of just about every modern AAA game release (sigh). The open world of the campaign, while extremely fun from the perspective of the Halo sandbox, is peppered with a lot of uninspired map markers to check off and bland audio diaries to find. And the tradeoff in going with a single open world for the campaign means there’s significantly less environmental variety than prior Halos. And even the more linear sections that make up the back half of the game, while well designed from a combat perspective, are all seemingly made up of the same couple dozen Forerunner chambers and hallways. It can get really repetitive at times. Then there’s the vehicle physics, which are perhaps the most frustrating in the franchise’s long history. Just try flipping a vehicle or driving the Brute Chopper for any period of time and you’ll see what I mean. Oh, and the final phase of the last boss fight feels hand-tuned to make you never want to play the game again. It manages to end an otherwise very solid campaign on a very sour note. But I digress…

It’s been 6 long years since 343’s last Halo. It’s been 11 longer years since a Halo release that I really cared about. And 14 since one that I could truly profess my love for. It’s been a long time coming, but you don’t get greatness overnight, I suppose. Halo Infinite is the rare sequel that feels worth the wait.

Infinite reasserts the timelessness of Halo’s gameplay. Its campaign, at its best, recaptures some of that lightning in a bottle that was The Silent Cartographer. It’s multiplayer, as confident as it has been since the Halo 3 era, reminds why arena shooters were so beloved to begin with. All the groundwork has been laid here. Now, if 343 Industries can nail their post-launch support of the game, I could easily be coming back to Halo Infinite for years to come. With a game as strong as this, there’s hope.

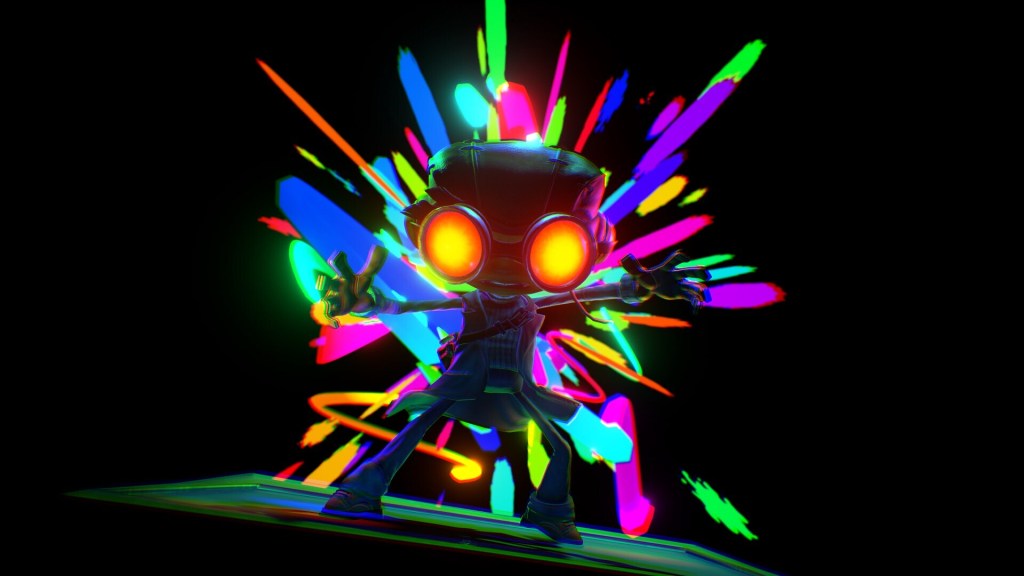

2. Psychonauts 2 – Double Fine

The original Psychonauts was such a perfect debut for Double Fine as a studio. Embodied in the summer camp of adolescent psychics was Double Fine’s own quirky sensibilities and their passion for creating new and ambitious game worlds. And underneath all of that was an angst, the kind of edgy attitude that could have only come from a young, scrappy startup with something to prove.

Psychonauts 2, by contrast, is separated from that Double Fine by 16 years. The designers, artists, and Tim Schafer himself are older now – many of them parents. As such, the focal point of the long-awaited sequel are not precocious preteens, but rather a group of old souls – the retired founders of the Psychonauts themselves. It’s these minds that Raz dives into throughout the course of his second odyssey of astral projection. Inside, he finds the sorts of emotional baggage you might associate with the ravages of time – regrets, grief, trauma, even dementia and alcoholism. Psychonauts 2 approaches all this subject matter with a sense of empathy, and a desire to use its visual language in order to promote understanding and healing. And it manages to do all this while still bursting at the seams with the creative energy and whip-smart humor that the first game was so beloved for.

The first thing that everyone thinks about when they think of Psychonauts is the art style. The comparison I see a lot of people draw is to the director Tim Burton – presumably for his film A Nightmare Before Christmas – but that analogy really doesn’t do it justice. Psychonauts draws inspiration from a whole array of sources, yet it has a visual language all its own – there really is nothing else like it. Psychonauts 2 does an amazing job in uplifting that style into the modern era, complete with HD textures, modern lighting techniques, etc. For me, it’s one of the most beautiful games of the year, hands down.

The other thing that everyone thinks about when they think of Psychonauts is the levels. Specifically, the levels that take place inside the minds of other characters. Psychonauts 2 has an incredible collection of these, with so much creativity and detail throughout all of them that I still find myself thinking about many of them, even now. A great early game example is a hybrid level that is one part hospital one part casino. If that mashup sounds nonsensical to you, well, it did to me too. That is, until you see it in action, at which point you can’t help but marvel at the ways Double Fine found to stitch these ostensibly incompatible ideas together. At one point, Raz places bets on which playing card suit – spade, club, diamond or heart – will win a sort of 2D horse race, running and jumping along the lines of a cardiogram machine. At another point, you enter the hospital’s Maternity Ward, where various characters are gambling on a giant roulette wheel, trying to win its most coveted prize: a baby.

Later, in one of my favorite levels in the game, Psychonauts 2 has you competing in a TV cooking competition, trying to impress a panel of goat judges. They give you a time limit and a series of instructions, and you as Raz must race around the arena to prepare all the ingredients the way they’ve been requested. No matter whether you succeed or not, the goat judges never failed to make me laugh.

But perhaps the most interesting, most high-concept level idea in the game belongs to a character called PSI King. Voiced by Jack Black in an excellent performance, the PSI King is a character who, when you first encounter him, has existed only as a brain in a jar for years. Over that long span of time, he’s lost the use of his five senses. When you first enter his mind, it is a dark void, and his voice is only a tiny orb of light. But over the course of the level, you as Raz help him recover his sight, touch, taste, smell, and hearing. The ensuing journey to recover his senses quickly turns into a 1960s psychedelic trip, complete with oversaturated tie-dye throughout all the textures, sitar chords playing throughout the soundtrack, and a Mystery Machine-style tour bus. To cap off the whole wonderful thing, the finale has Jack Black performing an awesome rock song in the way that only he can. It’s hands down one of the best sequences of the year.

All of this imaginative design is backed up by Tim Schafer’s own dialog for the game, as well as his very particular brand of humor. It was so refreshing, especially in 2021, to play a game that could actually get me laughing out loud, and that didn’t just rely on the Joss Whedon-style quirky nerd-banter that has seemingly infected everything as a stand-in for comedic talent. Psychonauts 2 plays around with numerous types of punchlines, and embeds them everywhere in its game world. Some of the funniest stuff in the whole game can only be found by backtracking and talking to the same NPCs repeatedly. It makes you really want to take your time with the game and really soak it all in. Tim Schafer is every bit the creative genius that people say he is, and I daresay that Psychonauts 2 might be the best thing he’s written to date.

I don’t know if Psychonauts 2 could have ever really hoped to live up to the original game’s one-of-a-kind stroke of genius. That game really does deserve its status as one of the all-time greats. But I do know this: I could not have hoped for a better sequel than what we got with Psychonauts 2. Tim Schafer and the gang might have gotten up there in years since they first envisioned Raz, but that clearly hasn’t slowed them down a bit. Double Fine have really outdone themselves here, creating what is undoubtedly their best game in years.

1. Deathloop – Arkane Studios

The last time I encountered Julianna in Karl’s Bay, she killed my ass with a machete. This time though…this loop, I’m ready for her.

This new Julianna had been taking potshots at me earlier from the rooftops. Now, unbeknownst to her, I’m cloaked and slowly making my way up there in an attempt to jump her. I get to her former perch, but she’s nowhere to be seen.

I stay cloaked, not moving at all and look around anxiously. I check behind myself, half thinking she’ll be there, machete in tow. But no, not there. Instead, I spot her running around down on street level. Funny, we’ve switched places, I think.

She’s running to and fro, impatiently searching for me, ready to wrap things up this shit up. I watch for a little while, debating what I should do, when I see her run through the boat shack down by the beach. Oh, I think to myself. You just fucked up.

See, I’ve played this level enough times now to know that the area past that boat shack is a dead end. Assuming she also knows that, she was probably hoping I would be hiding back there, and she could box me in. Instead, I have the high ground now, along with a front-row seat to her funeral. It’s now or never, I think, and I begin throwing every remote mine I have in my inventory. My throws are pretty good, and I manage to land them all in a neat little pile right outside the boat house doors.

Not twenty seconds later, right on schedule, she’s back from exploring the dead end. But then, just a dozen feet or so from the remote mine heap, she stops dead in her tracks.

Fuck. She knows something’s up. It’s just then I remember that the remote mines make a steady beeping noise when they’re armed. Shit, she fucking heard them. I’m starting to panic, trying to quickly pull a new plan out of my ass.

And just then, as if shrugging off her suspicions, she starts running again. Dead ahead, and right over top of the mines – she practically trips over the pile.

In disbelief, but without hesitation, I pull the detonator. The next millisecond, she’s blasted sky high. It’s an insta-kill. Back in real life, I practically jump out of my chair. Got your fucking ass.

This is the cat and mouse game at the core of Deathloop, the latest game from the developers at Arkane. While the game is primarily a PvE single player experience, it has an online mode where other players can invade your world as Julianna. When doing this, their only goal is to kill you. You, on the other hand, have all the AI enemies to contend with, objectives to complete, and the risk that, if you die, you’ll lose all the progress you’ve made for that loop. You’ll reset back at the beginning of that day, having lost just about everything. And it all starts over.

You don’t have to play Deathloop online, with open PvP enabled. It’s real simple to turn off and get a much less deadly AI Julianna instead. I turned it on though, and left it on for the entirety of my 30 or so hours with the game. And the result was some of the most tense, white-knuckle multiplayer stealth action I’ve experienced since wayyy back in the days of Splinter Cell Chaos Theory Spies vs Mercenaries. I’ve got a lot more stories than just the one I recounted above.

Underlying all this is the game’s central concept: You are Colt Vahn. Every morning, you wake up on an empty beach on Blackreef island. A young woman named Julianna Blake, as well as every masked goon on the entire island, wants you dead. If they kill you, then you’ll wake back up on the beach – its morning again. If you manage to make it to nightfall, surviving to the end of the day, same thing – you loop back to the beach. Your goal is to figure out why this is happening, explore the strange island of Blackreef, and hopefully break the loop so that you can escape the Groundhog-Day-from-hell you are trapped in.

The game contains just four levels for you to visit: Updaam, The Complex, Fristad Rock, and Karl’s Bay. Picture each of these maps as giant, wide-open Dishonored levels – each has multiple entrances and exits, their own assassination targets in the form of what the game calls Visionaries, and tons of optional paths and secret areas to explore. With a couple exceptions, each map also has 4 iterations, based on time of day you visit it – morning, noon, afternoon or evening. Visit Updaam in the morning, and you’ll find that things are pretty low-key. Lower level enemies patrol the streets, and there’s no Visionaries present on the map. Visit it in the evening, however, and you’ll be greeted by much higher level enemies, many more of them, as well as an entire party going on at the mansion belonging to scumbag Visionary Aleksis Dorsey, complete with its own fireworks show. Some maps will get snowfall as the day progresses. Others will have new paths open up while others close themselves off to you.

It can be overwhelming trying to figure the maps out during your first few loops, but over the course of the game, you’ll become intimately familiar with every nook and cranny of these elaborate murder playgrounds. Part of the beauty of Deathloop is that, by the late game, you’ll practically be speedrunning each map: enter fast, leaping from roof to roof, headed straight for an objective, completing it, and fucking right on off out of there. Colt’s ho-hum attitude as he repeats these things really endeared me to him, and it feels paced out really well so that you as the player are aligned with his emotional state as you figure things out for yourself. Call it ludonarrative consistency if you want to be academic about it – it’s just good storytelling.

Deathloop’s gameplay concepts can be difficult to wrap your head around at first, but the game does an excellent job of slowly easing you into it. It’s not often these days that I brag on a game’s tutorializing, but Deathloop integrates it so seamlessly into the early parts of the story that I felt it deserves a shoutout. Without it, this game could have been so much more obtuse and frustrating. As it stands, just about everyone seems to figure it out pretty easily.

Another big highlight of Deathloop are the Visionaries themselves – eight of the island’s most important scientists, artists, and trust fund babies. The “big puzzle” of Deathloop is figuring out how to kill all eight of them. Not too big of a problem, except that there isn’t enough time in the day to kill them all before the island loops and they all come back to life. Many of them have overlapping schedules such that you can only murder one and not the other. So, you end up having to find creative ways schedule your target’s demise, such that you don’t even have to be there for the kill confirm. Or you learn their feelings about one another and manipulate them such that they might show up somewhere else later in the day to confront another Visionary. I don’t want to spoil any of the specifics directly, but orchestrating the final, “perfect” run of Deathloop is a really satisfying journey. Not to mention, the characterizations of the Visionaries themselves are really fun. They’re extraordinarily campy characters, but each of them are different enough from one another, with enough eccentricities and hate-able qualities to stick out in your memory.

There’s so much about Deathloop’s whole vibe that I absolutely love. The art style is perhaps my favorite of the entire year – it pulls from such a wide array of cult cinema sources, from Sean Connery-era James Bond films to 1970s Grindhouse and Blaxploitation cinema. The entire island of Blackreef has this hard-to-put-your-finger-on bohemian quality to it, complete with the type of color palette you might associate with 1960s psychedelic pop art. And, of course, the tone of the whole thing – the glee it has for violent delights as well as the humor and wit embedded in its people-don’t-really-talk-like-this character dialog – shows a very obvious love for the films of Quentin Tarantino. Combine all of these influences with the game’s 1960s style spy movie soundtrack, and you’ve got a recipe for a game world that has such a distinct sense of self, that’s it becomes intoxicating just to be a part of it. For me, this is the most fully realized and fascinating fictional universe Arkane has ever produced, and it’s not even close.

I’ll admit that some of my intense love for Deathloop may have been a time and a place thing. A “you had to be there” sort of thing. Because, without the extra spiciness that those human-controlled Juliannas provided for me, the game might not have hit quite as hard as it did. And I’m not sure whether or not the experience I had is even still possible. There’s nowhere near as many people playing now as there were during launch week, when I was dumping loads of hours into the game. It’s possible my experience may have been a fleeting, ephemeral sort of thing.

But there’s no denying how awesome it was. Or how obsessed with this game I was for a period of a couple weeks. Or how much I enjoyed playing as Julianna myself, ruining the loops of dozens of Colts. There was nothing quite like it.

Arkane has been one of the most consistently exciting yet criminally underrated developers of the last decade of gaming. They don’t really depend too much on sequels, and their various flavors of immersive sim games have been some of the best that have ever been created. Their 2017 game Prey is still a game I’m recommending to people, especially considering that apparently no one has actually played it.

With Deathloop, Arkane has gone from a “developer to watch” to simply one of my favorite developers period. Their whole portfolio is brilliant, and now they’ve made my favorite game of 2021.

This team just don’t miss.